Marketing the Great War

When the United States joined the Allied forces in 1917, the mind of the American citizen was almost as much a battlefield as Europe was.

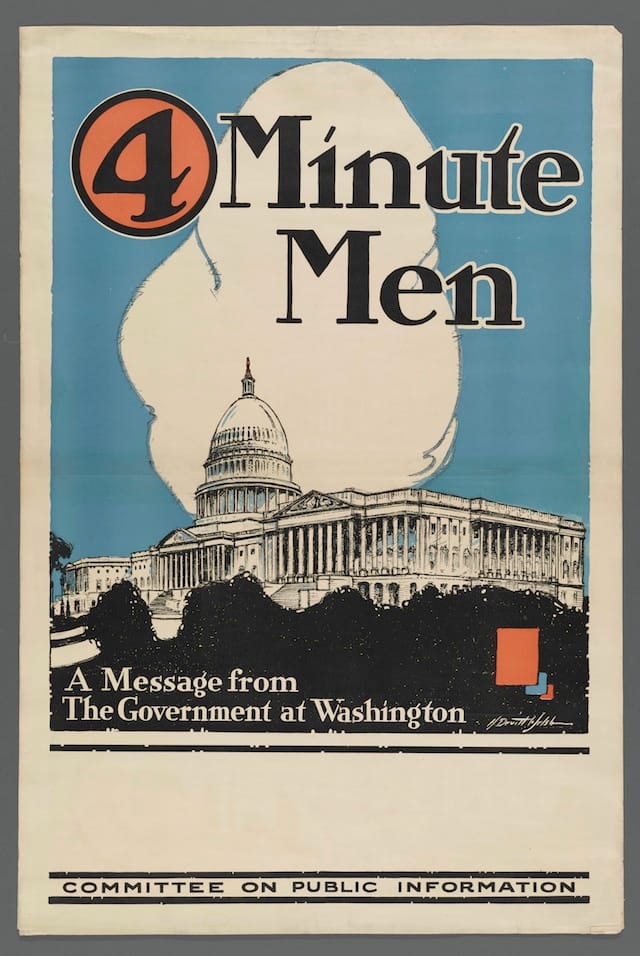

When the United States joined the Allied forces in 1917, the mind of the American citizen was almost as much a battlefield as Europe was. Despite the government’s justification of the war — the fact the German military was sinking American ships and plotting a Mexican take-back of Texas — many citizens felt just as hung-up about their involvement abroad as they do today. So how to convince the doubtful that war is sensible, noble, and patriotic? Queue the propaganda posters, several of which are now on display in the New York Public Library’s latest exhibition, Over Here: WWI and the Fight for the American Mind.

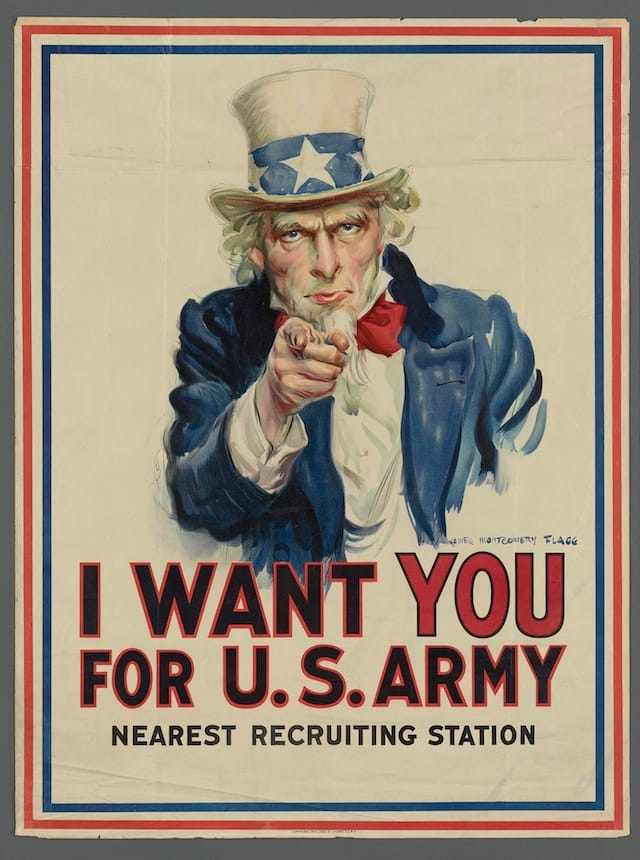

You don’t have to be a World War I aficionado to recognize I Want You for U.S. Army from 1917. In the iconic poster, Uncle Sam stands swathed in red, white and blue, pointing sternly — almost accusingly — at his recruits. Artists may take pleasure in knowing his face is actually a self-portrait of its resourceful artist, James Montgomery Flagg, who copied the pose from a British poster depicting Lord Kitchener. More than four million of Flagg’s posters were plastered in towns across America.

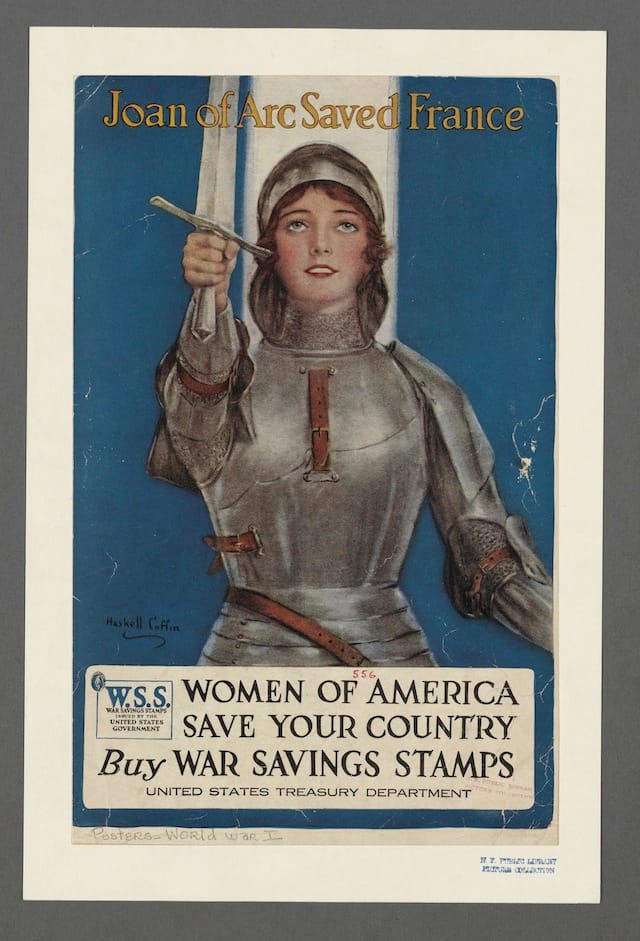

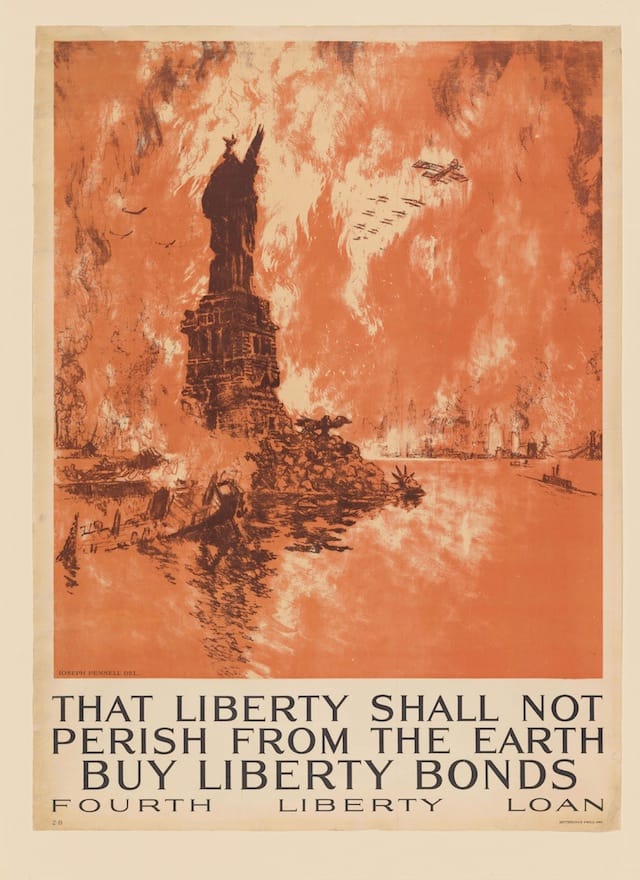

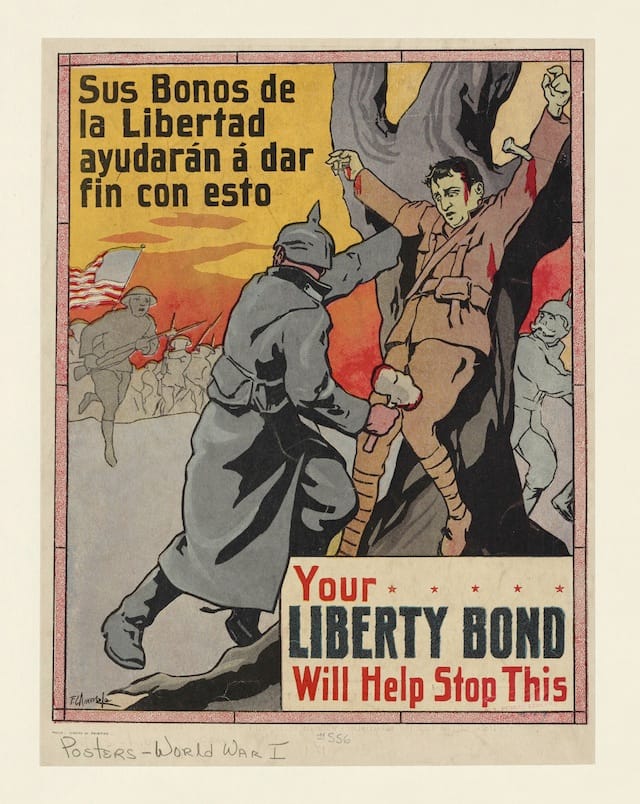

Other posters in the exhibit highlight the importance of securities, which the government smartly dubbed “Liberty Bonds.” Promoted by Treasury Secretary William Gibs McAdoo, Hollywood celebrities, and the Boy Scouts of America, these notes funneled billions of dollars into the war effort. Joseph Pennell’s war bond poster of 1918 suggests buying them will ensure “Liberty Shall Not Perish from the Earth.” Another by F.C. Amorsolo — printed in United States-controlled Manila in 1917 — depicts a Central Power soldier crucifying an allied troop. Spanish text announces, “Your Liberty Bonds Will Help Put an End to This.” And though women couldn’t yet vote, another poster from 1918 urges them to save their country just like Joan of Arc saved France — by buying war savings stamps.

Like all marketing efforts, these were advertisements for a product Americans paid for: 116,516 young men died in the Great War. While freedom certainly comes with a price, scholars still debate over whether the United States should have gotten involved. In the New Republic, Michael Kazin recently argued that America’s involvement in World War I only served to make “that next and far bloodier global conflict more likely.”

Over Here: WWI and the Fight for the American Mind will be on view until Feb. 15, 2015 at the Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III Gallery of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, New York Public Library (Fifth Avenue at 42nd Street, Midtown, Manhattan)