Henry Moore Foundation Asks Artist Not to Use Sculpture as “Political Statement”

Three years ago, Kansas City–based artist A. Bitterman proposed moving a vacant, dilapidated house, located in one of the city's poorest neighborhoods, to the lawn of the Nelson-Atkins Museum.

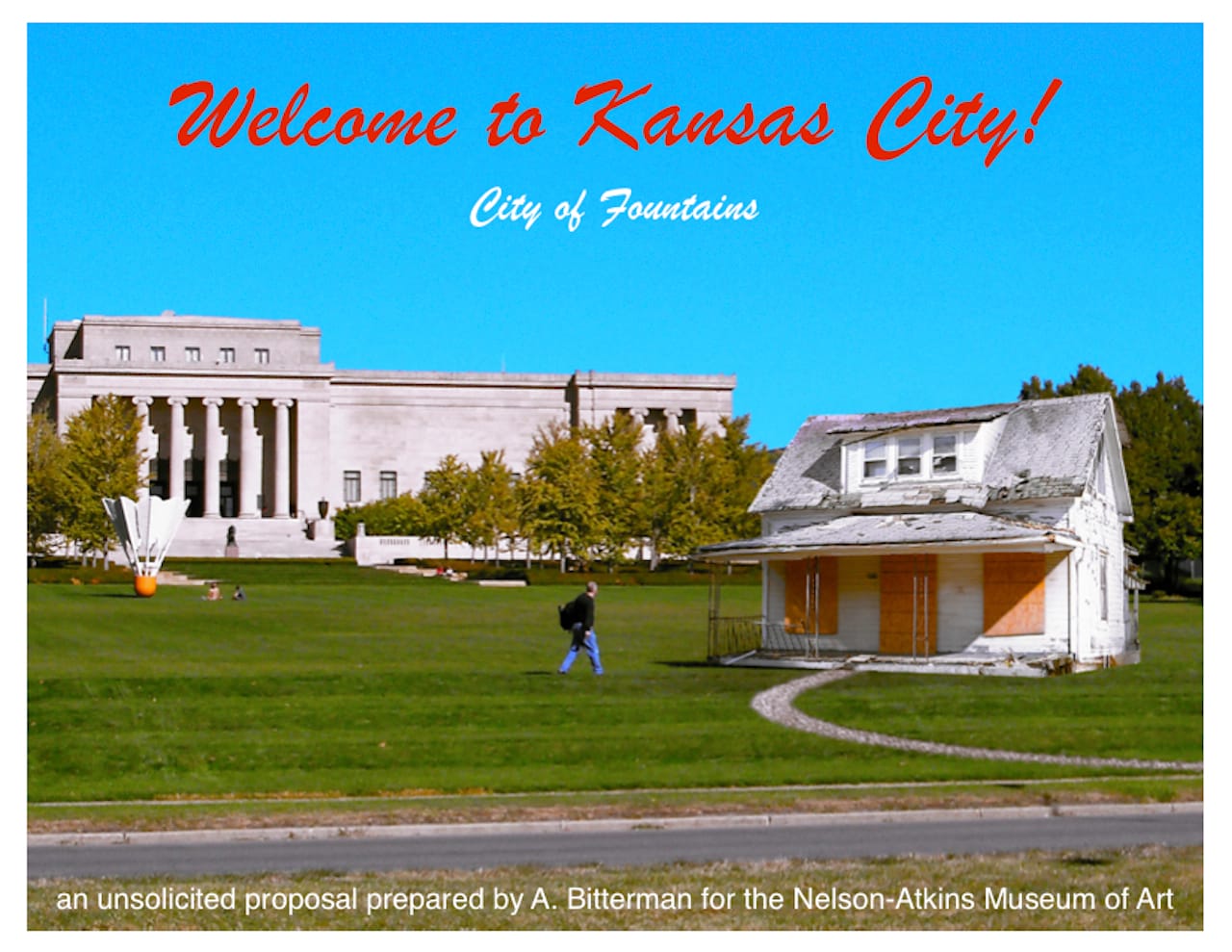

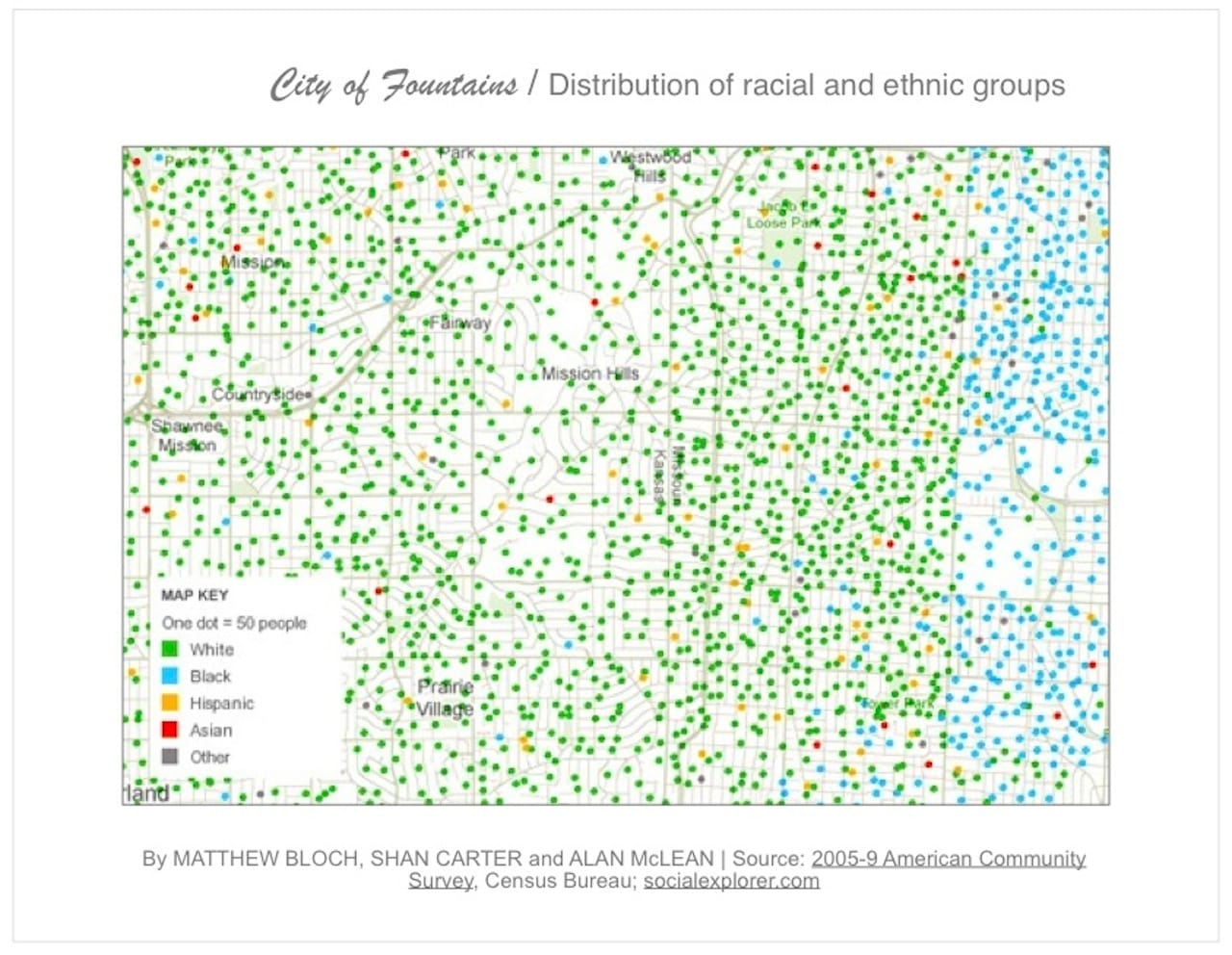

Three years ago, Kansas City–based artist A. Bitterman proposed moving a vacant, dilapidated house, located in one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, to the lawn of the Nelson-Atkins Museum, where it would stand beside the likes of a Claes Oldenburg shuttlecock. In place of the house, Bitterman suggested, the museum should install its prized Henry Moore sculpture “Sheep Piece” (1971–72). The house and the Moore lie on opposite sides of Troost Avenue, a major thoroughfare that has historically divided the city along racial lines. As Bitterman told Hyperallergic, the project, titled “City of Fountains,” “proposes a simple way of disrupting the geographies of exclusion that diminish our humanity.”

The museum has never acknowledged the project. The idea for “City of Fountains” reappeared, according to the artist, “out of the ether” last month on CityLab, and later on Hyperallergic, with a photoshopped image by the artist of the bronze Moore sculpture situated between two residential houses.

Last week, the artist received an email from the Artists Rights Society (ARS) stating that “this photograph appears on several websites including the Hyperallergic website” and “is in violation of [the Moore Foundation’s] copyrights in the work of art.” Adrienne Fields, a spokesperson for ARS, explained the Moore Foundation’s reasoning to Hyperallergic, saying that the sculpture, as used in Bitterman’s project, “crudely cut out and placed in a different location, would not have been the artist’s intentions” and “loses integrity and its sense of weight and scale.” Fields elaborated that the foundation “rarely would’ve granted permission” to use the sculpture to make “a political statement.” In the email to Bitterman, representatives of ARS wrote, “We respectfully ask that you discontinue this use of Henry Moore’s sculpture.”

The artist says he finds the Moore Foundation’s reaction both “unexpected and gratifying.” On the one hand, “their response validates the strength of the work”; on the other, they’ve passed up “a chance to resurrect a body of work doomed to languish in the gardens of privilege and find a new relevance in the context of contemporary art and thought, to be part of a new conversation that seeks equality.”

“If the Henry Moore people were really smart, they’d be backing this project with gusto,” Bitterman added.

Bitterman has since sent another e-mail to Julian Zugazagoitia, the director of the Nelson-Atkins Museum, asking him to “reconsider the project and that we expand it to include the exchange of several Henry Moore sculptures with structures and artifacts from around the city.” He has not received a response. This isn’t the first time that Zugazagoitia has been faced with one of Bitterman’s interventions: in 2010, the artist hung a Wal-Mart sign off of the museum’s Bloch Building. The institution acknowledged the work and considered acquiring photographs documenting the intervention for the collection, but ultimately sent them to the museum’s research library.

Bitterman does not hold high expectations for the realization of “City of Fountains.” “Of course I believe in all of my projects wholeheartedly, but I’m not wishful about them,” he said. “‘City of Fountains’ is a strong and earnest work, and if I were Theaster Gates or Gordon Matta-Clark come back to life, who knows? Maybe then I could afford to be disappointed. As it is, I like working in the margins.”