Modernist Camouflage, Reconstructed

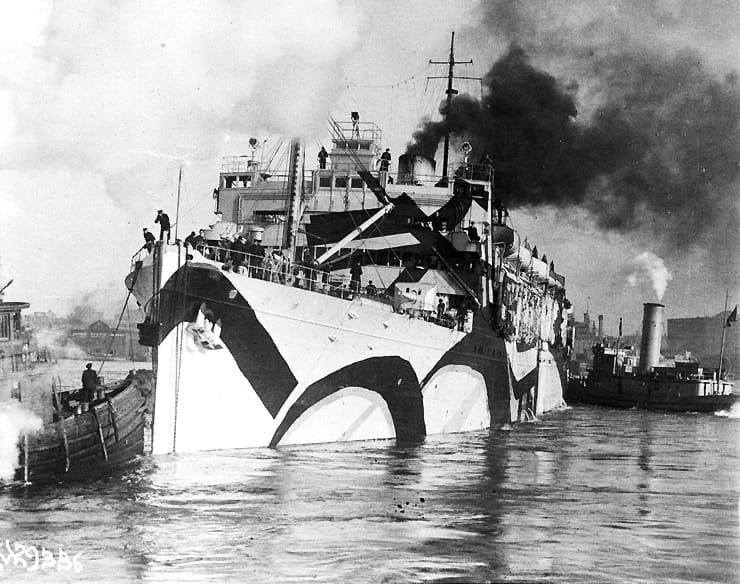

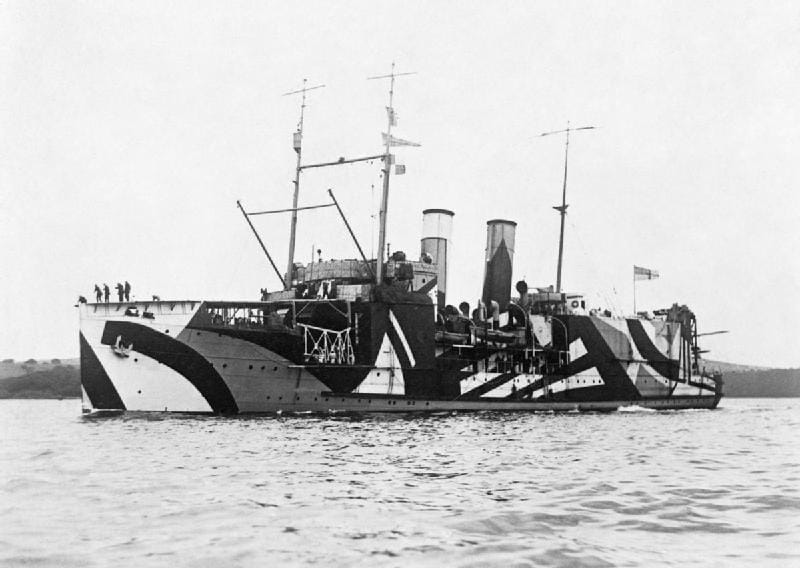

The general goal of camouflage is to be invisible. Back during World War I, however, hundreds of Allied ships went to battle painted in bright geometric designs that were anything but subtle.

The general goal of camouflage is to be invisible. Back during World War I, however, hundreds of Allied ships went to battle painted in bright geometric designs that were anything but subtle. This “dazzle camouflage,” as it was called, was intended to distract and confuse out on the seas, and in a current exhibition at Marc Straus on the Lower East Side, photographer Thomas Bangsted has reimagined this collision between art and war.

Called Mike, the exhibition includes large-scale prints of Bangsted’s painstaking photographs. Each is deceptively simple, seeming like a strange historic capture, yet Bangsted spends up to three years on each piece, layering different exposures into his own reconstruction of time. Everything might seem right for a 1918 wartime photograph down to the vintage rowboat, except the pilot is a guy named Mike hired to pose for just one part of the image.

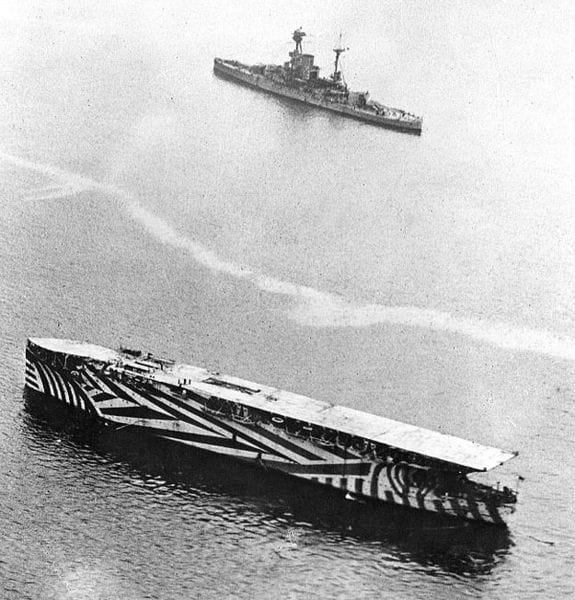

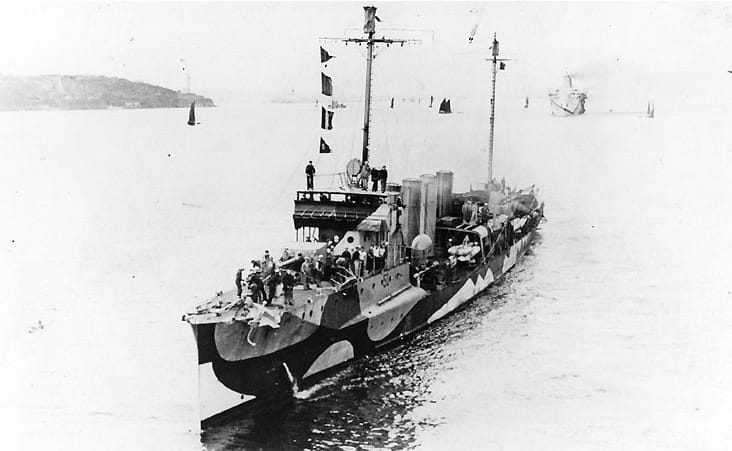

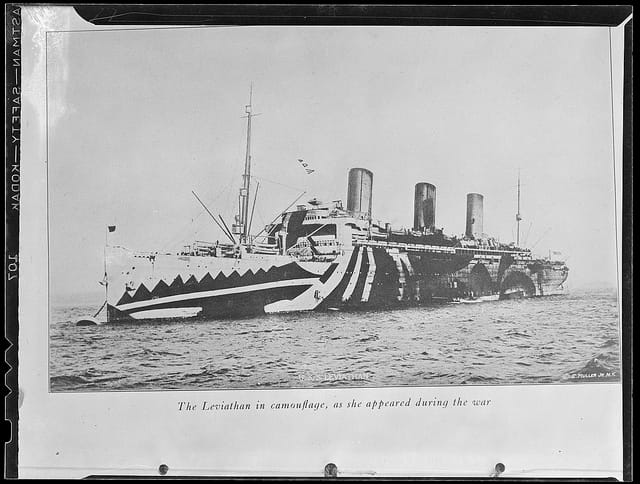

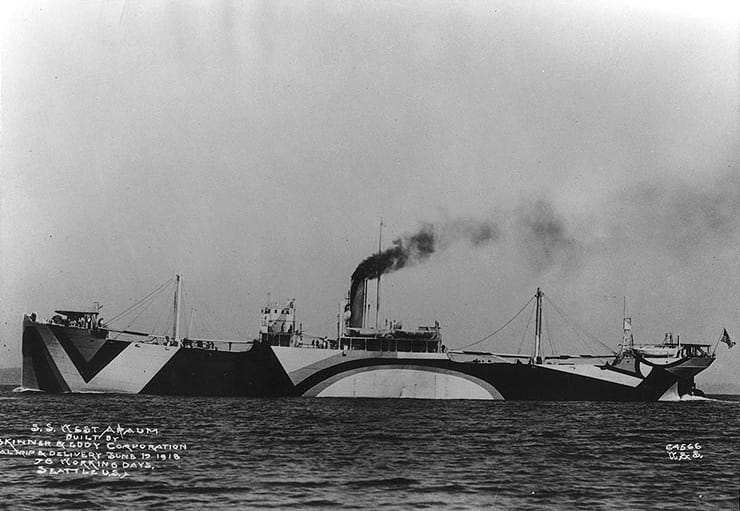

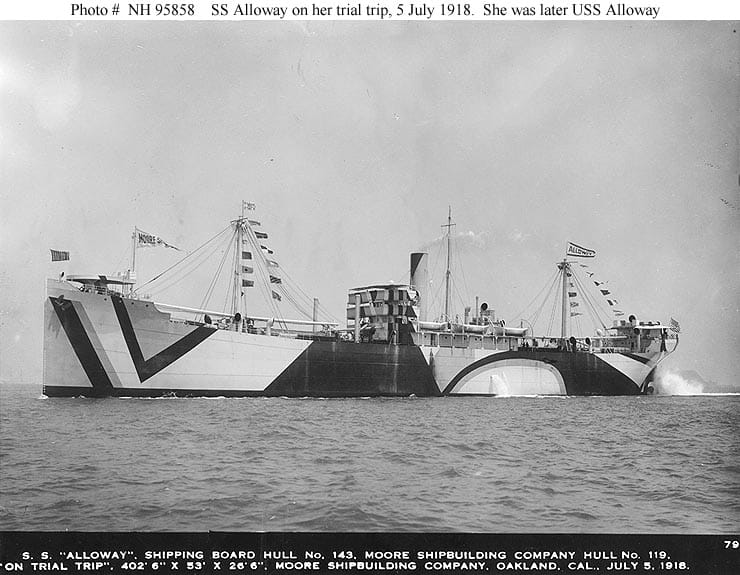

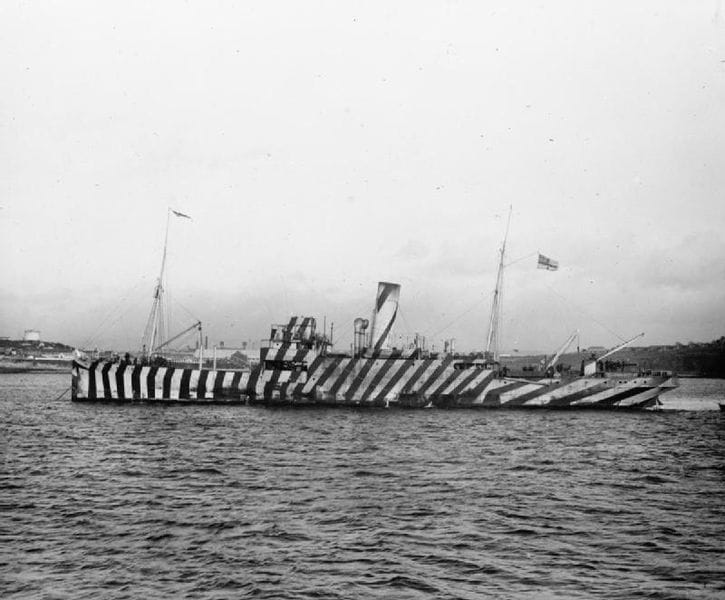

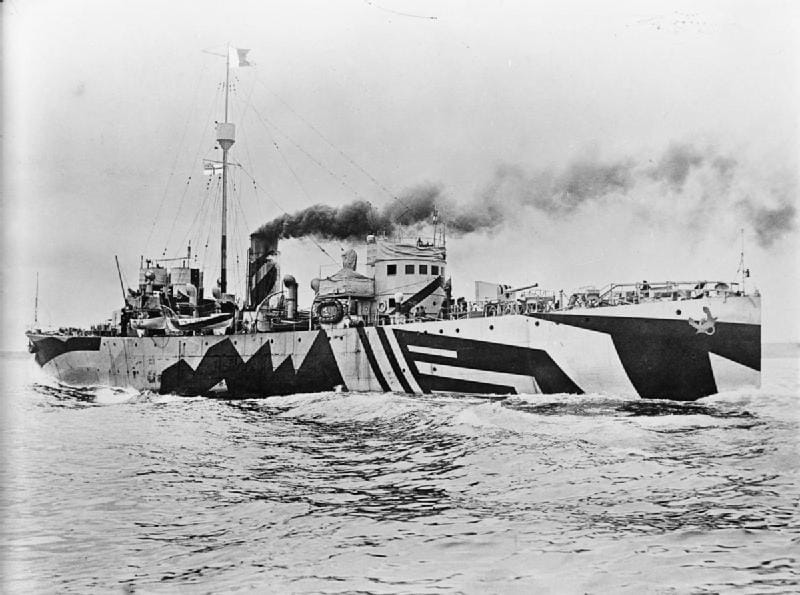

The ships in the photographs date to the World Wars, but Bangsted turned to archives to remake their dazzle camouflage. It’s a stunning creation, as much an artful deception as the strange military strategy it replicates. Old photographs of dazzle camouflage also seem like an impossibility of playful history, sort of like the (also very real) pink British military jeeps. But the camouflage was a serious practice. World War I was a new kind of battle, one where people charging at each other on horses in sometimes garish outfits was replaced with terrifying technology like machine guns, razor wire, and U-boats.

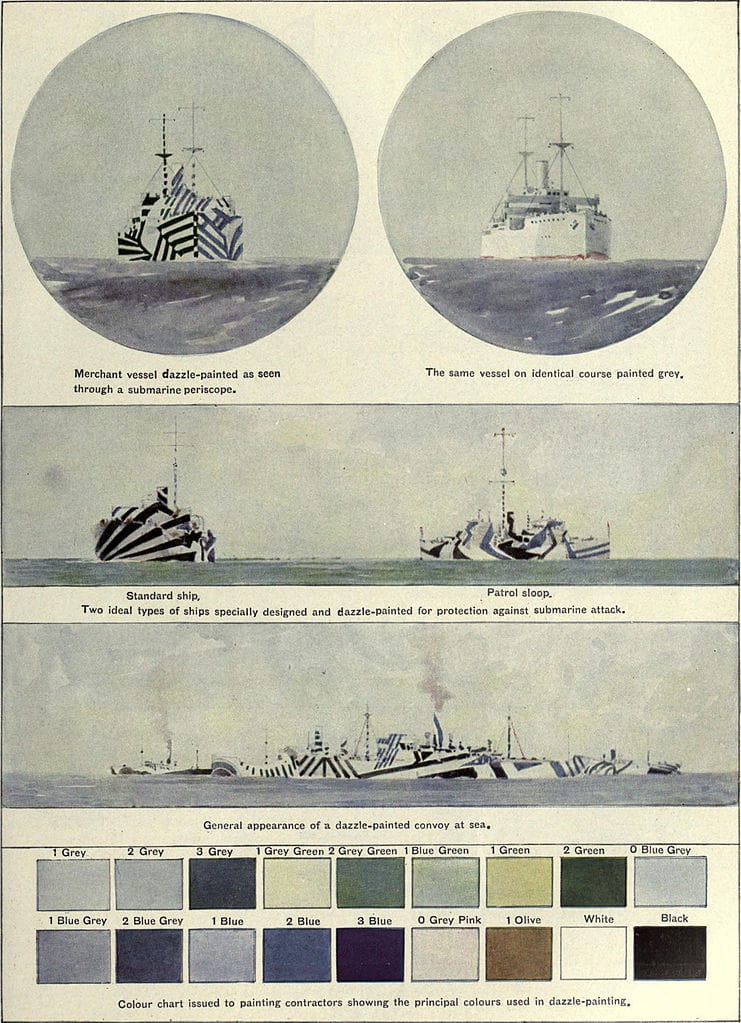

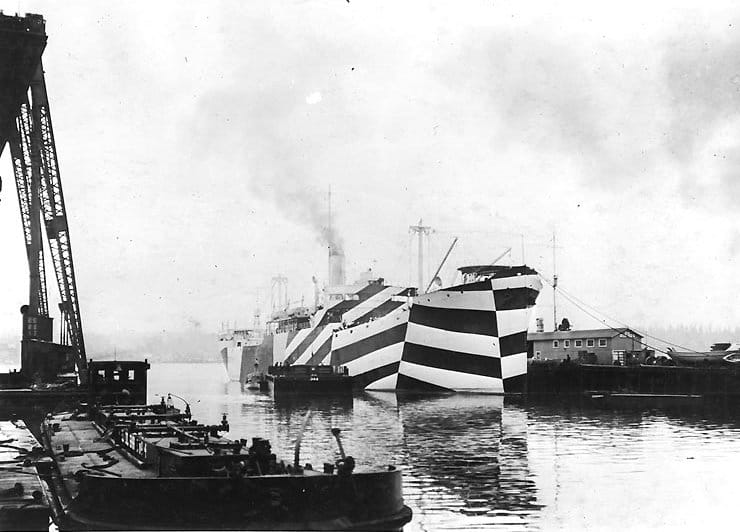

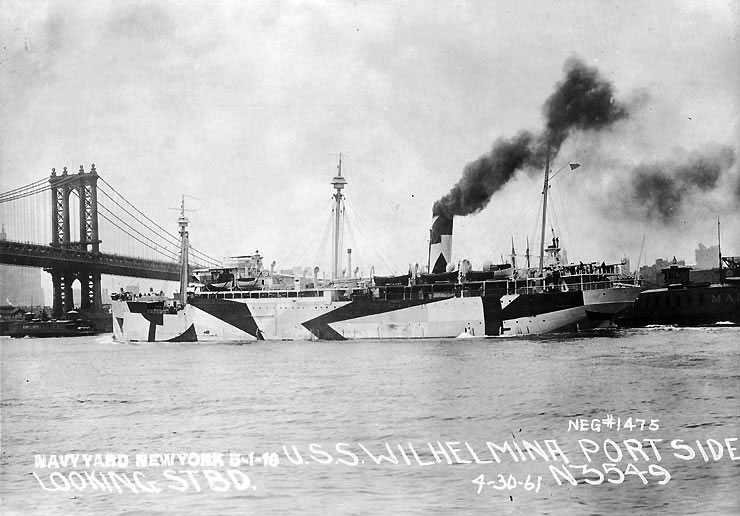

It’s those German submarines that dazzle camouflage was meant to evade. Out on the ocean where both the water and the sky change color constantly, even a drab grey battleship is going to be spotted in some weather. The dazzle approach, rather than try to hide, makes the distance, speed, and direction of the vessel all hard to determine, especially when several ships are together in a dizzying convoy of stripes, checkers, and swirls. And since a U-boat has to aim ahead of the ship for the torpedo to make contact, this illusion could throw them off.

British artist Norman Wilkinson pioneered the idea with the Royal Navy, but he had help from other artists who were conveniently experimenting with Cubism and other forms of abstraction, such as Edward Wadsworth, a major figure in Vorticism defined by its aggressive sharp geometry. While used sporadically during World War II, dazzle camouflage later went out of fashion. As Sam LaGrone at the U.S. Naval Institute explained in an article on dazzle camouflage: “‘Dazzle’ schemes largely faded from use because there was no clear evidence of their effectiveness, especially against technological advances in radar and rangefinders. ‘Dazzle’ was however credited with boosting morale of crews who took pride in the unique and intimidating appearance of their ship.”

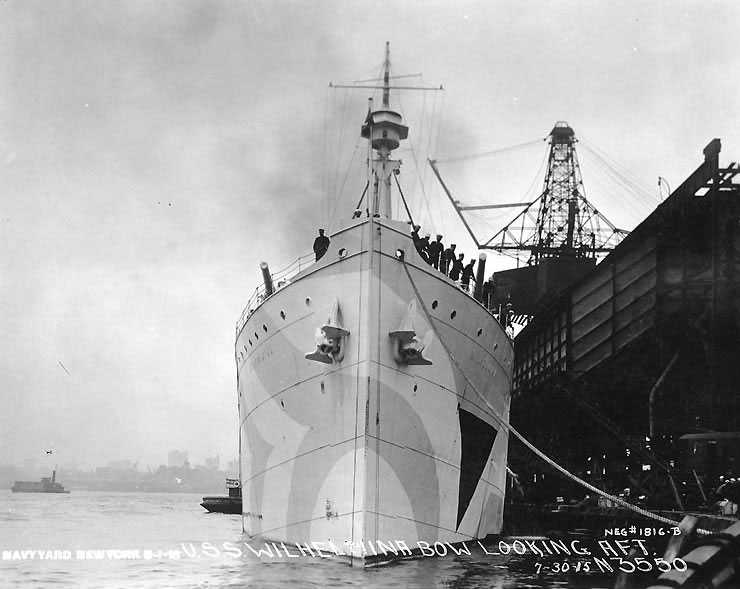

Below are more of Thomas Bangsted’s photographs, as well as historic photographs of the dazzle ships. RISD also has a whole online collection of Dazzle Camouflage plans, showing not just the wild patterns, but the bold colors as well.

Historic photographs of dazzle camouflage:

Thomas Bangsted: Mike continues at Marc Straus Gallery (299 Grand Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan) through February 16.