How White Elites Drained Ancient Art of Its Color

The publication of “Chroma” represents an important shift by museums toward recognizing polychromy and its entanglement with white supremacy.

In the autumn of 2022, Max and I walked up the iconic steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City to visit Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color. As the young son of a professional classicist, and a burgeoning one himself, my museum partner already knew about the ancient history of painted statues when we began to explore the galleries. Max’s knowledge seemed the exception rather than the rule. During our tour of the exhibition, as we wove between ancient works and their modern polychromatic restorations, we came across parents and children transfixed in front of these colorful re-imaginings — and, by the look of it, the parents’ reactions ranged from disbelief to intrigue to disgust.

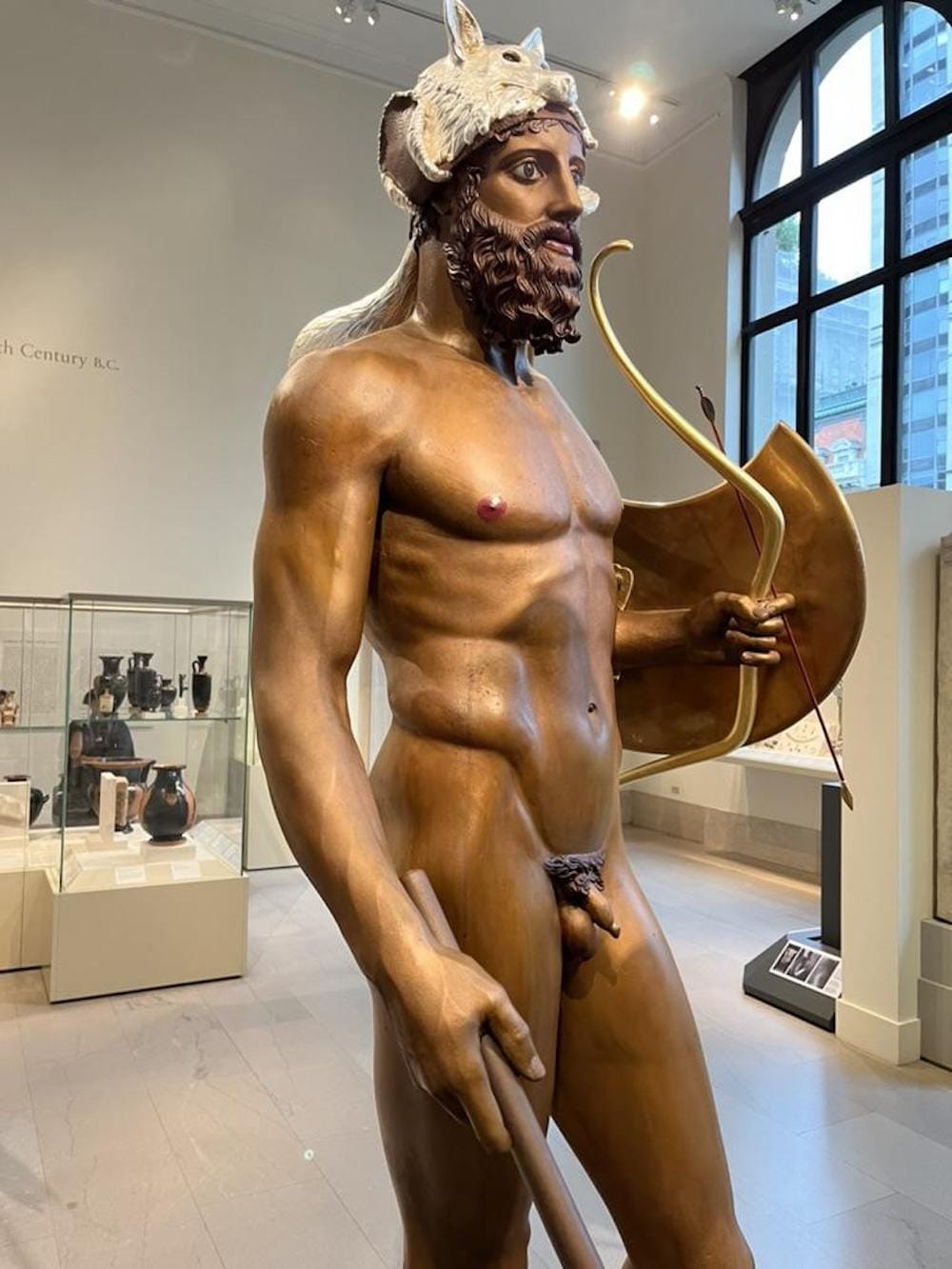

“It looks so, well, tacky,” stammered one woman. “They could not possibly have been this gauche,” commented a man in a suit and tie. While the adults looked stunned, the children alongside them appeared more curious and accepting of the colorful reconstructions. The young came in with less baggage, fewer preconceptions about what classical art should look like. While Max and I marveled at scarlet droplets of blood oozing from the ears of the Quirinal Boxer and took in the vivid chevrons on the leggings of a painted archer, many adult visitors almost seemed to be grieving what they thought they knew about the past in light of what they were seeing.

Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color ran at The Met from the summer of 2022 to the spring of 2023. The exhibition explored the remnants of polychromy (the Greek word for “many colors”) on ancient artworks from the museum’s collection and beyond, and highlighted the efforts of classical archaeologists Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, who have spent more than four decades reconstructing Greco-Roman painted artworks. It also unveiled the museum’s Archaic-era Sphinx finial, newly reconstructed by the team from Liebieghaus in Germany and The Met.

Chroma: Sculpture in Color from Antiquity to Today provides an overview and analysis of this epic exhibition in print. Dozens of color illustrations help bring this technicolor world back to life, along with 23 chapters from 38 scholars. The book also expands beyond the exhibition’s largely Greco-Roman scope, incorporating North America into its geographic range and briefly examining polychromy in cultures from Mexico.

A two-day scholarly symposium held by The Met in March of 2023 forms the foundation of Chroma. In their introduction, Met curators Séan Hemingway and Sarah Lepinski provide an overview of the exhibition, and the broader field, covering the discovery and reconstruction of ancient polychromy, along with its history in sculpture from antiquity to the Renaissance, and the reception of ancient polychromy in museums today.

The chapters within Chroma range from technical to qualitative, making it approachable for both specialists and casual readers. Along with investigating scientific and digital approaches for recovering polychromy on ancient artworks, like 3D imaging or X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF), the early chapters look at the history and present state of this work. The Brinkmanns’ choice to create physical rather than solely digital reconstructions is an important one. Museum audiences can only begin to full understand the tactility and impact of an artwork when they can see it reproduced in the round. Polychromy experts including Mark B. Abbe and Adriana Rizzo look at the remaining pigment on the Princeton Alexander from Hermopolis Magna in Egypt, while Erin A. Peters addresses the Temple of Dendur. Chapters on “Color in Mexica (Aztec) Sculpture” and Renaissance Europe are also engaging and avoid technical jargon.

Chroma’s contributors do a good job of opening the more specialized aspects to general audiences, but what most sets it apart from similar volumes is its attention to sociopolitical factors. Several chapters address the complexity of race in polychromy. In a particularly timely essay, Najee Olya confronts race through the lens of the skin colors Greeks and Romans chose for artworks depicting what they called Aithiopes or Aethiopians. As Olya notes, the modern state of Ethiopia is not equivalent to the Greek imagining of Aethiopia, yet modern notions of racial categories often appear on museum labels used today to frame these objects.

Sinclair Bell speaks directly to the problem of historical anachronism in his chapter on Aethiopians in Roman sculpture, noting how “casually seductive it can be to import modern notions of ethnicity or race into our picture of antiquity.” Romans or Greeks were not without ethnic bias, or what we might call proto-racial notions — classicists like Jackie Murray have pointed out the “racecrafting” at work in Greco-Roman antiquity — but our modern definitions of race and space do not map directly onto the ancient Mediterranean past.

One theme that stands out throughout Chroma is the museum’s responsibility to both the public and the past. Shiyanthi Thavapalan, an expert on color in ancient Mesopotamia, points out how important it is to recognize the museum’s authoritative role in “curating the public’s consciousness about the past.” As she notes in her pivotal chapter, “Museum displays do not reveal or merely transmit objective truths but rather create knowledge about science, culture, and history.” Thavapalan asks museum personnel to be more transparent in labeling reconstructions, to make clear that these narratives are suggestions rather than facts and they reflect a specific moment in time. These representations mark our evolving knowledge of color in the ancient world, so the year they were made matters, whether it’s the 1990s, the 2000s, or today. They are often educated guesses rather than 1:1 representations of what ancient viewers saw.

The publication of Chroma represents an important shift on the part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art toward recognizing polychromy and its entanglement with white supremacy. In 2019, the museum allowed for parts of its galleries to be displayed in “White at the Museum,” a segment on the television series Full Frontal with Samantha Bee. Now, the book’s 40 contributors should take center stage on the issue of polychromy moving forward. As the volume indicates, there is still a need to speak to the broader public about the significance of ancient race, class, ethnicity, gendered colors, and status discussed within. As Bell notes in his chapter, the Chroma exhibition and book help to dispel the “myth of whiteness in classical sculpture” that still persists.

When I wrote the essay “Why We Need to Start Seeing the Classical World in Color,” in 2017, I was neither the first nor the last academic to speak about the history of polychromy. Years prior, Princeton historian Nell Irvin Painter began discussing chromophobia and racism tied to our modern worship of white marble. But I was one of the few classicists writing about academic issues for the wider public. For decades now, the Brinkmanns have provided physical representations of polychromatic works that serve to combat early modern European romances about the whiteness of the classical past, but Chroma brings together image and analysis in an important volume.

In the nine years since my essay, predominantly White museum-goers have griped about what they perceive as the garish appearance of polychromatic reconstructions, emailing me directly or, at times, speaking to each other in museums. Their comments resonate with burlesque dancer Jo Weldon’s remark that the critical construction of “tackiness” is often cultivated by elites as a way to signal their own supremacy within a culture. Trump’s continued maintenance of the “purity” of neoclassical architecture for federal buildings or Elon Musk’s recent criticism of Lupita Nyong’o’s likely casting as Helen of Troy in Christopher Nolan’s forthcoming adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey are examples of how White elites continue to serve as gatekeepers and perpetuate the pseudo-whiteness of antiquity. This is all part and parcel of the ways we instruct the next generation on how to view a past — one that is, in this case, increasingly redacted, rewritten, and purged of people of color once again.

Chroma successfully demonstrates that color was not viewed as inelegant or uncouth in the ancient world. Both the exhibition and the volume illustrate that the ancient world was filled with diverse groups of people of varied skin tones creating artworks that reflected this spectrum of shades. The continued struggle to shift public opinion of polychromy and increase knowledge about the diversity of the ancient Mediterranean will take more than an exhibition or a catalog, but this book is a crucial step in transforming “tacky” into beauty — and exposing the next generation to the realities of a more polychromatic, multicultural, and complex past.

Chroma: Sculpture in Color from Antiquity to Today (2025), edited by Seán Hemingway, Sarah Lepinski, and Vinzenz Brinkmann is published by Yale University Press and is available online and in bookstores.