Richard Williams in the trailer for Prologue

Canadian-British film artist Richard Williams died of cancer on August 16 at his home in Bristol, aged 86. He was — and this is not an exaggeration — the greatest animator in the world and had been for decades. Over the course of his career, he conjured unreal visions solely with pen and paper, resisting almost all use of computers (toward the end of his life, digital entered his process for the final compositing stage, but never for the actual animation). A notoriously exacting boss at his company, Richard Williams Animation, such attention to detail produced a singular style and beauty rarely matched and even more rarely exceeded in the form.

Williams got his start in commercials, eventually progressing to directing the half-hour children’s film The Little Island. He honed his craft working both on shorts and on title sequences for live-action films, crafting animated segments in movies like A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, The Charge of the Light Brigade, and several installments in the Pink Panther series. While these works demonstrate obvious skill and wit, it’s his 1971 adaptation of A Christmas Carol, which won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short, that first truly showcased how he approached the art on a level unlike any other animator.

Beyond the smooth movement, the visual style based on 19th-century engraved illustrations, the bold use of shadows, and the inventive transitions, Williams’s A Christmas Carol feels three-dimensional in a way unlike any television or theatrical animation of the time. (It was for this reason that the short, originally made for TV, was later shown in theaters.) The “camera” moves in a way that, for the most part, would not be seen widely until the advent of computer animation decades later. Traditional animation still almost never adopts this kind of approach, which means that works like this remain distinctive today. It’s this skill that made Williams an obvious choice when, in the late ’80s, director Robert Zemeckis was looking for someone to helm the animated elements of his unprecedented live-action/animated hybrid film Who Framed Roger Rabbit.

Williams not only ramped up his game with the larger budget but was also a big reason that the blending of reality and cartoon worked so well in the film. Tiny details, like ensuring that the eyelines matched between the real actors and their animated co-stars, sold the movie’s world, in which humans and toons live alongside one another. This is why it holds up so well, even as later, more “real”-looking CGI creations fail to age gracefully.

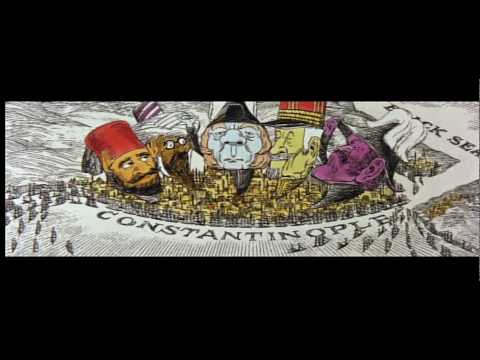

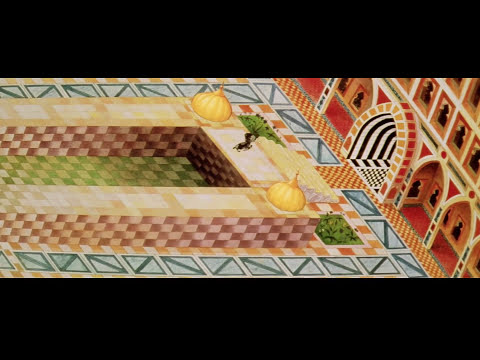

The success of Roger Rabbit gave Williams the clout he needed to acquire funding to finish his magnum opus. Since 1964, he had been working on and off on a project based on Middle Eastern folklore, managing to finish only around 20 minutes of footage. But now production of the film that would become known as The Thief and the Cobbler could commence in earnest. And what Williams and his team produced was nothing sort of astonishing:

Hugely complex sequences were all pulled off without the use of any computers. Again, you cannot find modern traditionally animated films that look this good. The dizzying use of pans, zooms, shifts, and movements we don’t technically have names for because they are literally impossible to do in live-action film make Thief a staggering visual accomplishment. Unfortunately, production ran badly over deadline and eventually led the bond company which insured the film to seize control of the production. The film was then recut, with new (vastly inferior) animated sequences inserted, including musical numbers. This version was released as The Princess and the Cobbler in 1993. Miramax Films then bought the American rights to the movie, whereupon they recut it yet again and released it as Arabian Knight in 1995. Both releases flopped.

Bootlegs of Williams’ workprint of Thief circulated for years among animation enthusiasts. Eventually, in 2006, fan Garrett Gilchrist combined several different sources to produce “The Recobbled Cut,” a restored version which hewed as closely to Williams’ original vision for the film as possible. One of the most impressive independent fan efforts ever undertaken, it helped introduce a new generation to both the brilliance of the original and the injustice that had been done to it. Williams’ own original version has now been preserved by AMPAS. While he was never able to see it fully completed in his lifetime, what he was able to complete is at least kept safe from being lost forever.

In his later years, Williams settled into a space as a guru of animation, with his 2001 book The Animator’s Survival Kit becoming a widely consulted resource on the art. While the desecration of Thief stymied his creative output, he still occasionally put out works to remind everyone of his prowess. In 2015, he released his short Prologue, a thrilling action sequence done entirely in pencil and again showing off his unmatched sense for movement and framing. It would be nominated for an Oscar. As the title suggests, it was meant to be the beginning of a larger venture, a feature film adaptation of Lysistrata. His death means that this is yet another unfinished project from Williams. While bittersweet, that also seems strangely fitting for him, as an artist whose refusal to settle meant he was forever blazing toward perfection. Given the structure of the animation business today, it seems unlikely we will ever see another like him.

Thanks so much for this article and kudos to everyone involved in the greatest animated film of all time, the Thief and the Cobbler (Recobbled Cut)…

Great article! This is why I subscribe to Hyper’s newsletter.