"All Lives Are Black Lives": Examining Race in South Africa

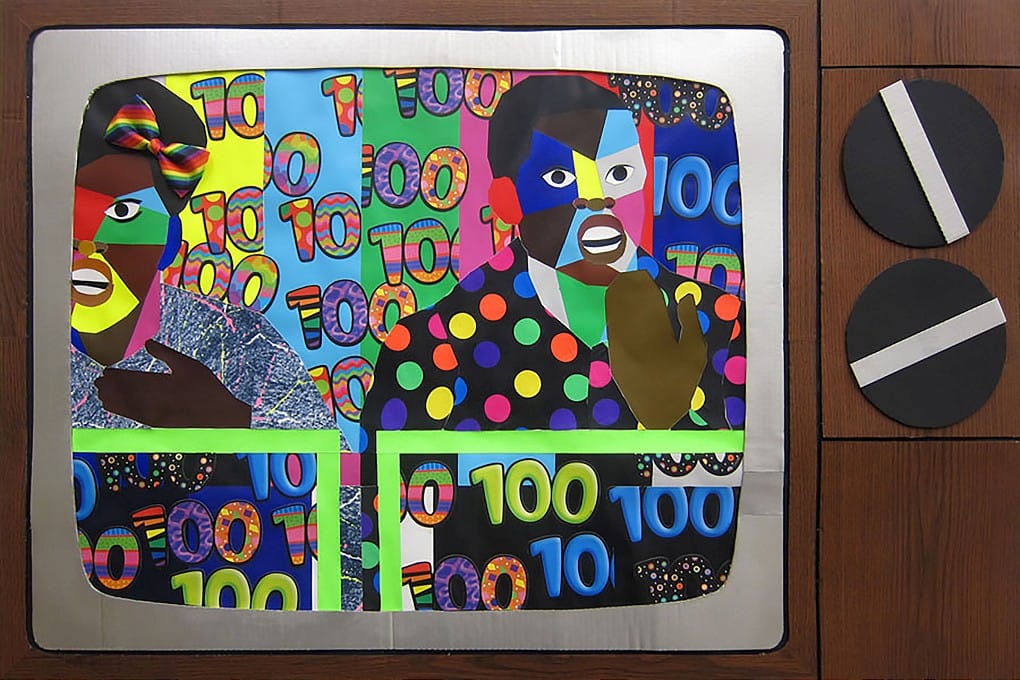

Part of the exhibition curator's goal was to challenge preconceived notions of what race is, as well as the idea that it’s definable, that it even exists.

In 1969, singer and activist Nina Simone galvanized the Civil Rights movement with her proud anthem “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” written in memory of Lorraine Hansbury, the first black woman to write a play performed on Broadway. “When you’re young, gifted, and black / Your soul’s intact,” Simone sang. “To be young, gifted, and black / Is where it’s at.” Fifty years later, in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement, these affirmations are just as sorely needed as when Simone first sang them. Now, artist Hank Willis Thomas has curated a group exhibition inspired by and with the same name as the song — one of his “all-time favorites” — which is currently on view at the Goodman Gallery in South Africa.

“There are so many different artists dealing with blackness in their work today,” Thomas told Hyperallergic. “They’re all looking at blackness as a muse, and defining this muse in really divergent ways. This show was a perfect opportunity to pull them all together.”

What unites the artists’ work is how it all reflects the show’s overarching thesis: “Black lives matter, and all lives are black lives,” Thomas says. The artists in the show are from nine different countries and all identify with blackness, though “they might not all be seen as black by most people,” Thomas says. Part of his goal was to challenge preconceived notions of what race is, as well as the idea that it’s definable, that it even exists. “I personally don’t believe in race. I don’t really believe in blackness,” he says. “That’s the problem I’m contending with in this exhibit, this idea that blackness is a thing you can’t put your finger on.”

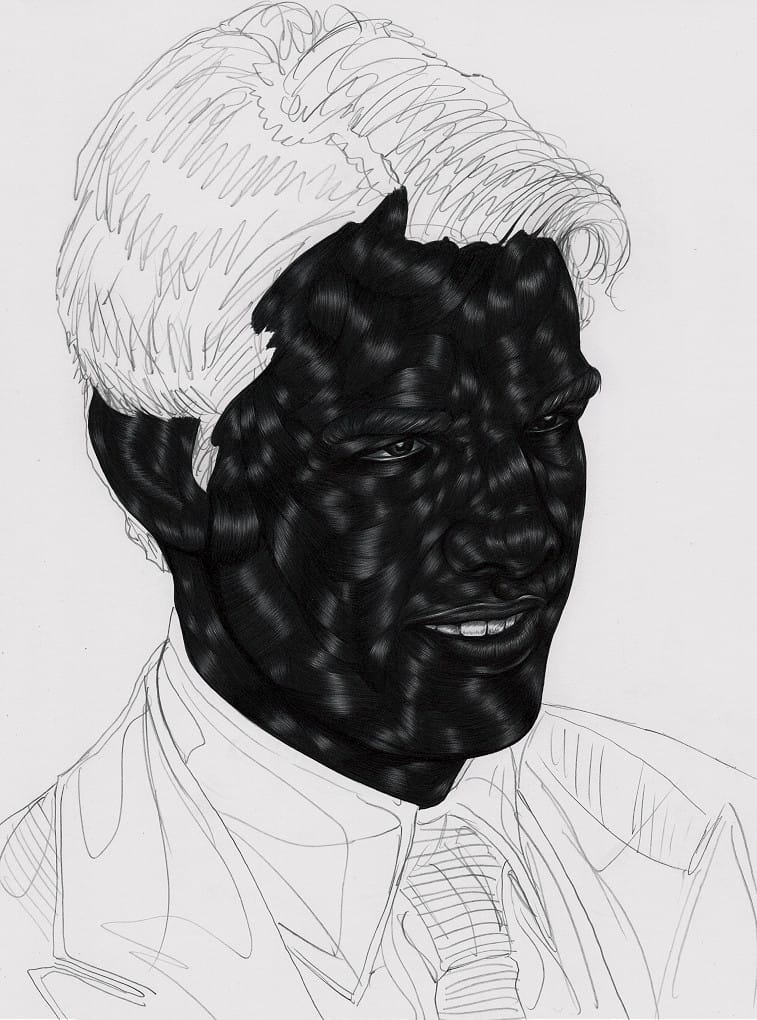

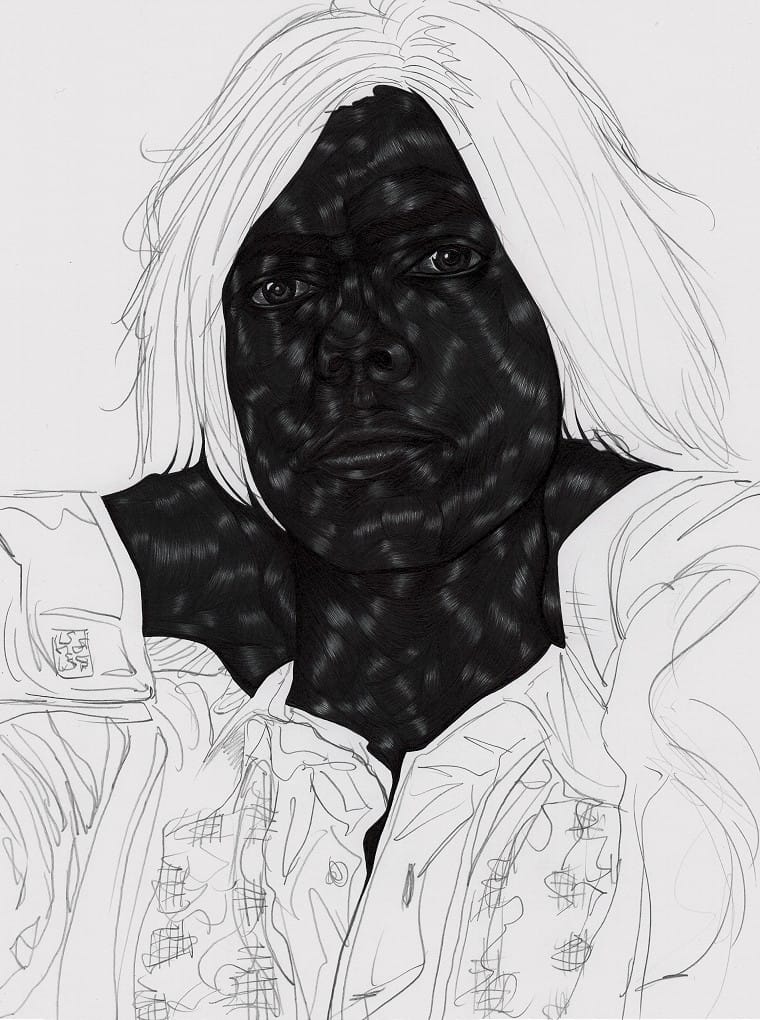

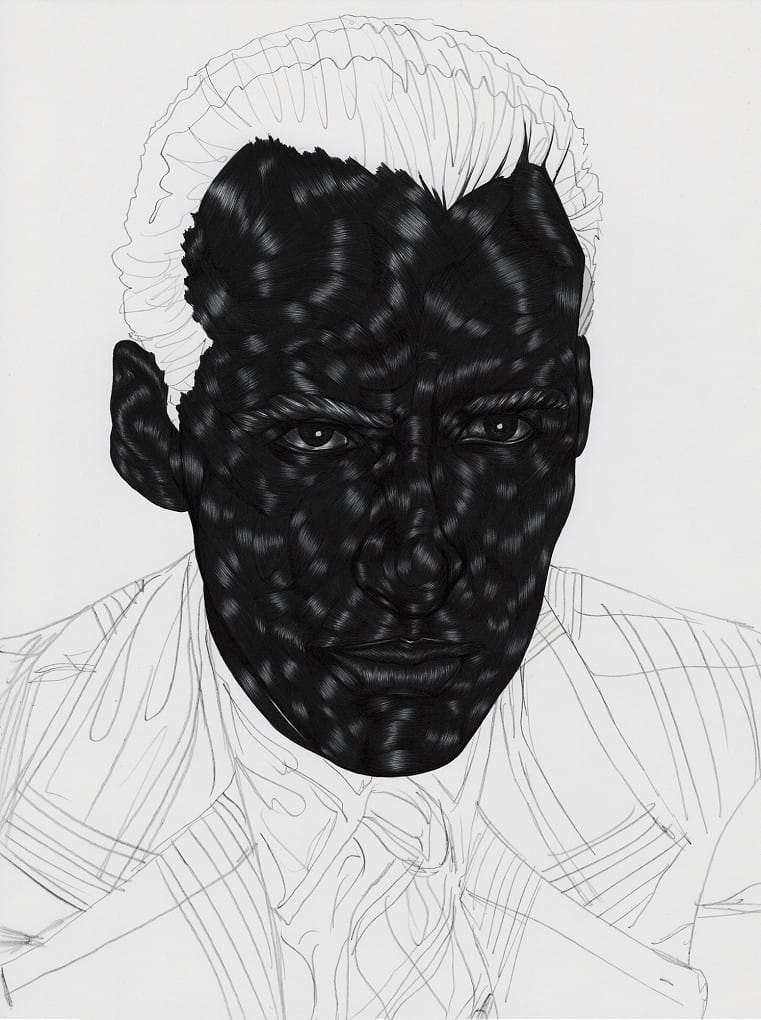

Artist Toyin Ojin Odutola reflects this notion in her portraits of famous white male figures, like President Herbert Hoover, with their faces darkened in black ballpoint pen. With their features obscured, these iconic men become virtually unrecognizable. “Odutola is exploring the kind of erasure that often happens when things are labeled or defined as black,” Thomas says. “How, if you define someone as black, they’re often inherently seen as somehow less valuable. She’s trying to expose and complicate that, how these famous white men become much harder to recognize for their individuality when they’re rendered in this blackness.”

Titus Kaphar’s “George Washington’s Chef” is a conceptually and visually similar response to this theme of brutality and erasure: a portrait of a chef with a featureless face covered in smeared tar.

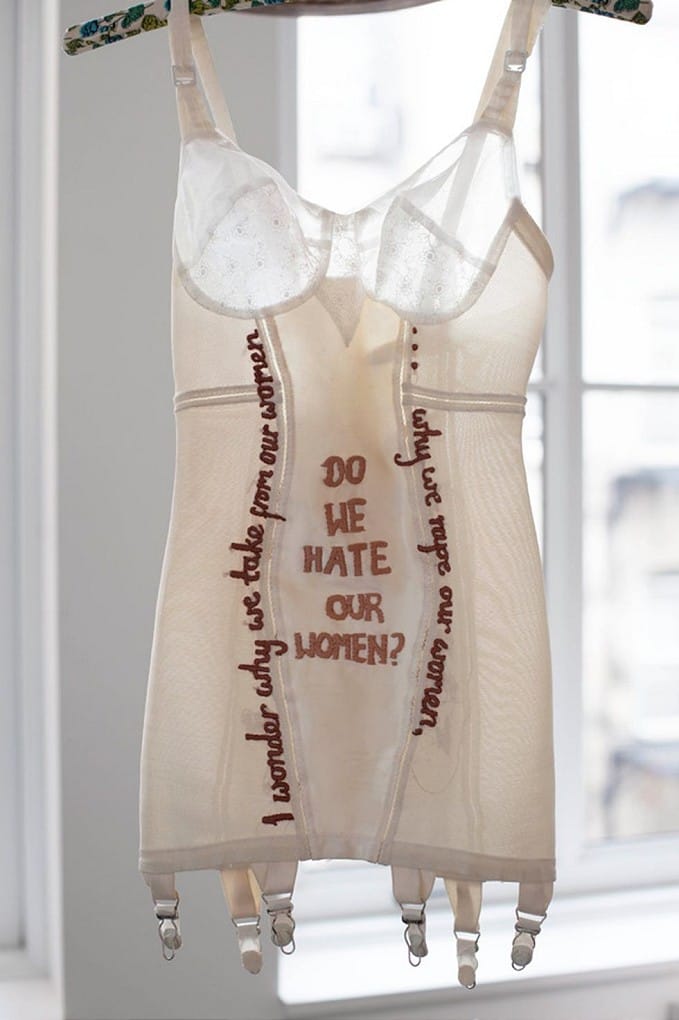

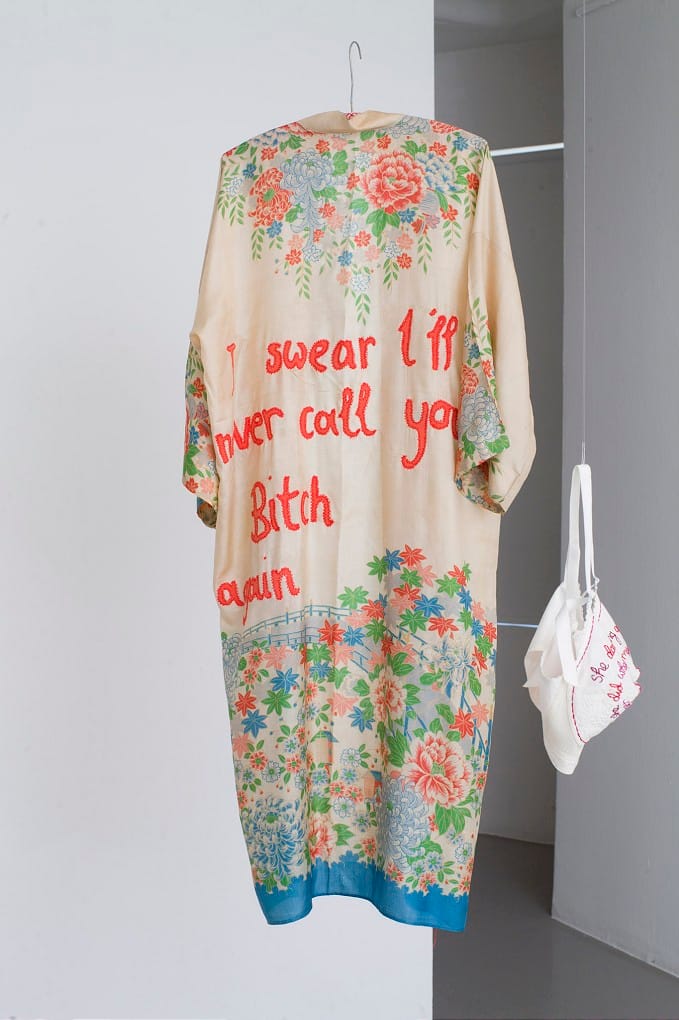

British artist Zoe Buckman explores intersectional themes of feminism and blackness in her project Every Curve. She’s embroidered lyrics from rappers Tupac and Biggie in pastel thread onto vintage slips, bras, and other lingerie — with phrases like “Bitches, I like them brainless,” stitched in orange on a ’50s cone bra, and “I like ‘em cute, round tits and fat asses” on a lacy mint-green slip.

The discordant juxtaposition of delicate, traditionally feminine clothing with these harsh lyrics highlights their misogyny, evoking how these words would look stitched onto women’s bodies. “Zoe Buckman loves hip hop culture but also has this ambivalence about the way the same people who say these incredible messages are sometimes found saying things that are really problematic about women,” Thomas says. Buckman adds nuance by including more self-aware, less misogynistic lyrics — like Tupac’s “I’ll never call you bitch again” and “Why do we hate our women?” — avoiding demonization of the hip-hop artists she’s commenting on here.

Thomas hopes the show will open up discourse within artistic communities in the US and South Africa, broadening the scope of understanding of blackness and racism as a global problem. “South Africa is a country with a very complicated history that’s not so different from the US in a lot of ways,” he says. “But rarely are things discussed in an international, transnational way. That’s where the idea for the show came from: thinking about blackness in a local context, and also thinking about it in an international context.”

To Be Young, Gifted, and Black continues at Goodman Gallery until November 11th.