Photojournalist Steve McCurry's Romanticized Visions of India

American Magnum photographer Steve McCurry, best known for his 1984 photograph of an Afghan refugee with piercing green eyes (Sharbat Gula), is one of the most celebrated photojournalists of our time.

American Magnum photographer Steve McCurry, best known for his 1984 photograph of an Afghan refugee with piercing green eyes (Sharbat Gula), is one of the most celebrated photojournalists of our time. His career started in 1978, after the work of Margaret Bourke-White and Henri Cartier-Bresson inspired him to take his first visit to India. This trip, on which McCurry used up 250 rolls of Kodachrome, would be the first of his more than 80 visits to the country.

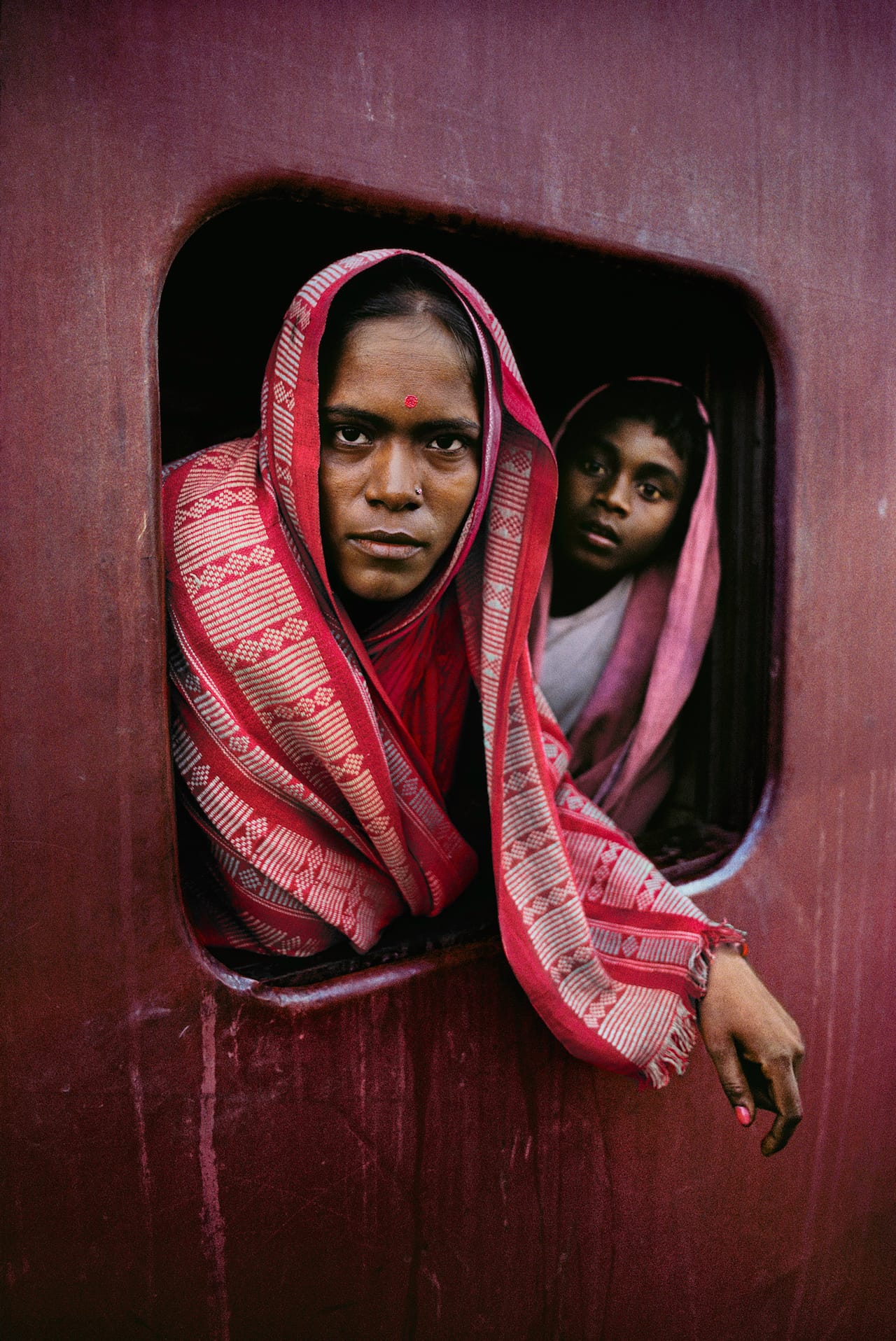

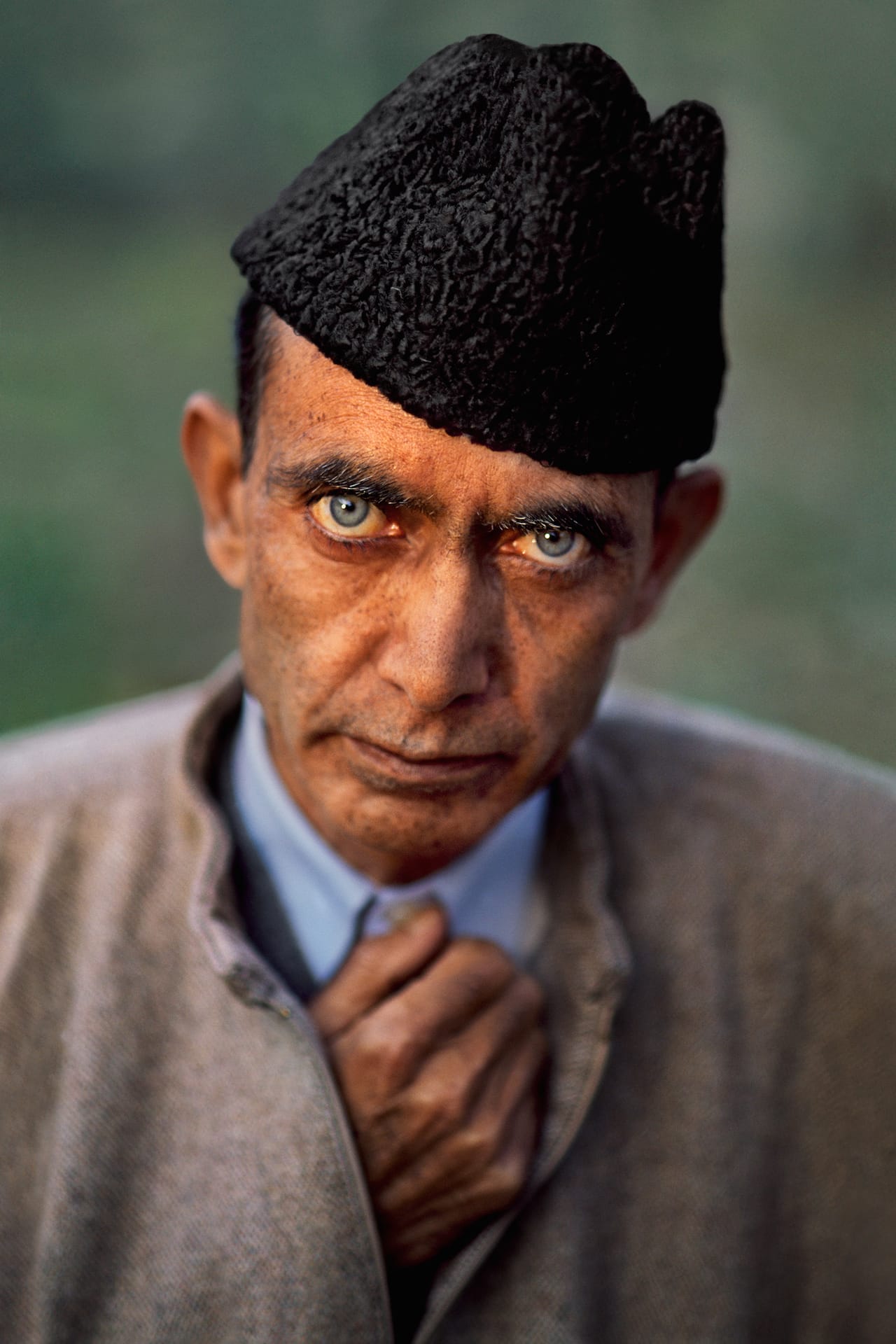

Steve McCurry: India, on view at the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art in partnership with the International Center of Photography, presents a selection of images from 30 years of the photojournalist’s travels across the South Asian subcontinent. They capture scenes from this land of 1.2 billion in brilliant, supersaturated colors: monsoon-flooded Bengali villages; Rajasthani desert dust storms; green-painted men crowd surfing at a Holi festival; Hindu pilgrims visiting shrines on the River Ganges; steam engines chugging past the Taj Mahal.

In terms of their composition, color, and specificity of subject — an old man carrying his rusted sewing machine through floodwaters, a young girl running past a hand-painted Bollywood movie poster — these are beautiful photographs.

The thing is, as a group, the photographs on view seem run through a particularly dreamy filter. McCurry usually isn’t one to shy away from conflict — he spent years covering the Iran-Iraq War, Lebanon Civil War, the Cambodian Civil War, the Islamic insurgency in the Philippines, the Gulf War, and the Afghan Civil War, and is known for his images of AIDS victims in Vietnam. But here, the curation presents a Western visitor’s romanticized vision of India as a magical land of color, light, holiness, enlightenment, collectivism, and carefree near-nakedness. While they reflect some vibrant aspects of the subcontinent, they don’t tell the whole story. The selected images edit out both the more banal, less “exotic” aspects of Indian life (there are no photos of, say, Indian office workers or McDonald’s servers here) as well as its less picturesque aspects (even images of monsoon destruction resemble stills from adventure films).

Presented without much context, the images on view gloss over the country’s fraught history of colonialism. If your only knowledge of India came from these photographs, you’d never guess an Englishman had ever set foot on its shores. They ignore the massive impact of globalization on the contemporary Indian economy, as well as many of its most pressing social issues. Instead, the show seems to cater to a fantasy-driven idea of India that appeals to Western spiritual tourists: the India of George Harrison and Ram Dass, the India of Eat, Pray, Love, the land of a thousand yoga retreats. While no single photography exhibit should be tasked with comprehensively summing up a place as vast and ancient as India, this one misses some pretty big things.

That’s not to say these photographs of awe-inspiring landscapes and holy men with saffron-colored beards won’t make you want to visit India. They probably will. Still, it’s worth questioning whether they reinforce Western stereotypes of the East instead of challenging them, and whether they only show you what you want to see.

Steve McCurry: India continues at the Rubin Museum of Art (150 W 17th St, Chelsea, Manhattan) through April 4.