Whitney Biennial 2014: Anthony Elms on the Second Floor

Whitney Biennial curator Anthony Elms took on the nebulous meaning of "American art" most directly in his selections, but the results don't really say a lot about what it means to be American — at least not in a way that makes it distinct from Canadian, Australian, Argentinean, or some other nationa

Whitney Biennial curator Anthony Elms took on the nebulous meaning of “American art” most directly in his selections, but the results don’t really say a lot about what it means to be American — at least not in a way that makes it distinct from Canadian, Australian, Argentinean, or some other national identity forged in the modern era by immigration, capitalism, environmental devastation, and a displacement of indigenous cultures. His characterization of America as “constant expansion” smacks of the absurdity of manifest destiny.

Elms also explores another theme — much more successfully, I believe — and that had to do with the notion of the museum, particularly the Whitney Museum, designed by Marcel Breuer in 1966. Elms quotes one of the architect’s notes on the building in his own curatorial statement for the biennial: “What should a museum look like, a museum in Manhattan?” The answer isn’t straightforward.

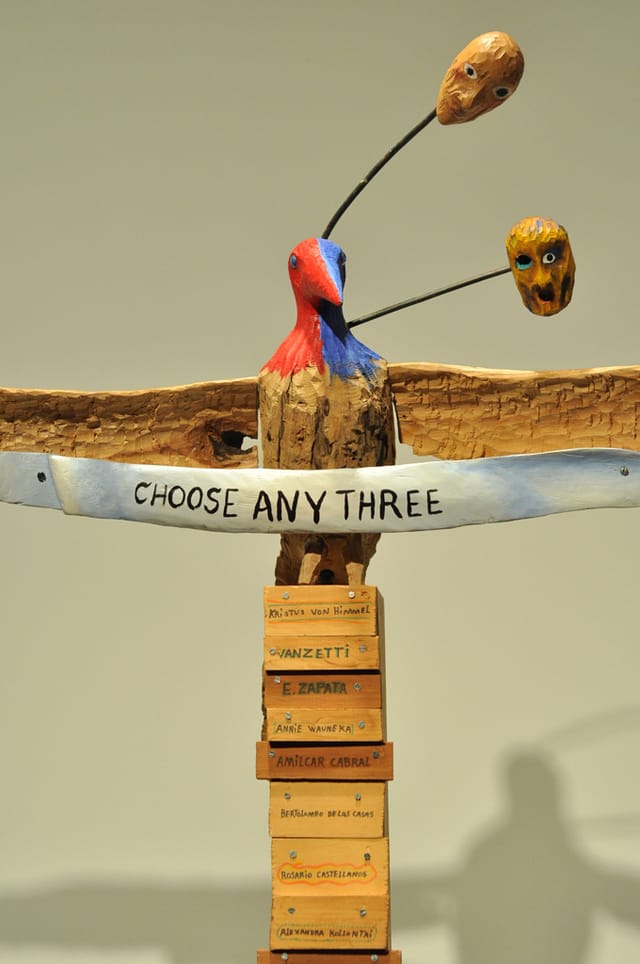

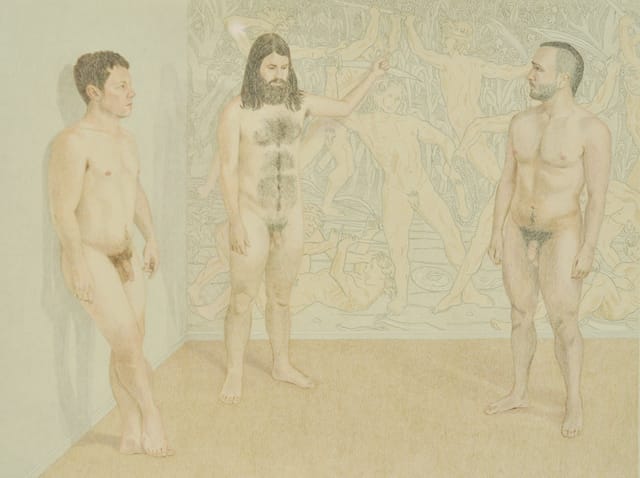

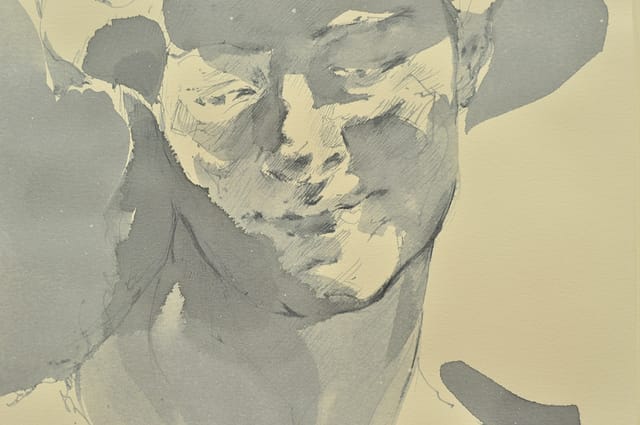

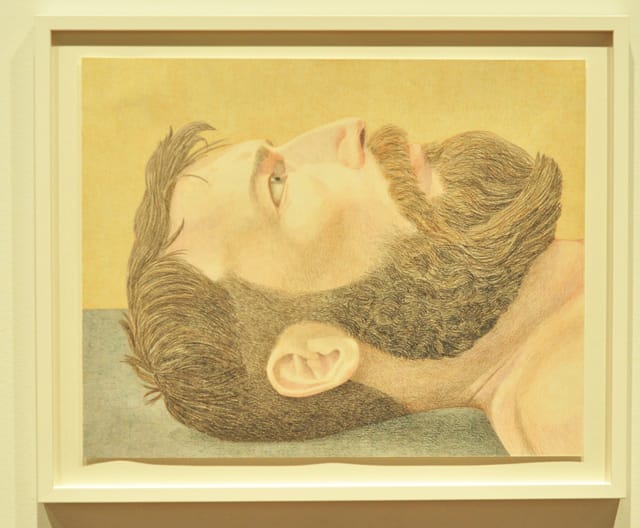

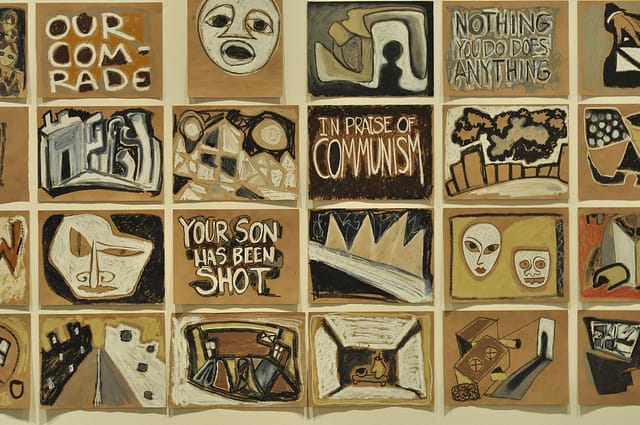

Elms chose 24 artists and groups for his part, and some soar, like Terry Adkins’s striking Aviarium works installed high near Breuer’s impressive gridded concrete ceiling. Others merely saunter, even trip, like Paul P.’s well-executed drawings that seem largely out of place in this show.

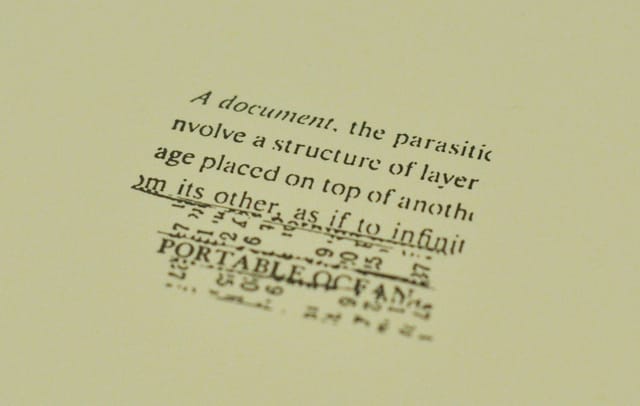

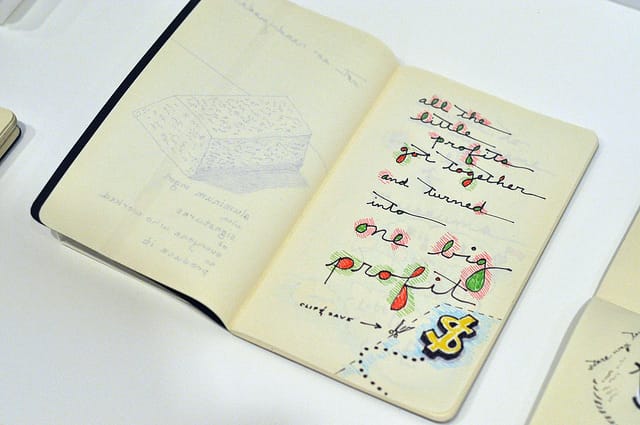

One aspect of Elms’s curatorial work that I really appreciated was his desire to fit in diminutive works like Susan Howe’s letterpress sheets, which captured some of the poetry the curator seemed eager to convey, and the drawings of Elijah Burgher, which were precise but ultimately lifeless — not all the small pieces fit well together.

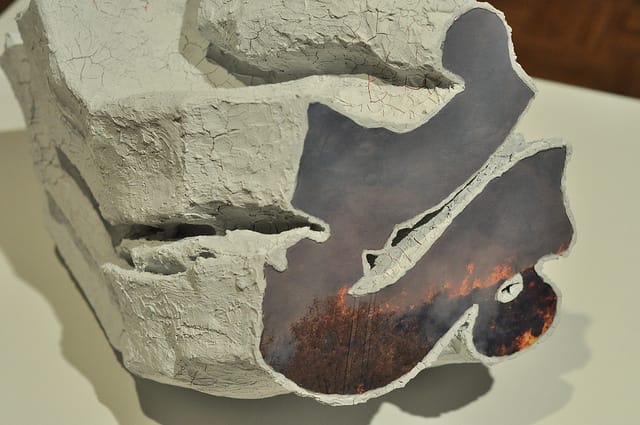

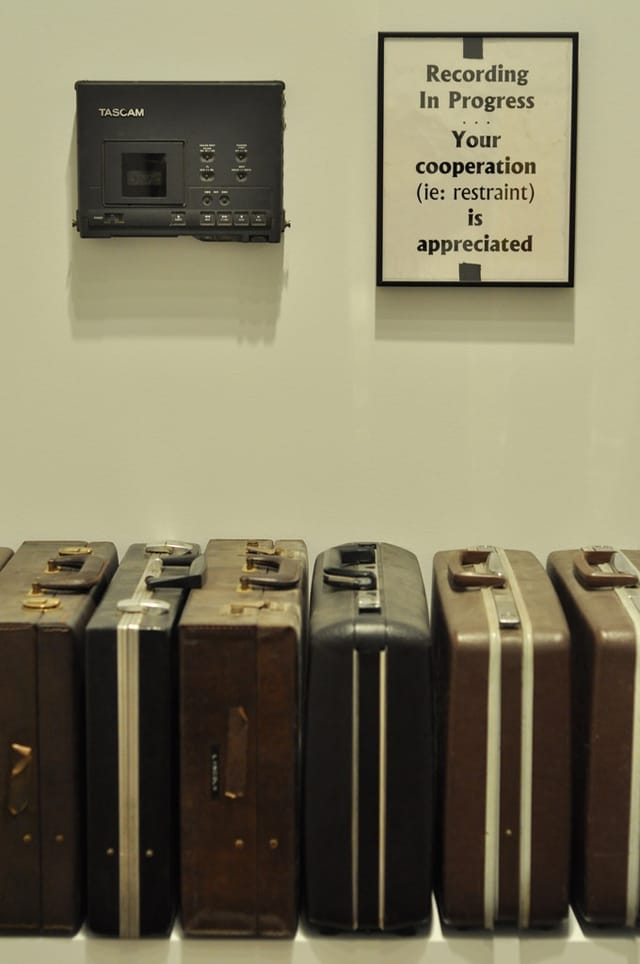

Elms’s exhibition suggests that the Manhattan museum is a great repository. Carol Jackson’s “Pandemonium” (2013) looked like it could’ve been as at home in the American Museum of Natural History as it was in a contemporary art space, and that ambiguity worked well. Public Collectors’ artifacts from the life of Malachi Ritscher were also a ponderous addition, chronicling a man’s passion for the ephemeral world of sound — he recorded more than 2,000 concerts in Chicago’s experimental scene. The fact that Ritscher ended his own life by setting himself on fire in front of Leonardo Nierman’s shiny “Flame of the Millennium” (2002) public sculpture adds a poignant dimension to his life’s work, which was to capture what may otherwise have been lost forever. Peter Margasak, writing in the Chicago Reader, mentioned that he once tried to interview Ritscher, but the activist declined, “saying he didn’t want publicity.” At the scene of the passionate antiwar protester’s self-immolation, the police found a video camera, a canister of gasoline, and a sign that read “Thou Shalt Not Kill.” This is the type of story that tests the limits of a Manhattan museum to fully contain its many facets.

Elms’s contributions to the Biennial seem to sprawl throughout the building more than the work of the other two curators. His placement of Charlemagne Palestine’s sound works in the stairs were absolutely perfect, as the sound reverberated off the cold stairs, though his inclusion of My Barbarian on the ground floor was a letdown, since their work was neither good nor insightful, and their props (or art, depending on your perspective) are pretty toothless.

We do have Elms to thank for one of the most interesting parts of the biennial, Zoe Leonard’s camera obscura on the fourth floor. This transformation, which could’ve easily felt like a goofy parlor trick, served as a fitting farewell to a building that refracted the world of American art for almost 50 years, helping to change its course at many points during that history — and what a history.

If the Whitney Biennial is supposed to capture the pulse of what’s happening in the American art world, or at least chronicle important slivers or pockets that are toiling away for the love of art, then this sprawling show — all three parts — largely failed. Judging from the exhibition, you’d think American culture was in retreat, but the opposite is the case in the age of the internet. There’s a strange timidness to this biennial that made it feel as manicured as a public garden, where things never get too wild, too dangerous, or too exciting. One thing is for sure — this isn’t the American art I’m seeing in the world today.

The 2014 Whitney Biennial opens Friday, March 7 at the Whitney Museum (945 Madison Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) and continues until May 25.