Generations of Indigenous Voices from New York State

What unites this patchwork exhibition is the land: The artists are all Native Americans whose ancestry is tied to the place now known as New York State.

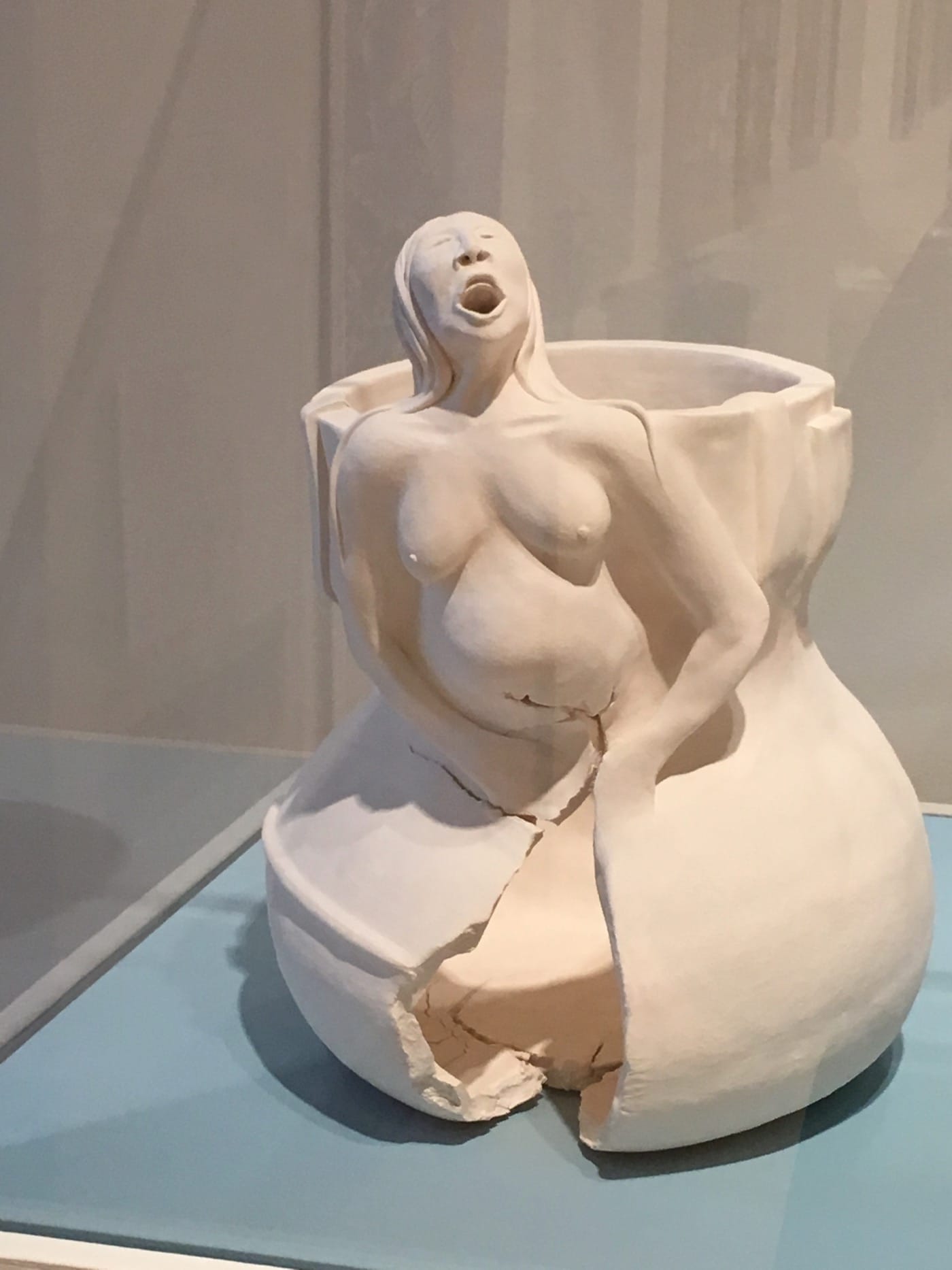

At the Samuel Dorsky Museum in New Paltz, New York, there is a spacious gallery filled with seemingly unrelated art. Realistic portraits hang next to paintings of mythical landscapes whose neon hues are unseen in nature. Photoshopped photography hovers above woven baskets that could have been braided centuries ago, and statues crafted from delicate clay are juxtaposed with sculpture fashioned from trash. What unites this patchwork exhibition is land. The artists are all Native Americans whose ancestry is tied to the place now known as New York State.

The exhibition Community and Continuity: Native American Art of New York is culled from the New York State Museum’s collection of contemporary Native American art. NYSM is known for its historical and archeological Indigenous objects, which number in the millions and range in date from 13,000 years ago to the early 20th century. But in 1996, the museum began acquiring works by living Algonquin and Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) artists to celebrate the continuing vibrancy of these communities.

It goes without saying that Indigenous artists are underrepresented in most mainstream art museum collections. When they are present, the work shown is rarely contemporary. But in the past ten years, the museum monolith has slowly shifted. The Portland Art Museum, the Denver Art Museum, and the Brooklyn Museum among many others, are making efforts to introduce living Native American artists like Teri Greeves, Wendy Red Star and Nicholas Galanin to their collections.

Still, it is refreshing – and exceptional – that Community and Continuity has 32 artists on view. Some, like Gail Tremblay (Mi’kmaq and Onondaga), have been on the arts scene for decades. Her pieces are visible coast to coast, in collections from the Smithsonian Institution in DC, to Microsoft’s headquarters in Seattle. For the work that appears in New Paltz, “Dreaming of Wild Foods” (2013), Tremblay looped red, 16 mm movie film into the shape of a basket, using traditional basket-weaving techniques. With a curl of green film on top, the cylindrical vessel looks like a strawberry. The basket is outwardly playful, but its scarlet film has darker implications. Called “Fishing at the Stone Weir” (1967), the movie on the film documents Netsilik Inuit demonstrating their fishing techniques. This might sound harmless, but according to Tremblay, the movie is presented in a manipulative manner — one that robs the subjects of their ability to represent themselves honestly. In response, Tremblay asserts some of her own power over the film; she twists and contorts the reel into shapes its creators never intended.

Along with seasoned artists, Community and Continuity showcases a handful of new faces, most notably Jeremy Dennis (Shinnecock) and Jay Havens (Six Nations Mohawk). Dennis’s contribution to the exhibition is a photograph from his series Nothing Happened Here (2016–present). His pictures capture people doing everyday activities — biking, walking, or simply standing — while arrows longer than arms protrude from their bodies, blood pooling around the holes. From a cursory glance, you might think the art is a commentary on the burden of being Native American in the United States or a reflection on how genocidal trauma is passed down from one generation to the next. But Dennis notes that the people in the portraits are not of Indigenous descent. In a lecture he gave at Suffolk County Community College, he explained that the arrows “portray the tension of knowing but trying to suppress the idea that we’re still here.” To create the illusion, Dennis had to hold up each arrow to the model as his camera, set on a timer, took the shots. He then erased himself from the pictures, becoming invisible yet impossible to ignore.

Near Dennis’s photograph, a grey-blue heron almost nine feet tall dangles from the ceiling. This slowly spinning bird, suspended by its beak, is immediately disturbing. The piece “The Bargain Hunted Heron” (2018) is made from 1,000 Walmart bags that are painted and braided together. Dreamcatchers sit where the heron’s heart would be. Havens created the work as he watched two giant malls spring up in Vancouver and displace the wildlife there.

One of the show’s greatest strengths is the wall texts, many of which the artists wrote. Instead of the curators explaining or directing the exhibition’s narrative, the artists speak for themselves. As a result, the exhibition isn’t always cohesive, but the show does what an art museum should: it provides a place for a variety of voices to be heard.

Community and Continuity: Native American Art of New York continues at the Samuel Dorsky Museum (on the campus of the State University of New York at New Paltz, 1 Hawk Drive, New Paltz, NY) through December 9. The exhibition was curated by John Hart and Gwendolyn Saul.