Munch and Warhol: An Unlikely Pair

Edvard Munch, tortured and brooding; Andy Warhol, detached and impenetrably cool. The two artists might not have gotten along well as studio mates, but as for aficionados of artistic repetition, they have a definite kinship.

Edvard Munch, tortured and brooding; Andy Warhol, detached and impenetrably cool. The two artists might not have gotten along well as studio mates, but as for aficionados of artistic repetition, they have a definite kinship.

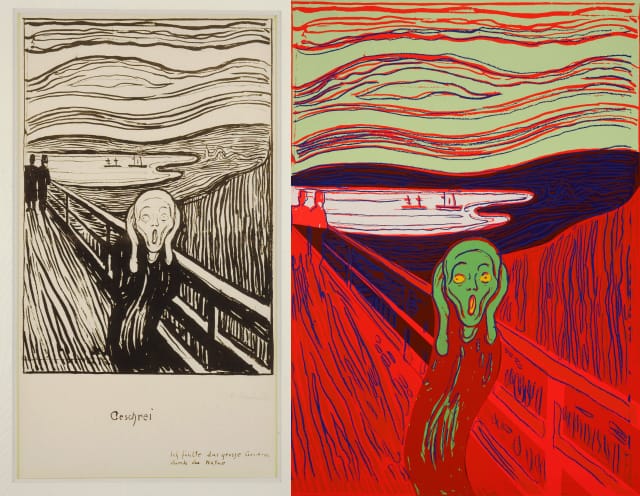

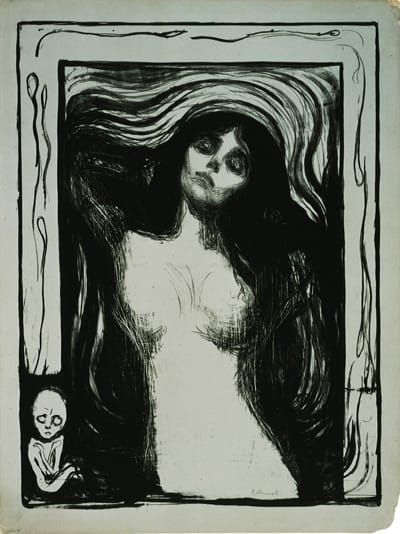

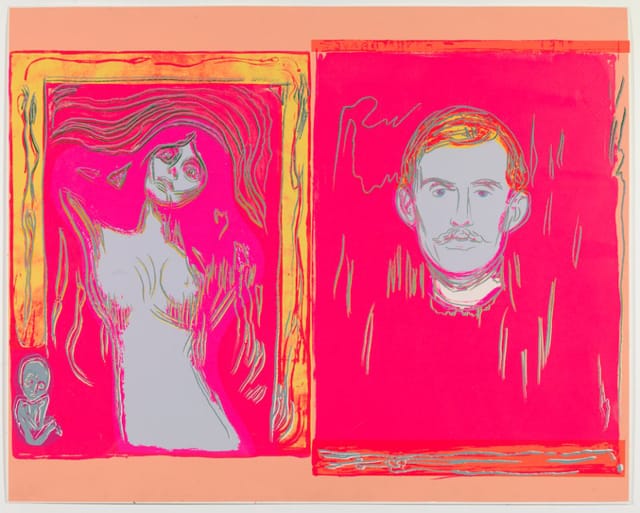

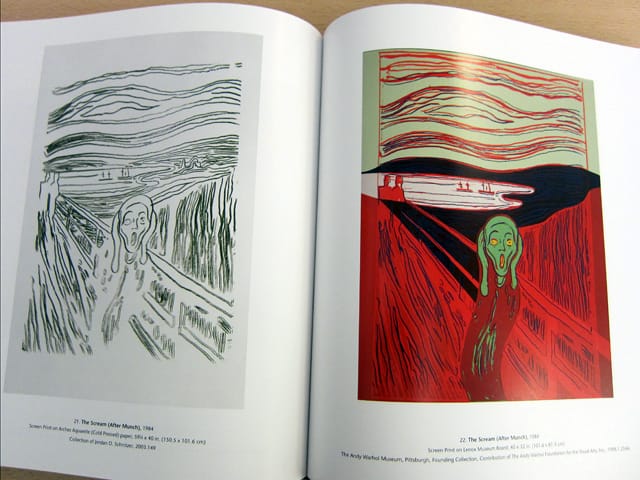

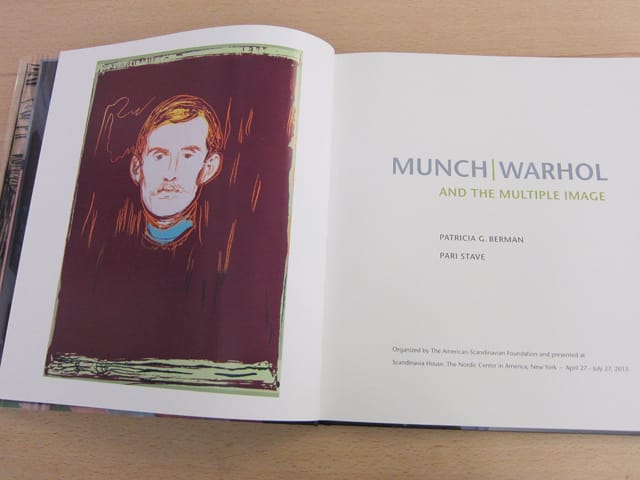

Munch/Warhol and the Multiple Image, an exhibition that just closed at the Scandinavia House, looked at these two artists in their shared use of prints and the repeated image, particularly a 1984 series that Warhol did based on four of his Norwegian predecessor’s subjects. Using “The Scream,” “Madonna,” “The Brooch, Eva Mudocci,” and “Self-Portrait,” Warhol transformed the heavily-lined, dark lithographs of Munch into screen prints drenched in vivid hues. A catalogue by Patricia G. Berman and Pari Stave that accompanied the exhibition presents the whole story, so even though the meeting of the originals and the copies may be over, the surprising link between the two artists can still be explored.

The Warhol prints were all commissioned by the New York–based Galleri Bellman following a Munch exhibition. Of course, appropriation was nothing out of the ordinary for Warhol; that was basically his whole art ethos. He even did duplicative work after Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli.

But Munch is different. As Berman writes in her extensive catalogue essay, “If Warhol offered himself up as surface, Munch was all impenetrable depth.” Yet there is the comparison that they both “lived behind a public mask” — Warhol as the persona as untouchably metallic as his Silver Factory, Munch as “a mediated version of the private self,” who, it could be argued, levied his haunted soul in much the same way Warhol did his gilded one.

As Berman rightly points out, “the resulting prints and paintings have impact precisely because the works of both artists are so well known.” We know Munch’s “The Scream” and Warhol’s Soup Cans not just because they tapped into and have been tapped by consumerism — the former a museum store staple in everything from an inflatable version to finger puppets; the latter a play on American mass-produced icons — but also because the artists themselves appreciated replication as a self-promotional tool. Warhol’s endless screen prints are familiar, and it turns out Munch also used lithographs to drive the visibility of his art and, well, to sell more.

Both artists used the alterations of color to create different moods in each edition, and the repeating prints show how firmly both grasped the power of the image. Warhol commented on this a little when he placed Munch’s self-portrait alongside his “Madonna,” both subject and artist consumed into the clone. Despite Warhol’s cool and Munch’s heavy control of his own persona, there seems to be a lot of anxiety about the meaning of their own art, or the scraping away of meaning as works pass from their original vision into a commodity made by their own hands.

The exhibition and catalogue are the only two New York happenings for the big Munch 150, celebrating 150 years since the artist was born in 1863. Warhol himself had a birthday celebration this week, complete with a gravesite livestream. Obviously, the images they built through repetition and personas are cemented in the public’s memory, and it’s worth examining this meeting between the two, the clash of their art turning a single study of self-duplication.

Munch/Warhol and the Multiple Image was at the Scandinavia House (58 Park Avenue, Midtown, Manhattan) from April 27 to July 27. The catalogue is available online from Artbook and through the shop at Scandinavia House (212/847-9737).