How We Talk About the Dead

Imagine a person like this: “one of a handful of people who can truly be said to have changed the way we think and write about art, fashion, culture, and celebrity.”

Imagine a person like this: “one of a handful of people who can truly be said to have changed the way we think and write about art, fashion, culture, and celebrity”; someone who “made the avant-garde accessible,” and did things “mere mortals only dream of.” The person being referred to in such exalted terms actually did live and walk among us. She died only a few weeks ago after battling breast cancer. Her name was Ingrid Sischy.

Jesse Doris, writing for Slate, was one of several writers to offer praise of Sischy so lush the reader will assume Sischy had divine powers. Graydon Carter, the current editor of Vanity Fair and a longtime colleague of Sischy celebrates her in similarly adoring language: “She could write about anything;” “she traversed those two hothouses [art and fashion] like a bemused empress;” “she was a fun, conspiratorial gossip, but never with malice or envy;” “her spirit and her work ethic remained heroically steady;” “Not once did I ever hear her complain about the fate she had been dealt.” With an earnestness that does not admit even the suggestion of irony, the epigraph of Carter’s panegyric relates that his piece intends to recall, “Sischy’s genius for mixing the pleasure of friendship with the business of truth-telling.” This is not just sweet; it’s a Type 2 diabetes precursor.

This kind of writing is typical of the genre of eulogy. There is a ritualized habit of using encomiums to recall the dead in reverential terms. According to Martha Gill, Chilon of Sparta is largely responsible for causing this practice to become embedded in the West. Chilon lived during the sixth century BCE and became known after his death as one of the seven sages of Greece. He earned this honorific by propagating such concise and incisive bits of wisdom phrased as regulatory imperatives, such as “know thyself,” and “nothing in excess.” Through him we inherit the injunction: “of the dead, nothing but good [speak]” Gill argues that this is a worthwhile guideline to follow because speaking ill of the dead is more than distasteful, it’s also cowardly. The dead cannot defend themselves.

However, this habit of generosity makes it difficult to separate hagiography from biography. Indeed, the term “hagiography” comes from the tradition of writing accounts of the lives of saints—saintly acts, the trials and deaths of martyrs, miracles connected with their relics and icons. From the Greek hágios, for “holy,” and graphía, for “writing,” we get stories that were written since the second century CE, supposedly to instruct and edify readers while venerating saints. Nonetheless, the scholarship convened around saints’ lives is essentially focused on preservation rather than tutelage. It is less useful in our current moment to mistake expressionistic portraits made by those who adored Sischy for forthright reports of the actual events of her life and their meanings.

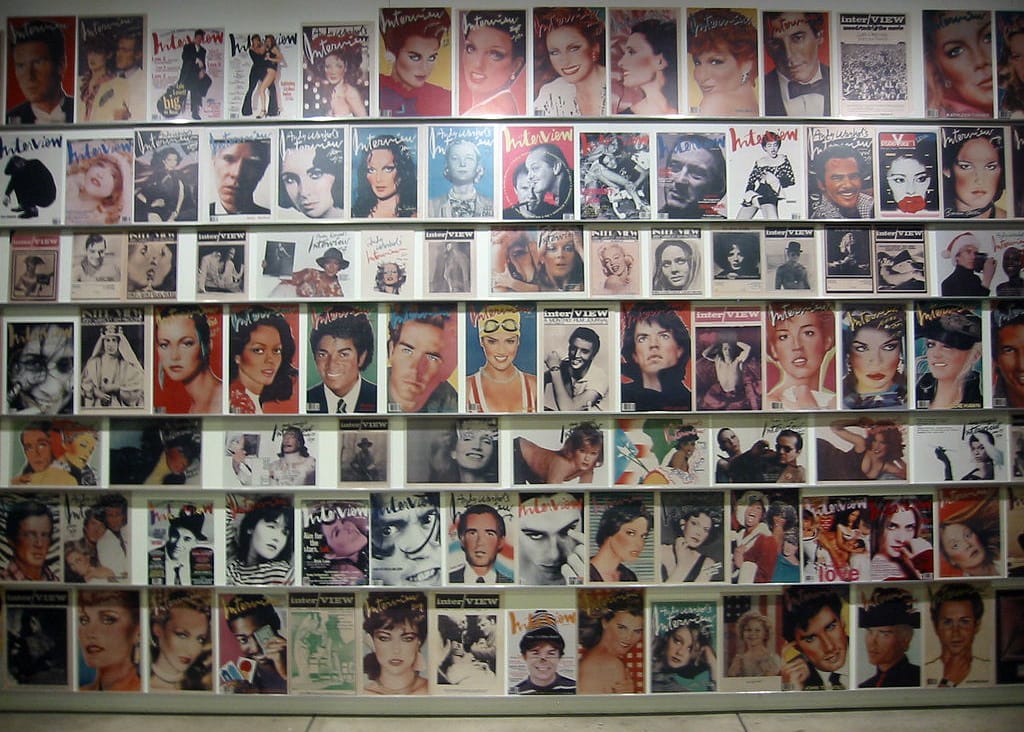

My personal experience of her does not match the personal notes given above. When I was an intern an Interview in the autumn of 1997 all of the junior staff lived in fear of her and scuttled to fulfill her demands or get out of her way when she was in a mood. She quite often seemed to be in a mood. I may have spoken to her once in response to her asking me a question. I don’t recall how I responded or whether my answer was sufficient. She stalked off upon getting it. At the time, working at Interview appeared to me to be utterly repellent.

My anecdote should not injure her reputation or make her any less compelling. The creation of fables around dead cultural figures infantilizes us, encourage us to simplistically divide up the world into the saints and the sinners, instead of seeing ourselves as creatures stamped with a faltering humanity that is, nevertheless, occasionally transcendent. The worship of heroism and preternatural ability has generated in us a mean-spirited and profligate envy that looks to tear down our idolized characterizations almost immediately upon building them up. What if Sischy was at that time in her life a mean, mercurial presence who was unhappy with her work situation and didn’t mind making people feel small? What if we gave an even-handed and nuanced accounting of the people we treasure? We might be more able to look at our own lives with greater integrity.