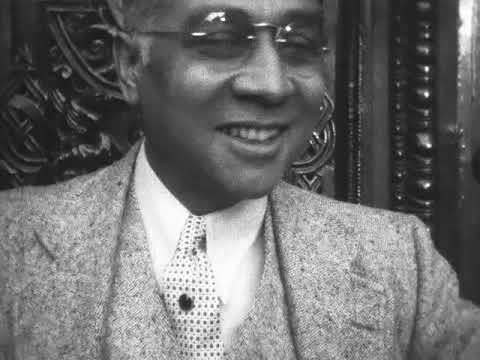

Henry Ossawa Tanner‘s canvases were mostly of far-off landscapes and expressive Biblical scenes. The 19th-century American artist, who began his career in Philadelphia and ultimately exhibited richly detailed canvases at the Paris Salon, left few visual crumbs to illustrate his own life. There was a sculpted bust of his father, portraits of his mother, and others of his wife and their son, Jesse. (Sometimes he snuck loved ones into his Biblical paintings by using them as models.) But for the most part, Tanner left himself out of his work. So his cameo in a recent documentary came as a precious surprise.

Myth of a Colorblind France is a survey of Black American artists who moved to Paris to live freer from racism, such as Josephine Baker, James Baldwin, and Beauford Delaney. Tanner appears ever so briefly, strolling with his niece Sadie in a clip from a home movie recorded in 1930. He laughs, mouths silent words, and tips his hat. He also eyes the camera suspiciously, a bit uncomfortable being the subject of its attention. Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander and her husband Raymond Pace Alexander brought along their 16mm camera to visit her Uncle Henry. You can watch the complete 15-minute reel of their footage via the Penn Archives.

Myth of a Colorblind France director Alan Govenar told Hyperallergic that “to have a small handheld movie camera was very special. The footage itself is truly remarkable.” It was also professionally edited, with intertitles noting the places and people who appear (like suffragist and civil rights activist Mary Church Terrel and composer Clarence Cameron White). “That, I would imagine, is very unusual for home movies for the period,” Penn archivist J.M. Duffin shared with Hyperallergic.

This trip was the last time Tanner and Sadie saw each other. She was born after he had made his permanent move to Paris in 1891, and they met during his occasional stateside trips. “[He] met us upon our arrival in Paris,” she recalled in a speech at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1970, on the occasion of a solo exhibition of Tanner’s artwork. “The day after our arrival, he took us to lunch at his favorite restaurant, a small, typically French family-operated business on the Left Bank catering mostly to artists.” It’s unclear whether this is the bistro that appears in the film.

At a time when Tanner’s colleagues were painting nightclubs, streetscapes, and each other, he kept the 20th century — and his experience of it — outside the frame. Seeing him as a dapper flesh-and-blood gentleman, quick to laugh with his hands in his pockets, adds a new dimension to him.

Raymond probably played cameraman most of the time, but “Some of it may have been shot by Tanner, because there is footage where Sadie is seen with Raymond,” Govenar notes. “I think they were enjoying using this camera.” And they clearly enjoyed each other’s company. In her speech, Sadie said her uncle encouraged her to visit again, but that other commitments and the births of her children got in the way. In fact, she was recovering from the delivery of her youngest daughter when she received a cable notifying her that Uncle Henry had died.

Myth of a Colorblind France is available in virtual cinemas.