Florida’s Indigenous Artists Take Center Stage at Miami Art Week

An exhibition organized by the HistoryMiami Museum and the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum is an ode to Seminole creativity and resilience.

Each December, thousands of art world denizens descend on Miami for a weeklong extravaganza anchored by fairs like Art Basel Miami Beach, which spotlight works by artists around the world. This year, two museums hope locals and tourists alike will also spend time with the art of some of the region’s original inhabitants.

The exhibition Yakne Seminoli (“Seminole World”) at the HistoryMiami Museum gathers works by over 25 Seminole artists across traditional and contemporary mediums — not just beadwork, patchwork, and basketry, but also painting, photography, and even AI. Organized in collaboration with the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum on the Big Cypress Reservation in the Everglades, the show aims to convey to visitors that “Seminole history is Florida history.”

For as long as the Seminoles have called Florida home, they’ve had to defend their right to be there, persevering through the Long War in the 1800s to the United States government’s chilling “termination” policies of the mid-20th century. This year saw a new chapter in that struggle when state Republicans recklessly erected the notorious Alligator Alcatraz immigrant detention center in the Everglades, just a few feet away from the traditional villages, sacred burial grounds, and ceremonial sites of the Seminole Tribe and the closely related Miccosukee Tribe.

A lawsuit led by environmental advocacy groups with Miccosukee support resulted in a court order to wind down operations at the prison in August, but the facility remains open, holding migrants with little legal recourse; the whereabouts of hundreds of detainees are reportedly unknown. Decades ago, in the 1970s, Indigenous leaders had been part of successful efforts to halt construction of the Dade-Collier Transition and Training Airport, where Alligator Alcatraz now stands.

Survival, adaptation, and relentless creativity in the face of adversity are the guiding principles of Yakne Seminoli, which shines a light on ancestral practices, their present-day evolutions, and the wholly unique visual vocabulary that emerges from individual artists who are both preserving and reinventing their heritage.

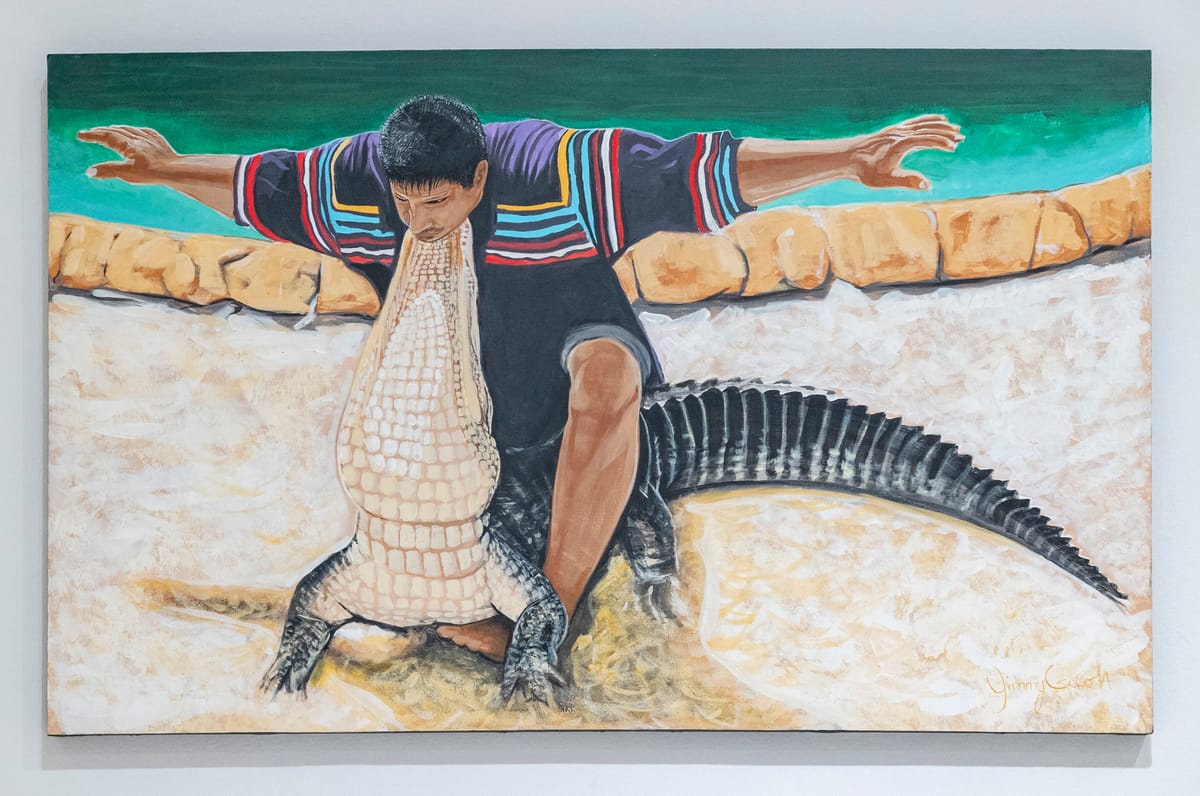

One section dedicated to tourism features an image that even those unfamiliar with Seminole culture might immediately recognize: a painting of a man nonchalantly straddling an alligator, his arms proudly outstretched as he pins the giant reptile's mouth shut with only his chin. The work by the late self-taught artist Jimmy Osceola, known for vibrantly memorializing scenes of Seminole life, is displayed alongside archival photos of airboat rides, safaris, and other attractions that continue to draw intrepid travelers to the Big Cypress Reservation to this day.

Gordon O. Wareham (Panther Clan), director of the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum, contributed one of his own artworks to the show — “Unity” (2025), a digitally altered image of a Stomp Dance led by the revered medicine man Bobby Henry. Wareham told Hyperallergic that he took the photograph and used AI tools to render the figures with an anime sensibility, setting them against a backdrop reminiscent of Seminole camps of the 1940s. The composition’s temporal contiguities convey the message “that we’re still here,” Wareham explained, and “that we still celebrate our ways of life.”

Hali Garcia, a sweetgrass and palmetto fiber artist and educator who was born on the Seminole Hollywood Reservation, also melds past and present in her meticulously woven baskets. The complex technique is typically passed on by older women to young girls. Garcia introduces her own quirky twists, like her love of comics and Nintendo; one piece on view is inscribed with the words of Sonic the Hedgehog’s iconic theme, “Gotta Go Fast.”

“I come from a long line of seamstresses who create our traditional garments and clothing,” Garcia said. “We are a matrilineal society, so I was appreciative that the exhibition also includes items my mother made.”

Patchwork or taweekaache, the Seminole and Miccosukee word for intricate hand-stitched clothing, is included in a section labeled "It's Not a Costume!” that foregrounds the craft's significance in day-to-day Tribal life, not special ceremonies or “public display.”

Many works in the exhibition exude unfettered pride and joy for Native identity: for instance, a life-sized Seminole doll by Ronnie and Mabel Doctor, or Elgin Jumper’s charming painting "Astronaut Girl" (2025), whose titular subject stands on the lunar surface wearing a red helmet with an eagle feather.

A separate section of the show deals with a somber reality. The "Crisis Wall” is dedicated to the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women epidemic, encouraging advocacy and education to address alarming rates of violence. A wall text states that murder is the third leading cause of death for Native women and girls.

Nestled deep in the swampy Everglades, about an hour away from Miami, the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum draws about 35,000 visitors each year, said Wareham. The collaboration with HistoryMiami Museum in Downtown Miami, with its long legacy of co-curating exhibitions with the city’s diverse communities and its own collection of Miccosukee and Seminole artifacts, offered an opportunity to reach a broader audience.

Over half of Miami-Dade County’s residents were born outside the United States, a fact that contributes to the area’s cultural diversity, but also to certain misconceptions, explained HistoryMiami Museum Director Natalia Crujeiras.

“People say Miami is a very young place. Yes, we are young as an incorporated city, but we have tens of thousands of years of history,” Crujeiras told Hyperallergic.

“If all we can do is inspire people to be more curious about the Tribe and their long-lasting influence and how their impact continues to this day, as a testament to their resilience and determination,” Crujeiras added, “then I think we will be successful.”