Chicago’s Plan for Sick Trees: Turn Them into Art

Artists turn trees devastated by a pest into works of public art, calling attention to the problem and creating opportunities for unexpected artistic encounters across the city.

CHICAGO — As its name suggests, the emerald ash borer is a beautiful little green bug, with an armor that shimmers like its namesake precious stone. Its appearance makes it one of the more attractive insects in North America, but it’s also one of the most destructive pests to have invaded the United States (where it arrived from its native Asia). Since 2002, when the metallic beetles were found feeding on ash trees near Detroit, they have spread over many miles and killed hundreds of millions of ash trees in 31 US states as well as in Ontario and Quebec.

Typically, many of these trees are cut down and removed. In Chicago, however, a city-funded model has emerged to transform them into signposts to educate the public on this critical environmental issue. Since 2014, artists have sculpted dead or dying trees, creating large, unexpected works of public art in neighborhoods around the city.

Known as the Chicago Tree Project, the program is run by Chicago Sculpture International, which partners with the City of Chicago and the Chicago Park District to select about 10 artists every summer from a pool of applicants. Anyone around the country can apply, and artists receive a modest stipend for their work. By transforming trees in residents’ everyday settings, organizers hope to spur curiosity about the project and create dialogue around both a local problem and the broader issue of climate change.

“Because of global warming, this pest has found a more favorable environment than it has had in the past,” Christine Perri, Outdoor Exhibitions Chair of Chicago Sculpture International, told Hyperallergic. “We see this project as extending the life of these trees that normally would have been removed when they were determined to be no longer viable.”

By now, with the temperature dropping, most of this year’s artists have already finished their trees or will soon complete them. On a recent Thursday, I watched artist Janet Austin and her assistant work on a tall ash tree on the edge of Palmer Square Park. They had debarked the tree in September and were carving a maze that wraps around its naked truck — a design that nods to the winding tracks, known as galleries, that emerald ash borer larvae make when they feed beneath bark. Austin also created about a dozen bronze sculptures of the larvae that she was going to embed into the tracks, so the final piece literally depicts the tree under attack.

“Artists are addressing it in all different ways, but I like this topic because it happens to relate to my work,” she told Hyperallergic. “I often make art about pests or unwanted things that we’re trying to fight.” She pointed out another dying ash tree across the street, its tall branches nearly all naked. “One problem is that a lot of ash trees were planted many years ago, along all these boulevards and in all of the parks,” she said. “If the lesson is anything, it’s that we’ll be more careful with biodiversity so [the beetles] just can’t hop from one to the next and kill so rampantly.”

Ash trees make up about 17% of Chicago’s street tree population, and city crews are working to slow the infestation while treating affected trees. In the meantime, the Chicago Tree Project will continue searching for artists to assign trees that are structurally stable. Artists who are interested should look out for Chicago Sculpture International’s national call for proposals in February. Submissions are then sent to the Chicago Park District, whose team makes the final selections.

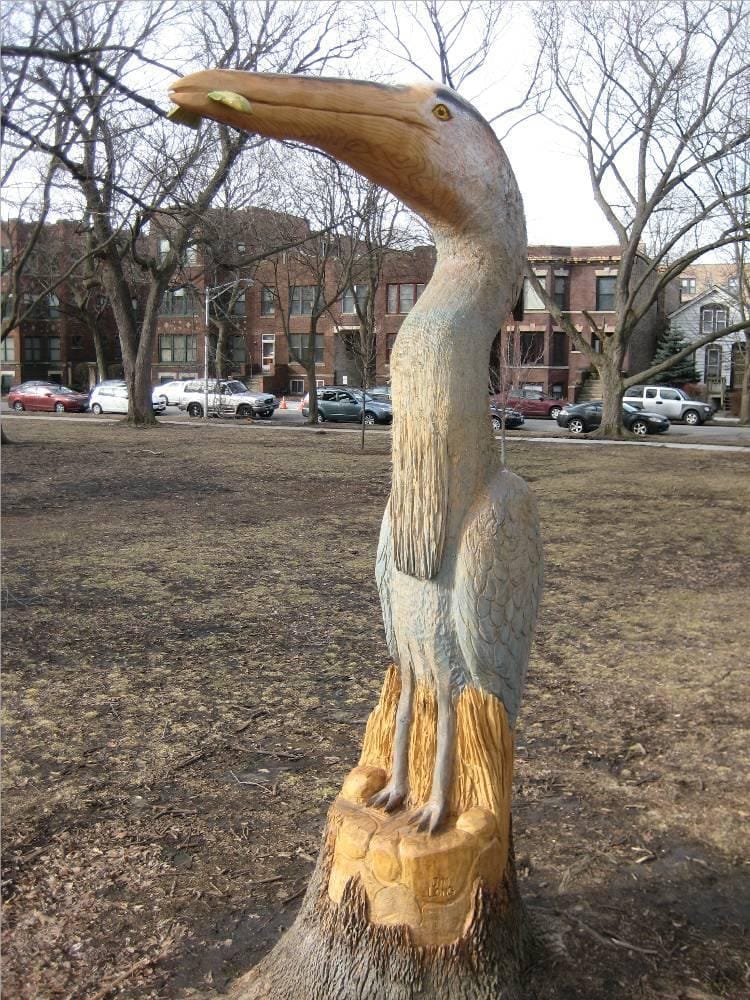

The program essentially presents the city with a growing outdoor exhibition, as each finished tree remains in place for as long as it is secure. In Lincoln Park, five trees depicting peaceful figures with clasped hands still stand tall, carved by local artist Kara James in 2014; in Nichols Park, a tall heron by artist Jim Long has gazed upon its surroundings for two years. The Chicago Tree Project gives artists an opportunity to work on a large scale, and for some, a chance to experiment in a new medium. At the same time, it introduces whimsical encounters into public spaces — and creates a citywide treasure hunt of sorts.