England Gives “Pride of Place” to Historic LGBTQ Sites

Historic England's Pride of Place project aims to recognize overlooked sites of LGBTQ history and protect them as part of the country's heritage.

Historic England’s Pride of Place project aims to recognize overlooked sites of LGBTQ history and protect them as part of the country’s heritage. The initiative was launched last June, and thanks to research led by historians at Leeds Beckett University, six sites were newly recognized on September 23.

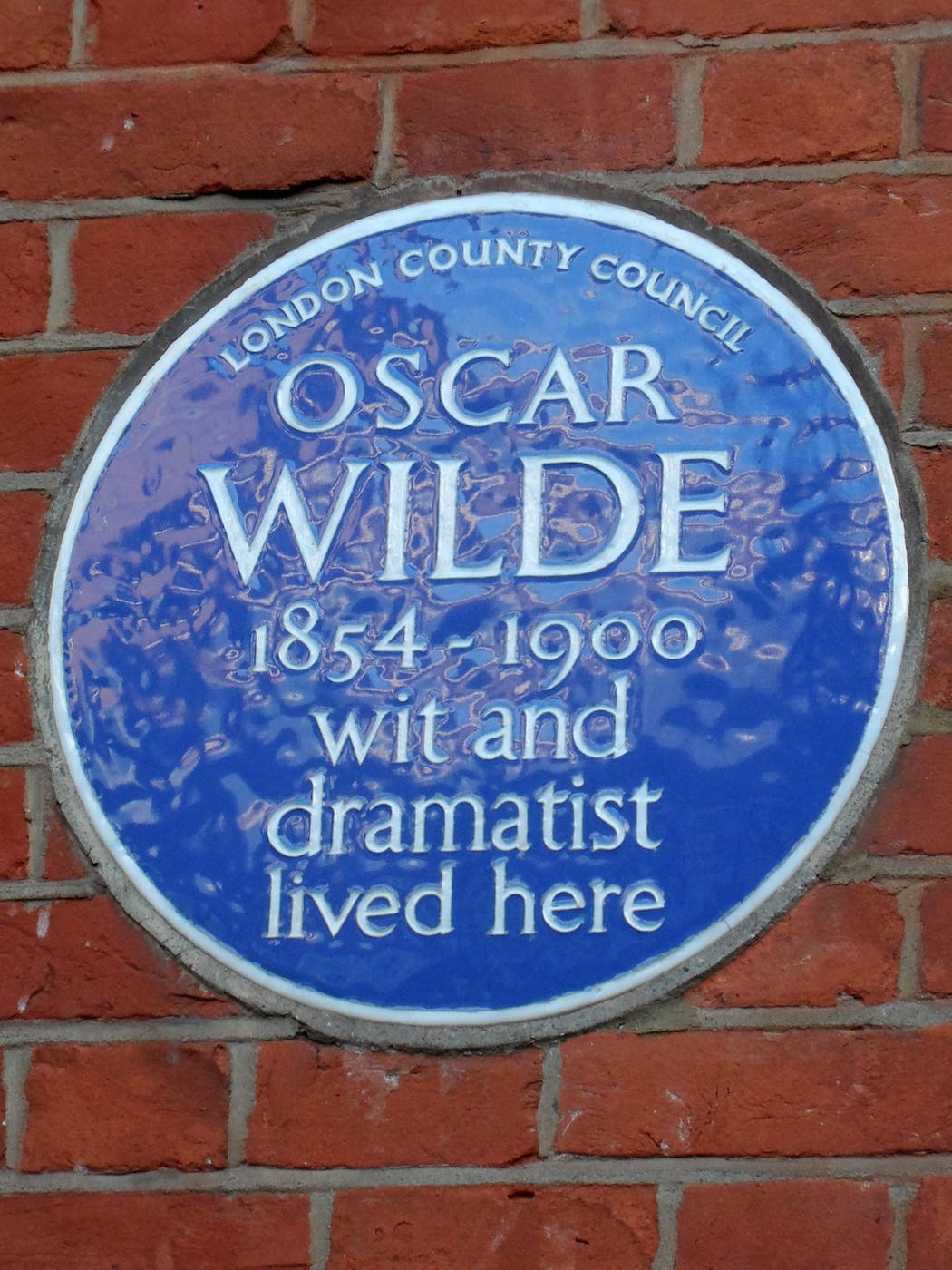

Those designations include a new Grade II listing for the grave of 19th-century Egyptologist and women’s rights advocate Amelia Edwards at St Mary’s Churchyard. Edwards is buried alongside her long-term partner Ellen Braysher, their tomb appropriately marked with an Egyptian ankh. Meanwhile, LGBTQ context was added with relistings for author Oscar Wilde’s home at 34 Tite Street in London, where he lived up until his 1895 trial for “gross indecency”; 19th-century adventurer and writer Anne Lister’s Shibden Hall home in West Yorkshire; and the Red House in Aldeburgh, Suffolk, where 20th-century composer Benjamin Britten resided with partner, tenor Peter Pears. The Angela Burdett-Coutts Memorial in the St Pancras Old Church burial ground in London was also upgraded to Grade II listing. The memorial fountain and sundial commemorate the people disinterred there during 1860s railway construction; among them is 18th-century transgender spy Chevalier d’Éon. Angela Burdett-Coutts herself was a baroness and philanthropist who lived for over 50 years with her partner, Hannah Brown.

Duncan Wilson, chief executive of Historic England, stated in a press release:

Historic Buildings and Places are witnesses to events that have shaped our society. They hold real and tangible evidence of the way our nation has evolved. Too often, the influence of men and women who helped build our nation has been ignored, underestimated or is simply unknown, because they belonged to minority groups. Our Pride of Place project is one step on the road to better understanding just what a diverse nation we are, and have been for many centuries. At a time when historic LGBTQ venues are under particular threat, this is an important step. The impact of the historic environment on England’s culture must not be underestimated, and we must recognise all important influences.

The Pride of Place listings not only reinforce these sites’ queer history, they also provide better preservation protection. For instance, last September’s Grade II listing supported by Historic England for the gay pub Royal Vauxhall Tavern assures that demolition or alterations can’t happen without special permission. Such sites also often speak to the experience of gay life in England before the Sexual Offences Act partly decriminalized homosexuality in 1967. One of the listings updated this month is for the 1930s home of Gerald Schlesinger and Christopher Tunnard, featuring a bedroom with a moveable wall to separate it into two spaces, if needed.

Along with the listings, Historic England released a freely downloadable guide for communities that details how to protect LGBTQ-related buildings in the face of redevelopment. The organization’s current research is also available in a new online exhibition, and anyone can nominate places through an interactive digital map, which, since its launch last year, now has over 1,600 pins.

The ultimate goal of Pride of Place is to better recognize the diverse people who contributed to England’s story — something that’s sorely needed in countries around the world. For instance, this June, President Obama declared the Stonewall Inn in New York City a national monument, the first of the United States’ over 120 national monuments to recognize LGBTQ heritage. Each listing like that is a small step that adds to the dialogue of history.