New Histories and Heroes Grace the Walls of NYC's Mayoral Mansion

In 1799, Scottish-American merchant Archibald Gracie built a large house along what's now the northeastern edge of Manhattan.

In 1799, Scottish-American merchant Archibald Gracie built a large house along what’s now the northeastern edge of Manhattan. At the time, what we know as the intersection of 88th Street and East End Avenue was not actually a part of New York City; it was five miles north of the border, and Gracie built his house as a country getaway — “his Hamptons,” in the words of Paul Gunther, executive director of the Gracie Mansion Conservancy.

That same year, the New York State legislature began emancipating the state’s slaves. The process was set in motion with the passage of the Gradual Emancipation Act, but as the name suggests, it was incredibly slow. The act called for the freeing of children born into slavery after July 4, 1799 — but only after they’d worked for their mother’s master for 25–28 years. Anyone who was already a slave when the act was passed would henceforth become an indentured servant, a change in name rather than true status.

These two histories are placed in counterpoint in Windows on the City, the new installation of art and historical objects at Gracie Mansion, which became New York’s mayoral residence in 1942. “I hesitate to call it a show,” said Gunther during a brief media tour last week before the opening. “It’s really …. decorating,” he continued, explaining that while the word has perhaps taken on negative connotations, he thinks of it positively. “Nothing is meant to be permanent; these things are meant to rotate.”

Most of the rotation done for this new installation involved bringing objects into the house, from various institutional collections around the city, rather than removing them from it (although a portrait of Susan Wagner, who initiated the building of a new wing for the mansion in the 1960s, did come down). The emphasis is very much on painting a fuller, more accurate portrait of New York at the turn of the 19th century, which means celebrating not just history written by the victors but history as it was actually lived.

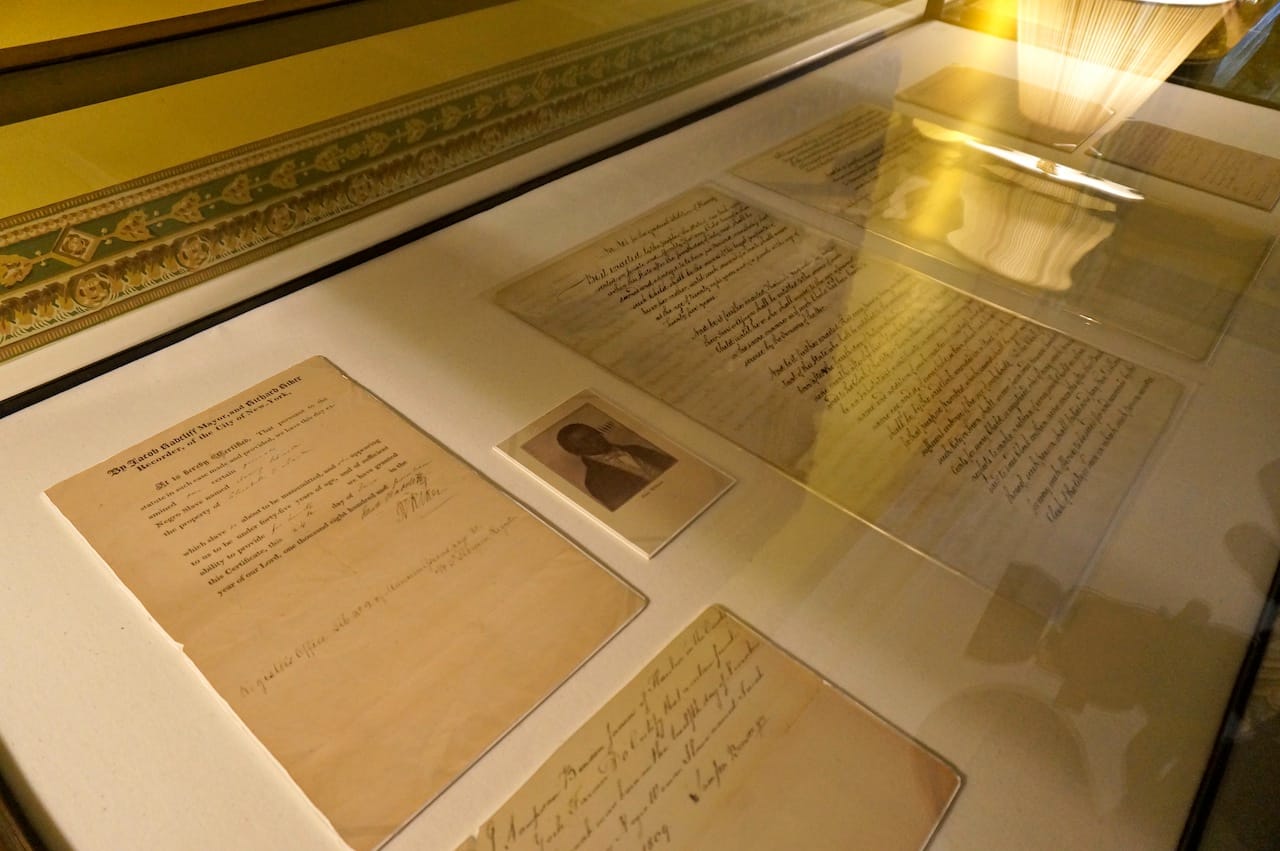

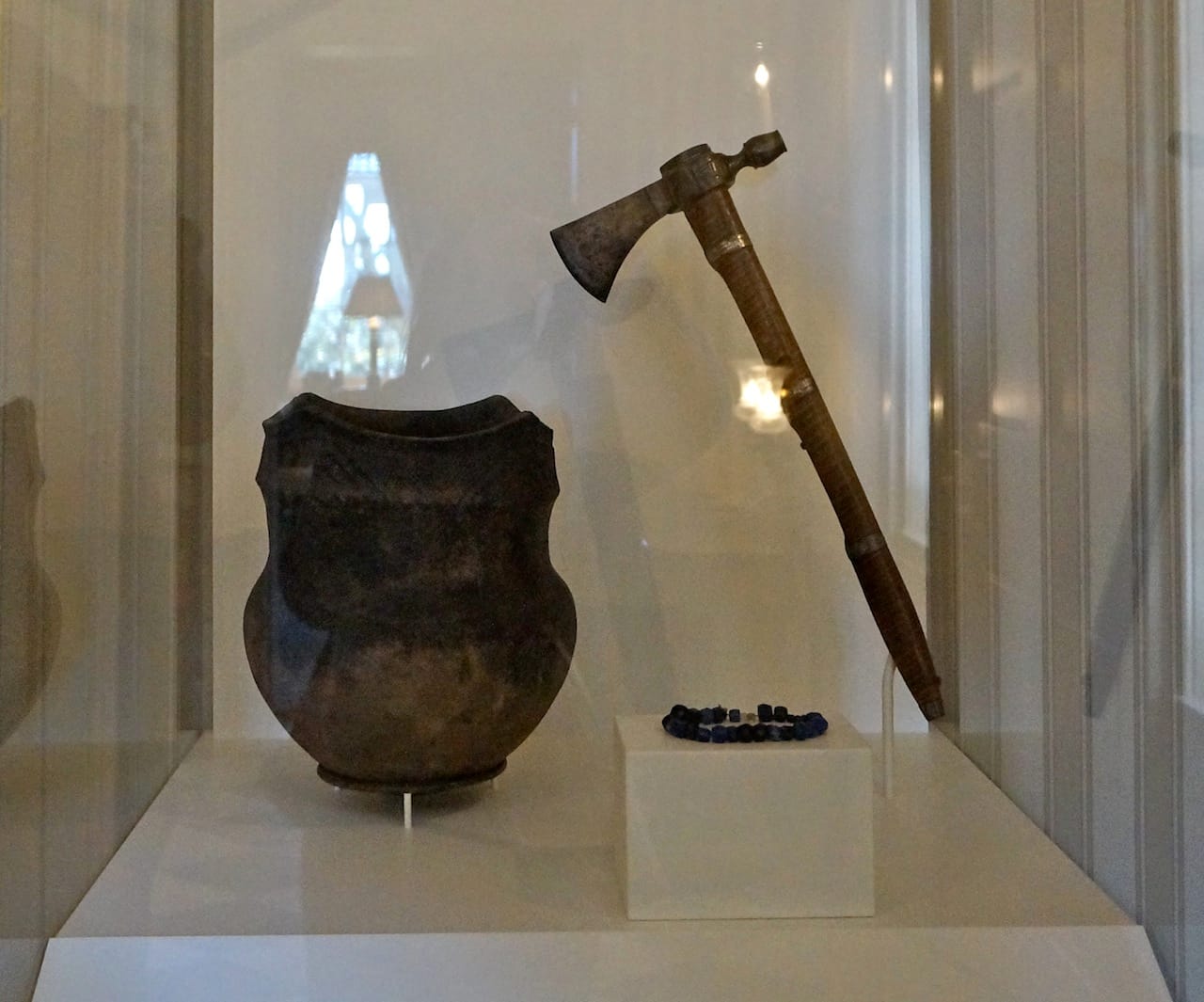

So, the New York State Gradual Emancipation Act, handwritten in slanted script, rests in a display case in a bright yellow room, alongside a postcard showing freed slave Peter Williams (ca. 1938) and a bill of sale for a slave. A painting across the room, a contemporaneous copy by artist Louisa Ann Colman of a work by Francis Guy, shows Downtown Brooklyn as it looked in 1820: snowy, sparse, and quaint. Just outside the door stands a display case holding three Native American artifacts, among them a pipe tomahawk given to the chief warrior of the Iroquois at the signing of the Treaty of Big Tree in 1797 — when the Seneca Nation was forced to give up nearly all of its remaining New York State lands to the federal government. Another room contains a facsimile of a different land treaty between Native Americans and colonizers, from 1683.

In a room across the hall, eight of Nicolino Calyo‘s watercolors from his set of 16 hang above a fireplace, colorfully depicting the Cries of New York — vendors selling everything from matches to bread on the streets of the 19th-century city. (A video made by students from Brooklyn College provides audio accompaniment, with actors calling out items like “pears!” in sometimes incomprehensible parlance.) They face a broadside titled “EXILES of ERIN!” (1809), which implores Irish readers to fight legal discrimination: “Will you bow yourselves down before these Tyrants? Or will you show them that you are men? That you are IRISHMEN?”

At Gracie Mansion, “EXILES of ERIN!” hangs above a stately striped couch, neat in a row with two other documents of the time. It loses a good bit of firepower in the process, as do many of the other newly displayed objects — decoration, after all, means adornment, and the grandeur of a well-manicured mayoral home is perhaps bound to subsume the small remainders of messy histories. But the rehang represents a strong gesture of inclusion from Mayor de Blasio and First Lady McCray, and even if its impact is limited, it remains an overdue and welcome one.

Windows on the City: Looking Out at Gracie’s New York is now on view at Gracie Mansion. Public tours of the house resume November 10; requests for tours can be made online.