Beer With a Painter: Michael Berryhill

“You can’t think your way through a painting,” the artist said during our conversation at his home studio in the Catskills. “You can only act, mark, or feel your way through.”

ELLENVILLE, New York — The word “GUILLOTINE” was drawn in charcoal capital letters on the wall of artist Michael Berryhill’s basement studio when I visited him in November, shortly after Zohran Mamdani was elected mayor of New York City. Berryhill was fired up about the state of the country but optimistic. His home is a museum piece of the 1950s, with plywood floors, ranch-style corner windows, and pink-tiled and wallpapered bathrooms. But the way he and his wife, musician Eleanor Friedberger, use it feels like a form of resistance against that period of conformity: In addition to the basement studio, there is a music studio and small performance space. The upstairs living room, where we talk over a late-afternoon beer, is filled with color, mid-century furniture upholstered in pink and yellow, and patterned accents.

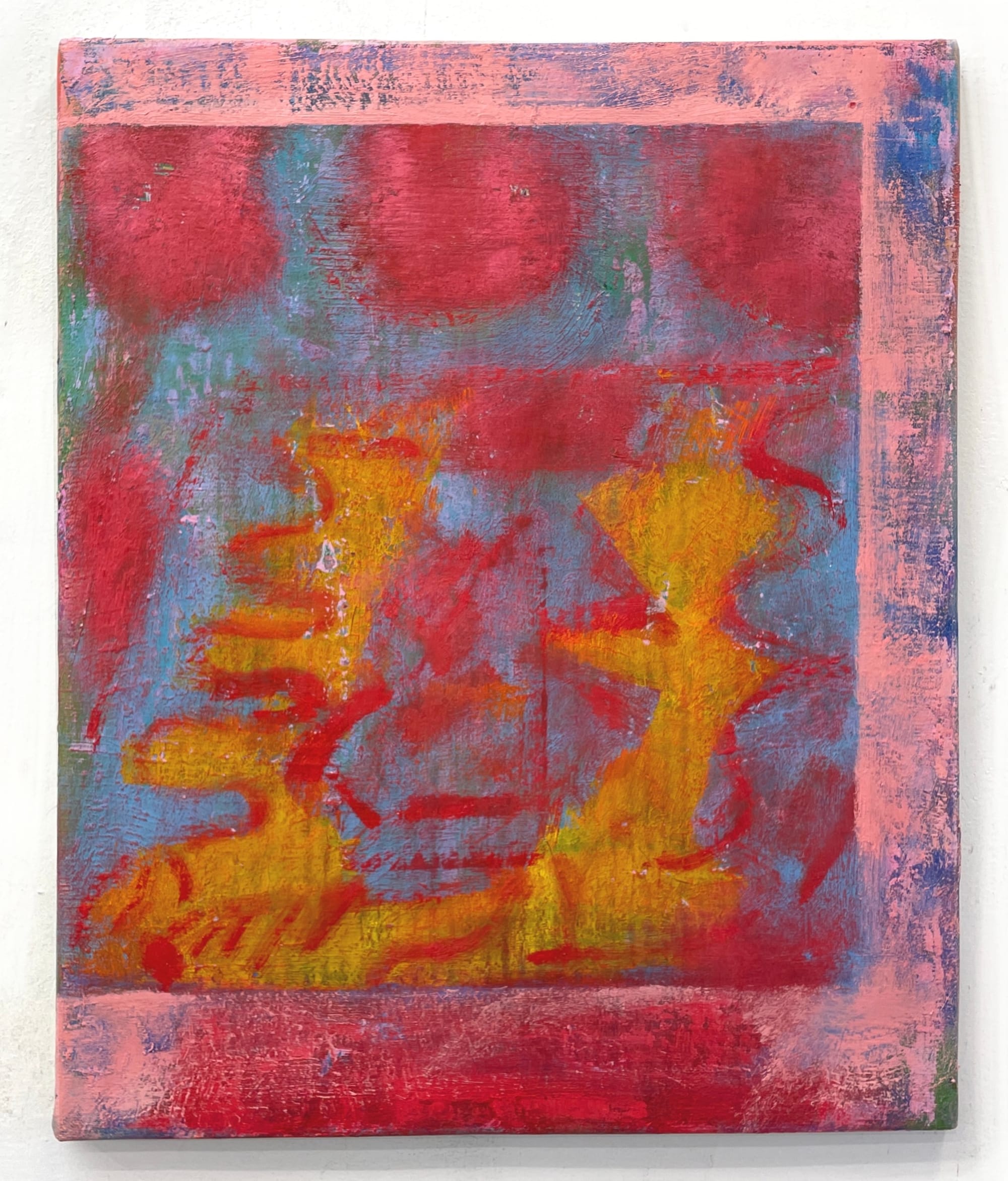

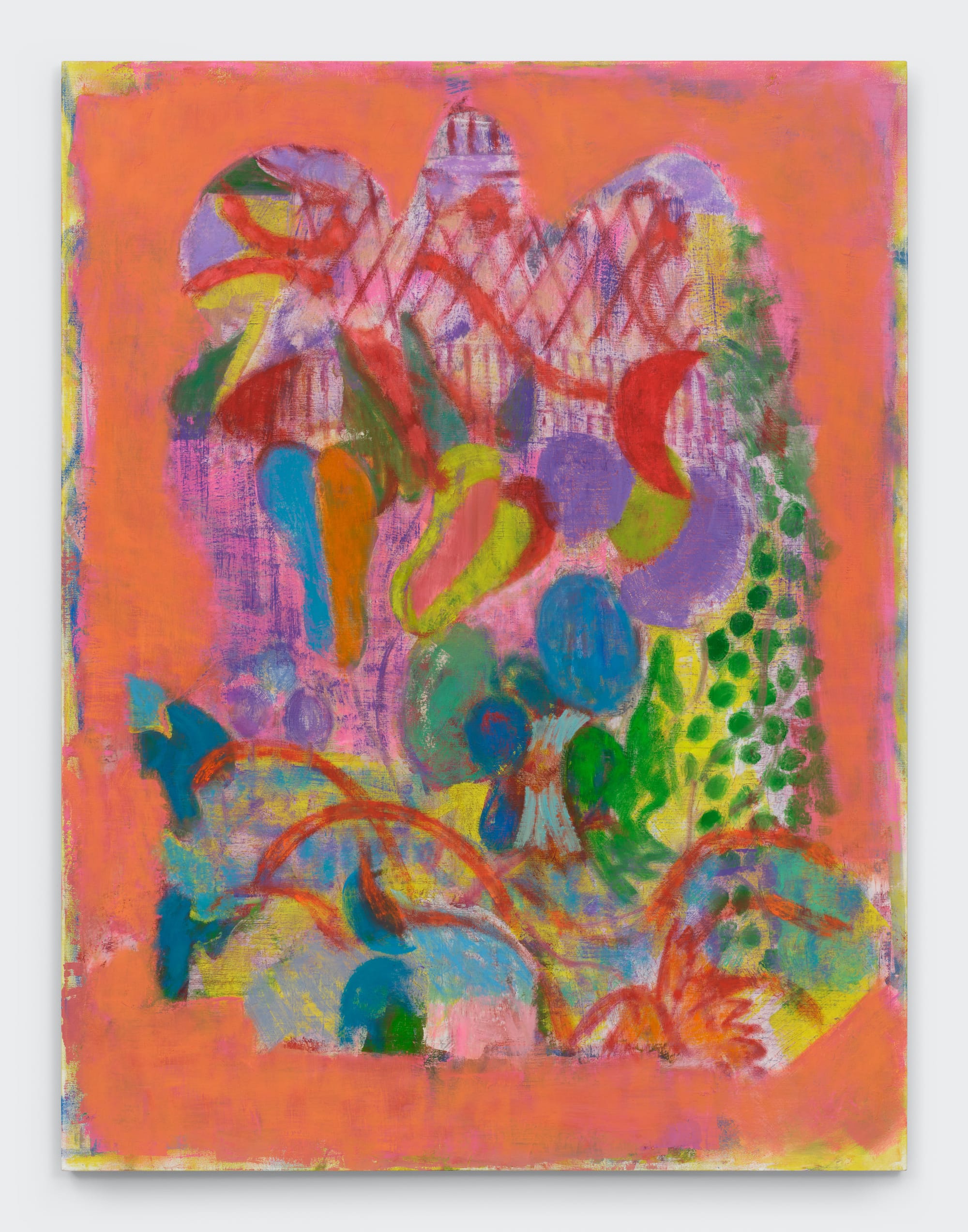

Berryhill’s painting, too, enacts its own form of resistance. Although his is a vibrant palette of pinks, oranges, blues, and yellows, it’s also trippy and electric, especially under the fluorescent tube lighting he prefers. It’s too passionate for a Garden of Eden and more aligned with the unsettling nature of Philip Guston’s pinks. And while his paintings are generous and luscious, he always favors a dry brush — drawing into the weave of the linen canvas and using it as resistance, scraping away as much as he adds. He both forms and resists image-making, with some paintings clearly depicting lions, birds, figures, tabletops, and the sun and others shying away from figuration.

Michael Berryhill was born in El Paso, Texas, in 1972. Berryhill received his BFA at the University of Texas (UT), Austin in 1994 and attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture before graduating with his MFA from Columbia University in 2009. He has been the subject of solo exhibitions at Derek Eller Gallery, Kate Werble Gallery, and KANSAS Gallery in New York City; Night Gallery in Los Angeles; La Maison de Rendezvous in Brussels, Belgium; and Galería Marta Cervera in Madrid, Spain.

Hyperallergic: Can you tell me about your early exposure to art? Did you look at art or draw as a child?

Michael Berryhill: I grew up in El Paso, Texas. Luis Jiménez, the Chicano sculptor, was from my town. I would see his big sculptures downtown, but I didn’t realize there was an art world out there. As a young person, I was obsessed with the “normies” like Norman Rockwell and Frederick Remington.

When I was five years old, Star Wars got me drawing. It was a fantasy world that echoed the real world. The spaceships were dirty and dented. Those details made me want to recreate it. I made comic books and a zine with a friend at school. I was the kid who could draw, and I recognized it as something that got me through the world. It was an endless activity.

H: How did you end up getting your BFA at UT Austin, and who did you study with there?

MB: My parents, who were high school teachers, said, “Don’t get a BFA; that’s crazy.” They knew I was taking a lot of art classes, and they told me to get a design degree. I lied to them. I did take a design class, but I found it so boring that I didn't take any others. I was taking painting classes and print classes. The school was so affordable that no one could complain in the end.

Austin was really fun; you could see live music every night if you wanted. There was a group of amazing artists studying at the same time, like Erik Parker, Daniel Dove, and Violet Hopkins. Peter Saul had a huge influence on us. He hated academia and authority, but he was a great example of permission-giving. The highest compliment was to call something funny or weird or just unexpected. UT had a strong, competitive studio culture, which was contagious. I caught the bug.

Leo Steinberg gave a talk when I was at UT that had a huge impact [on me]. He spoke about how radical some Madonna and Child paintings are, and Michelangelo’s “Pietà” sculpture. For example, Mary’s shoulders are absurdly huge to accommodate the male body on her lap. He was addressing different levels of analysis: first, to be interested in an artwork, then, to take it apart, and finally, to let it haunt you. I began to understand that well-known works of art were strange. I wondered if you could be strange from the onset, and bring the normal in later.

H: You went to Columbia to get your MFA. What was that period like?

MB: I moved to New York and had a job in advertising for 10 years. I knew I had to get organized, financially and otherwise, before going to grad school. I became obsessed with seeing every gallery show. Once you do that for a number of years, you stop making art or you go all in.

Everyone in advertising was trying to do something else, so I was surrounded by other artists, musicians, and actors. The highest paid “creatives” in advertising are fully phoning it in. The rest of us make fun of them and do our thing and hopefully quit someday. Graduate school got me to stop working at a job.

I was lucky enough to have Charline von Heyl as one of my mentors at Columbia. She was amazing to talk to. She said the highest level of artmaking is when you wonder afterwards, “How did I make that thing?” Once you experience it a few times, you want to get to that place over and over again. That experience is transferrable to the viewer. If you, as the artist, are genuinely interested, someone else is going to be interested.

H: I know that the imagery in your work is unplanned, and it straddles the line between abstraction and recognizable forms. How does it develop?

MB: Most of the work starts with a doodle, with a foreground and background. Then it is transferred from sketch to painting. Sometimes a mark or two can suggest a face, an architecture, or a very specific landscape. I'll head that way for a while and describe more. Then I may be suspicious, and back out. But I never start a certain form. It is always found. I trust that, because it’s like going down a clue-finding mission.

H: Is there a moment when you feel the image becomes a carrier of meaning, such as the group of paintings with a parrot?

MB: Initially there was a thoughtlessness to it, but a parrot can be super colorful, which is fun. People will accept any colors on it. A parrot is a mimic, and could be a metaphor for the artist trying to make good paintings and mimicking great paintings.

H: I know you are also interested in the tension between the nameability of objects and the abstraction of the painting. Can you talk about how it manifests in your work, and how people might not even recognize the image at first?

MB: It is like having your cake and eating it too. People might walk away wondering if they saw a parrot or a lion, or just remember a pink thing, or a color feeling. It can function just as a painting, rather than a narrative.

In art history, meaning shifts over time, even if it was created for a specific intent or commissioned. My favorite example is deeply Christian imagery. I went to Arezzo, Italy, last summer and looked at Piero della Francesca paintings, many of which are still in churches. Even though I was raised Catholic, and completely steeped in it growing up, I didn’t think about religion at all. It is proof that, at some point, the power of the painting has nothing to do with the literal intent.

In Piero’s work, there are peculiar forms, like a shape between two figures. These forms were probably accidental, but he made decisions to leave them. He knew there was something interesting that had nothing to do with the story. Everything was prescribed by the patron and the church, but you can feel him as an artist searching for something else. He willed the discovery of strange and powerful forms. And that is the thing that endures, no matter where you come from. Any human being can feel it.

H: Can you tell me about your high-keyed color palette, which suggests a kind of tropical Garden of Eden?

MB: I want the paintings to be really appealing. I think about the Pre-Raphaelites, how they were looking at Old Master paintings with brown palettes. New pigments and colors became available, and they wanted to use them and make work that was fantastical and dreamy. They were glowing, with jewel-like moments.

It is about seduction. It’s about something that looks different in different light situations, from sunlight to very dark spaces. I loved the exhibition of Chris Ofili at the New Museum in 2014 where there was one darkened gallery. The images would flicker. Paintings can haunt you, even if you don’t think you are taking them in deeply. The color is about overwhelming the senses.

H: I can see that you are working on several paintings at once. Do you always do this, and how does it affect the work?

MB: In the studio, if there’s a painting hanging to the left or right of another one, I pretend they are in the same world, and think about what might exist off to the side. One painting is always working better than others. I move the dull ones next to the interesting ones and try to get them to infect each other.

As I go from one painting to the next, I want them to look different even though it’s still the same hand. I think about a fantasy retrospective filled with surprises, where the first painting and the last look completely different.

I usually spend about nine months on a group of paintings. Not valuing labor, or my own time, is the most important thing. You can’t feel bad about subtracting. It is part of making a good painting. I also learned to devalue good drawing — the copyist in me, the good student. You can’t privilege legibility, accuracy, or depth.

I'm interested in things that are intellectual, but they won't get you out of trouble in the studio. Intellectualizing anything about making art doesn't make sense to me. Cave drawing is closer to what I'm interested in. It's direct, sensorial, and experiential. You can’t think your way through a painting. You can only act, mark, or feel your way through.

H: You’ve written the word “GUILLOTINE” on your studio wall. Why?

MB: I wrote that word on my wall because I am trying to get some of that energy going. I've been having conversations with artists I mentor about how to make art for this period. I tell people to make art for the world they want to live in.

I believe in making work for the society you dream of. The work looks surprising because you are free, and this society would understand it, appreciate it, and be moved by it. You make work for the audience that you respect. I don’t respect fascists and conservatives, or billionaires who want to live around suffering people. My art is not for them. I make art for artists, and for sensitive people. I’ll battle it out politically on the street, but in the meantime, I’m going to make nice paintings for the time right after this.