The Cultural Legacy of Animals in Japanese Art Over 17 Centuries

With more than 300 works drawn from 66 Japanese institutions and 30 American collections, this is likely one of the largest exhibitions of Japanese art that a generation of Americans will ever see.

WASHINGTON, D.C. — With more than 300 works drawn from 66 Japanese institutions and 30 American collections, the National Gallery of Art has had its hands full during the summer. So full, in fact, that The Life of Animals in Japanese Art received a makeover halfway through its run switching out 47 works for 40 new pieces. (“Out with the horses, in with the tigers,” announced the Washington Post.)

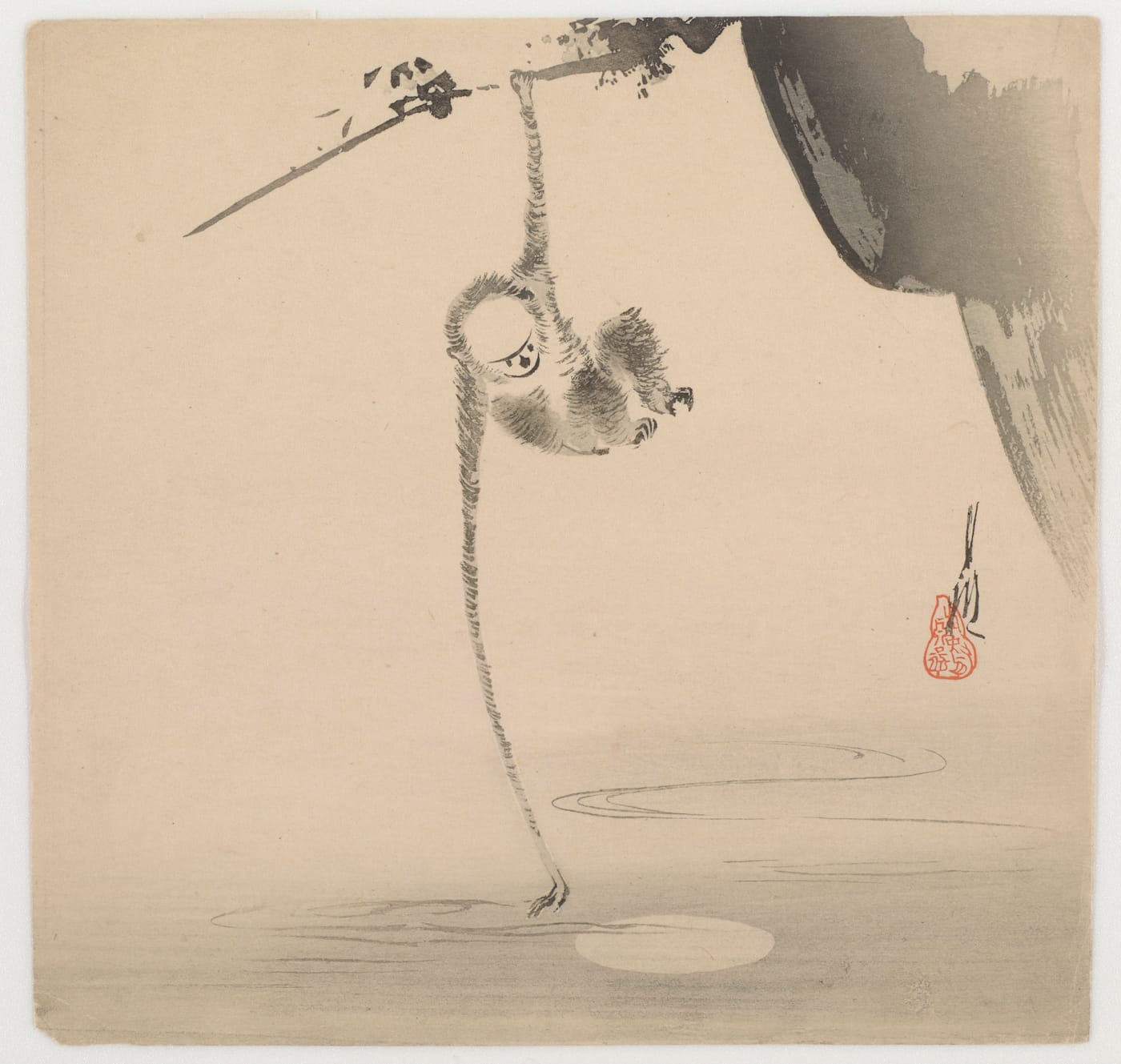

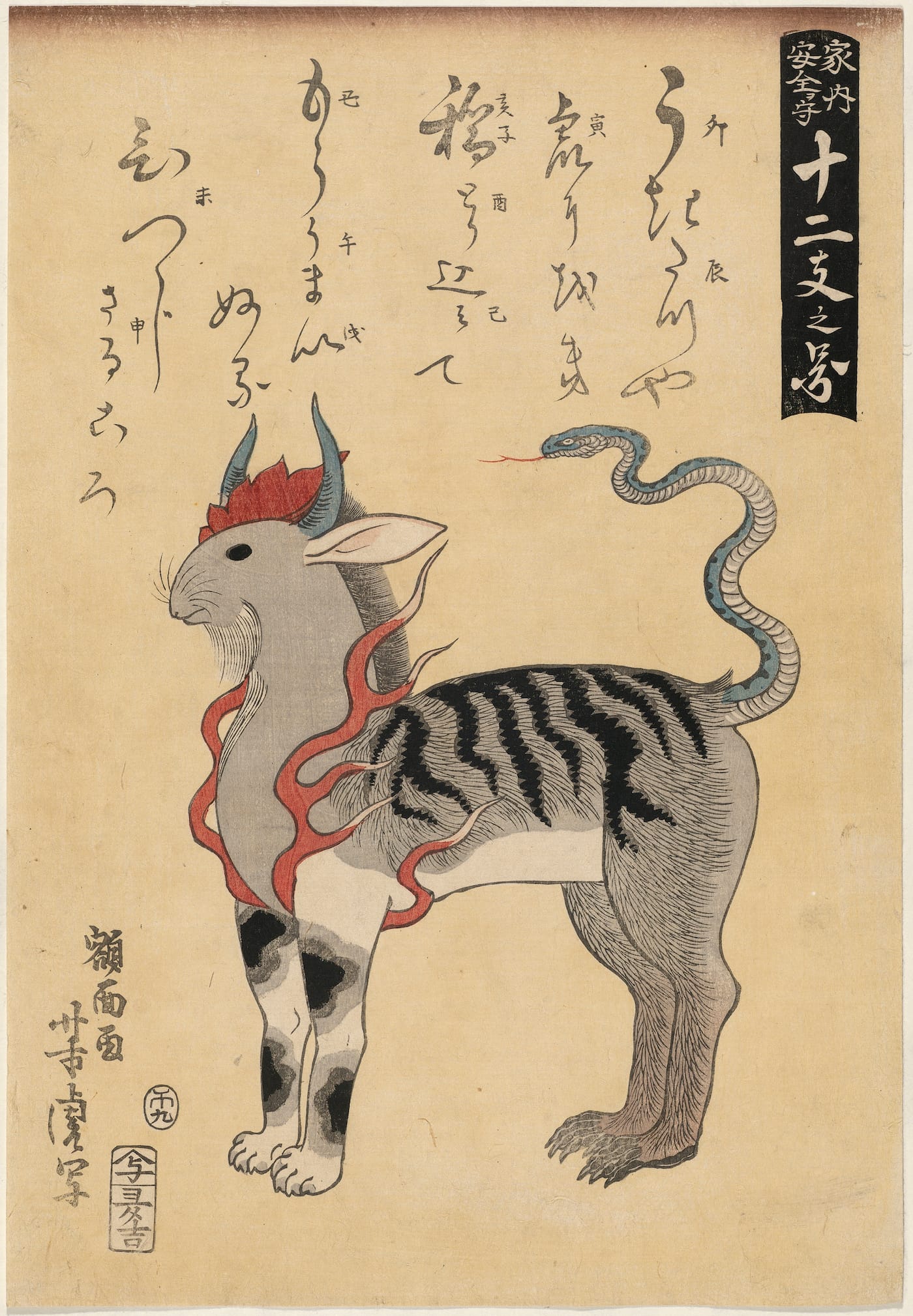

The exhibition, which closes August 18, is one of the largest shows ever displayed at the museum, and includes sculptures, paintings, lacquerworks, ceramics, metalworks, textiles, and the woodblock prints. The collection is a magnificent, vibrant illustration of Japanese culture spanning 17 centuries of history. Many of the nearly 180 works traveling from Japan are also masterpieces, which rarely — if ever — leave the country.

Animals have coexisted with the Japanese people for most of the civilization’s existence. Shintoism, a native religion which became popular around the sixth century, involved the worship of divine powers manifested in nature. Animals like deer and foxes were considered spirit messengers while others like horses and monkeys functioned as representations of deities. The cultural diffusion between Buddhist and Shinto beliefs also resulted in a mashup of aesthetic traditions. Japanese artists also soon adopted the East Asian zodiac system, incorporating its cycle of 12 animals into its traditional aesthetic program.

A major feature of this exhibition is the strong presence of woman artists, many of whom have been previously overlooked. Ōtagaki Rengetsu, a Buddhist nun from the Edo period, is said to have changed her Kyoto residence several times to escape her followers, who would line up outside her home hoping to commission a personal painting, poem, or one of her popular hanging scrolls.

Animals also featured heavily in depictions of Japanese samurai, who were required to master archery, swordsmanship, horseback riding, and other skills of the warrior class. Oftentimes, animals would be incorporated into the often violent and intimidating (if also, perhaps, slightly playful) samurai helmets and armor.

The exhibition’s later galleries exemplify how animals have endured as potent symbols of Japanese culture for years, gradually changing alongside the country. (The arrival of Europeans in the late 1500s and the industrialization of the mid-1900s are two such examples.) And interspersed throughout the show are contemporary artworks that tie the narrative together, demonstrating how a 14th-century “Deer Bearing Symbols of the Kasuga Deities” might have inspired Nawa Kohei’s 2015 “PixCell-Bambi #14.”

Cats and dogs, carp and cranes, elephants and rice. The carefully considered and elegant installation at the National Gallery hones in on how animals became a prevailing force in Japanese art. Traditional kimonos dance with designs of seashells, birds, and tassels. Newer ones include commentary on the changing notion of Japanese identity. There are gray factories billowing smoke; another features penguins amid a landscape of tiny icebergs.

There is joy to these juxtapositions of ancient and contemporary, figurative and abstract, gilded and modest. The Life of Animals in Japanese Art rewards close looking, which amplifies the serene exquisiteness of the works on view.

The Life of Animals in Japanese Art continues through August 18 at the National Gallery of Art (Constitution Ave NW, Washington, DC 20565). The exhibition is curated by Robert T. Singer, curator and department head, Japanese art, LACMA, and Masatomo Kawai, director, Chiba City Museum of Art, in consultation with a team of Japanese art historians.