From the Couches to the Conservation Labs, the Whitney Museum's New Building

They say you don't realize what you were missing until you get it. Well, New York City was missing a building for showing modern and contemporary art.

They say you don’t realize what you were missing until you get it. Well, New York City was missing a building for showing modern and contemporary art. The Whitney Museum‘s new home, designed by Renzo Piano and located in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, underlines just how poorly suited to their purposes the Museum of Modern Art, the New Museum, and the Whitney’s former home on Madison Avenue are.

It’s been nearly 50 years since the latter, the Marcel Breuer building, opened, and walking through the new Whitney you get the sense that, for the past five decades, the museum’s staff has been making a list of problems it wanted to rectify with its next home. More natural light: check. Bigger and more flexible galleries: check. A worthy conservation lab: check. Auditoriums for performances and screenings: check. Dedicated spaces for education programs and studying objects not on view in the galleries: check. A covered loading dock: check. Everything has been done to optimize the display and appreciation of 20th- and 21st-century American art.

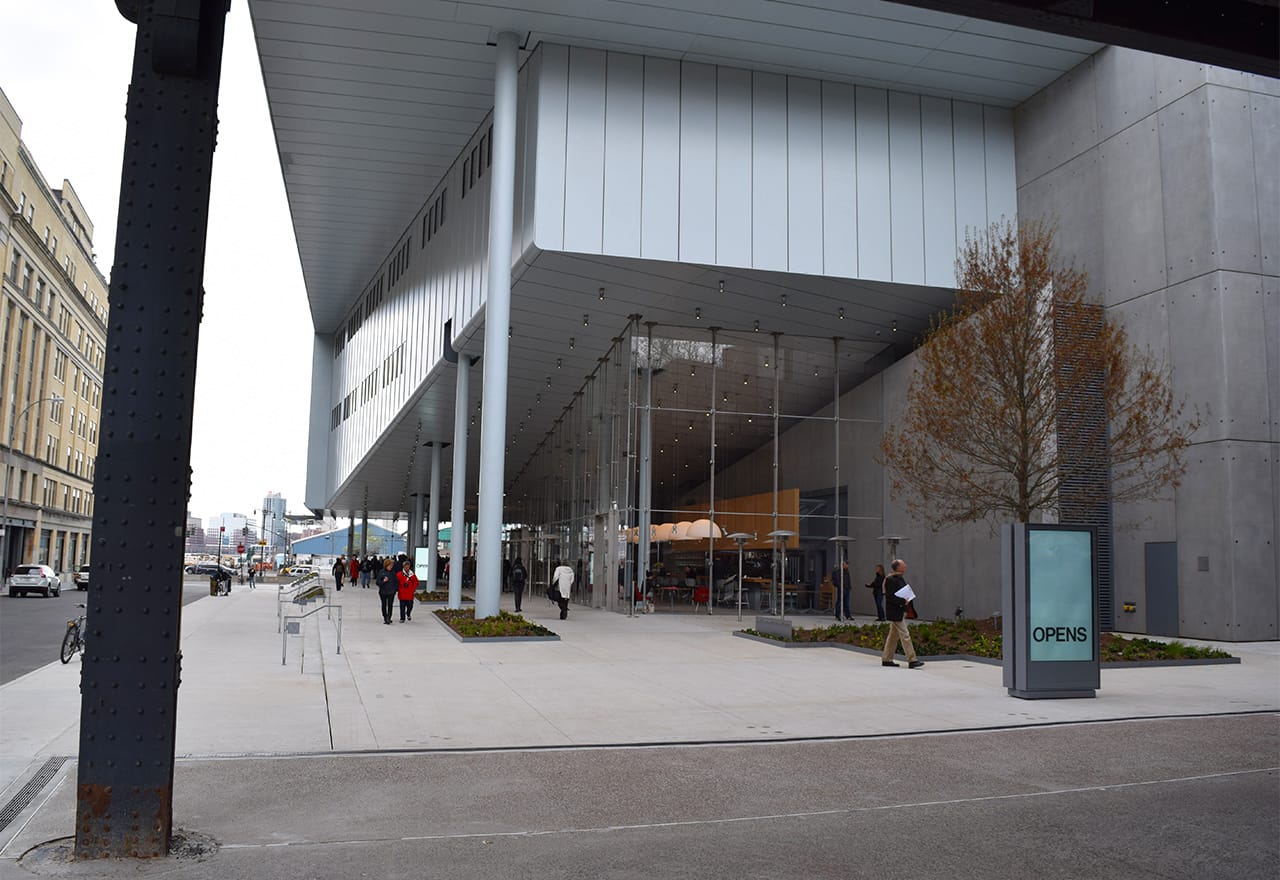

Some feel that Piano’s privileging of interior spaces and back-of-house amenities over outward appearances has resulted in a clunky, inelegant building, but I disagree. With its open, glassy entryway and dramatically bulging, cantilevering upper floors raised on a narrow cement base and a row of massive steel pillars — leave it to an Italian architect to smuggle a stylized Roman colonnade into a contemporary art museum — the new Whitney manages to simultaneously look squat and featherweight, like a plus-size ballet dancer on pointe or a supertanker in a dry dock. The impression that the bulk of the museum is somehow floating makes climbing from its lobby up into the galleries feel like boarding a spaceship.

The new Whitney’s star attractions, appropriately, are the four long galleries on its fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth floors. Each stretches east to west, with walls of windows at either end admitting varying levels of natural light depending on the interior configuration. The resulting vistas face toward Manhattan and the High Line, or across the Hudson toward New Jersey. The eighth floor also benefits from a ceiling made up entirely of skylights. Beyond the glass walls, each level has outdoor exhibition and seating areas thanks to a series of terraces on the building’s east side that are connected by an exterior staircase.

In addition to its abundance of outdoor space, another refreshing feature of the new Whitney building is the openness and accessibility of its staff, conservation, and research areas, which are directly adjacent to the galleries. In the Sondra Gilman Study Center, the public and scholars will be able, by making an appointment, to look closely at any work on paper in the museum’s collection. The adjacent Bucksbaum, Learsy, Scanlan Conservation Center integrates the needs of conservators working on pieces in every medium; today those included a motorized Alexander Calder sculpture, a large Mark Rothko painting, and a fragrant rectangle of beeswax that Robert Gober made to resemble a giant stick of butter. These facilities’ proximity to and visibility from the gallery spaces contribute to a pervasive sense of transparency that one hopes will become the new norm in museum design.

The new Whitney Museum (99 Gansevoort Street, Meatpacking District, Manhattan) opens to the public on May 1.