Hyperrealism Meets Queer Futurism at NADA Miami

The strongest booths at the fair suggested that the future is seeping into the present and that mundane objects can carry the weight of worlds.

MIAMI — The strongest booths at this year’s NADA Miami returned to two persistent ideas: that the future, particularly queer and ecological, is already seeping into the present and that the mundane objects around us, such as light switches, social security cards, our pets, and plants, can carry the emotional and political weight of entire worlds. Nowhere was this clearer than in Miami painter Thomas Bils’s photorealistic works at Baker-Hall Gallery, in which precision and intimacy converge with existential dread. His painting “Phone Wallet Keys” (2025), depicting a social security card, won the coveted Pérez Prize acquisition, marking the first time the museum selected a work from a local NADA presentation.

Bils, who grew up in Central Florida, treats hyper-specific details as the points where everyday life cracks open, and the latent emotions are exposed. “The less I think about why something interests me, the better,” he told Hyperallergic.

“Phone Wallet Keys” exemplifies how a government document can be elevated to devotional status, a symbol of both the power and fragility of bureaucratic identity. At a moment when American identity and citizenship feel increasingly precarious, when the meaning of “security” itself is under political siege, the painting reads as a quiet expression of panic: What does it mean to hold a social security card anymore, or to believe in the promise of protection it once implied?

Hyperrealism becomes surrealism the moment you realize you are studying not the object, but rather the anxiety it carries.

Other paintings, like “Civilization Starter Kit” (2025), featuring a doorway-height light switch, operate similarly. They begin as jokes about scale or childhood hiding places, then slowly reveal themselves as meditations on the unstable infrastructure of everyday life.

If Bils’s work suggests a destabilized present, several of the fair’s most compelling booths took the next step, imagining queer, ecological, and ancestral futures emerging from that instability.

No one articulated this shift more vividly than Miami’s Lee Pivnik, whose growing sculpture and photo series, Chimeras, are hybrid creatures adapted for a Florida that feels increasingly unlivable. This year’s new addition, the coyote chimera, reflects a species that has migrated stealthily into Miami’s edges in the absence of wolves. Pivnik frames them as archetypes of adaptation: smugglers, scavengers, border-crossers — creatures capable of navigating the state’s political and ecological hostility. His wearable coyote claw sculpture, made of stone crab shells, conch shards, mylar, and fragments of glass, oscillates between drag, costume, weapon, and ritual tool. Photographs of local LGBTQ+ collaborators wearing the pieces extend the work into community storytelling of Miami’s queer future.

“A lot of what we talk about on the shoot is how fucked Florida is,” Pivnik said. The future he proposes isn’t utopian; it’s resourceful, collective, and feral.

Continuing the focus on animal symbolism, Debbie Lawson’s sculptural alligator, at Sargent Daughters, appears to have morphed into a carpet, almost like a relief sculpture. Lawson, known for heraldic animals tied to British iconography, wanted her first presentation in Miami to speak directly to the “local ecosystem and the animals iconic to this space.” The alligator deliberately grounds her textile-based practice in South Florida’s environmental reality. In Miami, the alligator is a keystone species whose labor is constant and often invisible: sculpting wetlands, regulating water flow, and creating “gator holes” that become life-sustaining refuges for birds, fish, and mammals during drought. Lawson’s alligator, emerging from a Persian runner like a survivor rising from a buried history of colonial trade, becomes an emblem of the ecological endurance that undergirds life here.

In a different register, Los Angeles-based Maddy Inez approached futurity through ancestry, ecology, and fire. Her Fire Follower series draws from California plants that bloom only after wildfires — Phacelia, Fire Poppy, Whispering Bells. These serve as metaphors for the knowledge systems that resurface after attempted erasure.

“Who decides what the best way to care for land is when colonization erased the people who held the knowledge to do so?” Inez asks in a press release.

Her clay forms with veined petals, blooming from imagined ash, carry the matrilineal lineage of her mother, Alison Saar, and grandmother, Betye Saar. The work reads as both remembrance and prophecy: a ceremony for the future rooted in ancestral fire.

Speculation expanded to planetary scale at Foundry Seoul, which presented a two-person installation by Omyo Cho and Hyunhee Doh. Cho’s aluminum and resin structures propose that organic life forms evolved to withstand climate-altered worlds. In the hanging sculpture "Nu Vein" (2025), petals unfurl like a “moment of flowering” that the artist describes as a visualization of connection and adaptation. The forms look both biological and technological: shimmering, hybrid organisms that suggest what life might become when forced to reinvent itself under environmental pressure.

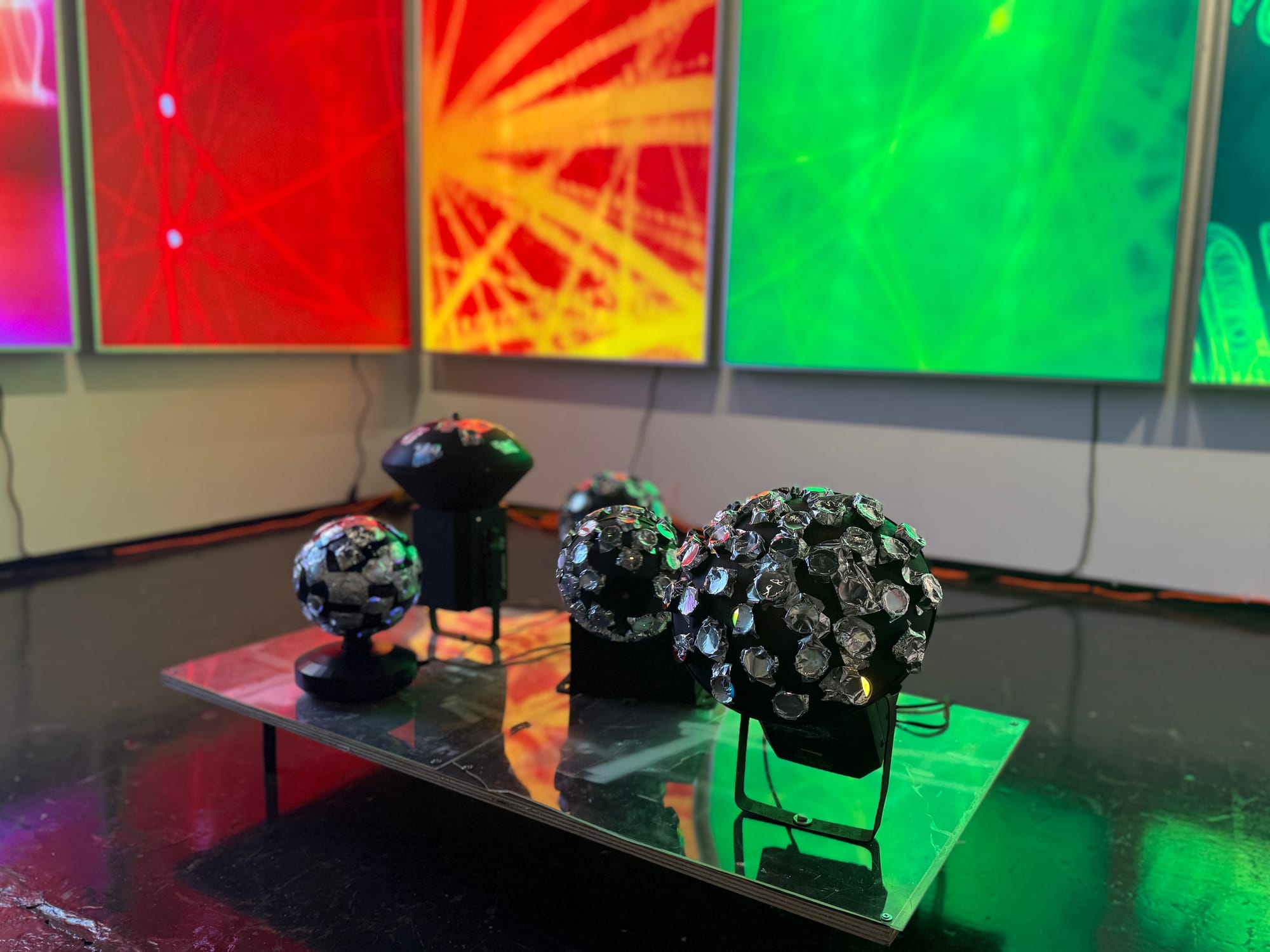

Hawkins Headquarters offered a more barren vision. Atlanta-based photographer Jackson Markovic’s ongoing series Baroque Sunbursts comprised large-scale lightboxes made using a custom photo-positive process that captures nightclub lasers without people and sound. The project emerged after he encountered an abandoned underground Atlanta nightclub with no surviving images due to its illegality; the archive, therefore, had to be invented. At the center of the booth, a kinetic sculpture, “Party 4 U” (2025), which features four rotating disco lights with a pedestal wrapped in aluminum plumbing tape, further strips the club to its mechanical core, and the whir of machines into a durational hum. Its eerie, machinic stillness suggests a future in which nightlife persists only as an afterimage.

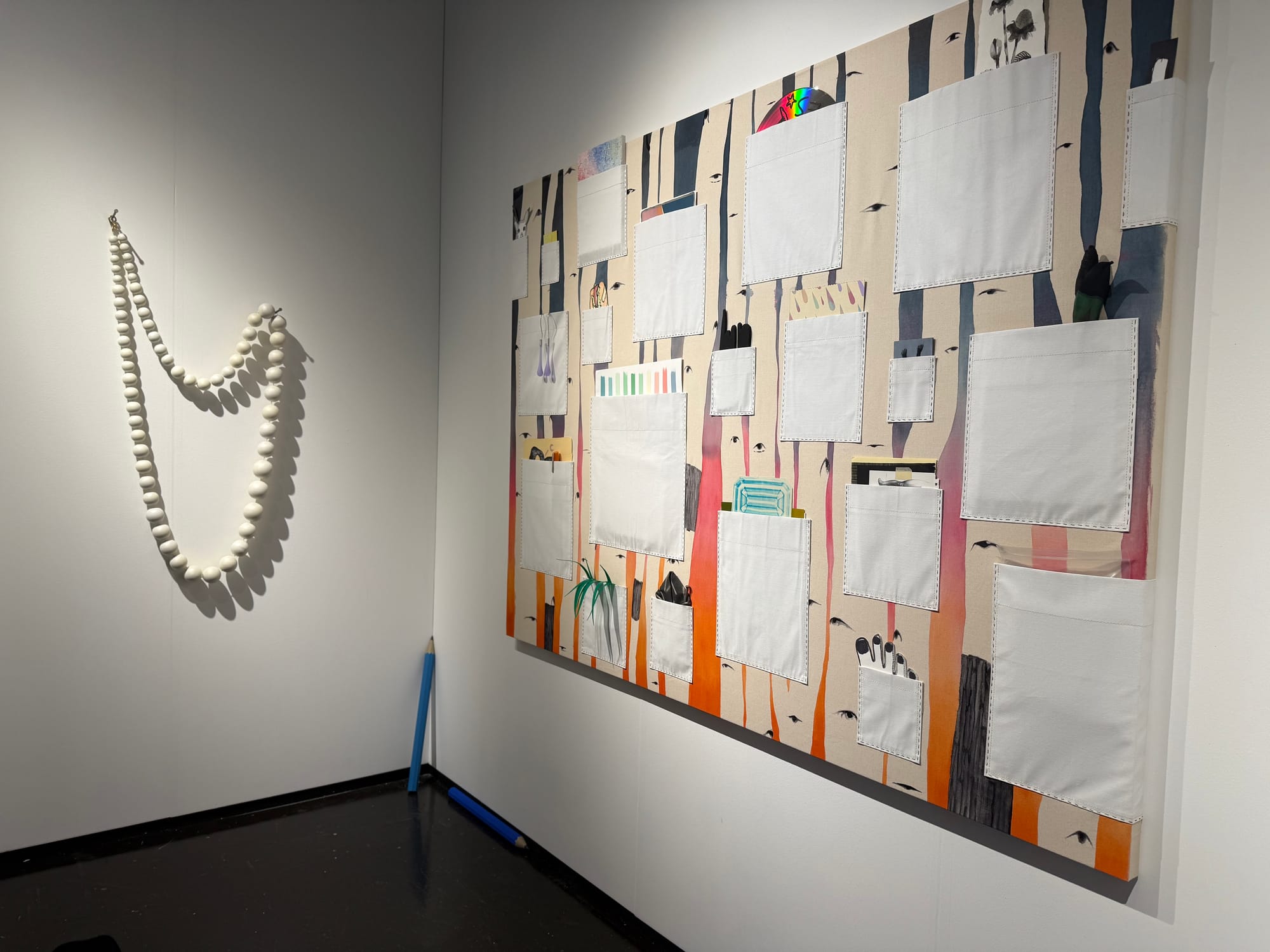

For Sheet Cake Gallery x Burnaway, Claire Torina expanded the fair’s fascination with the seemingly mundane and with scale by constructing a miniature gallery within the booth that housed her objects of devotion. Torina shrinks her world to a level of disarming intimacy then punctuates it with comically oversized objects. A giant golf pencil, an enormous pearl necklace (“Grave Goods,”2025), and repurposed paint swatches (“Little Legend,” 2025), referencing Leonard Horowitz’s preservationist murals in Miami, destabilize the viewer’s sense of proportion much like Bils’s hyperrealism. In a fair immersed in speculative worlds, Torina’s booth offered an altar to the domestic as surreal and the tiny as monumental.

Across the fair, artists returned to the question Bils’s painting raises: What does it mean to hold onto identity when the world itself feels unstable? Hyperrealism, in the artist’s hands, becomes a form of witnessing, while queer futurism, in Pivnik’s and Inez’s work, becomes a strategy for survival. At NADA Miami, the objects asked how we imagine what comes next.