Planting Frida Kahlo's Botanical Paradise in the Bronx

Plants and flowers appeared throughout Frida Kahlo's paintings, and although interpreting her art regularly evokes her biography of illness, injury, pain, and tumultuous love, the first exhibition to examine her work from a botanical perspective opens this week at a garden.

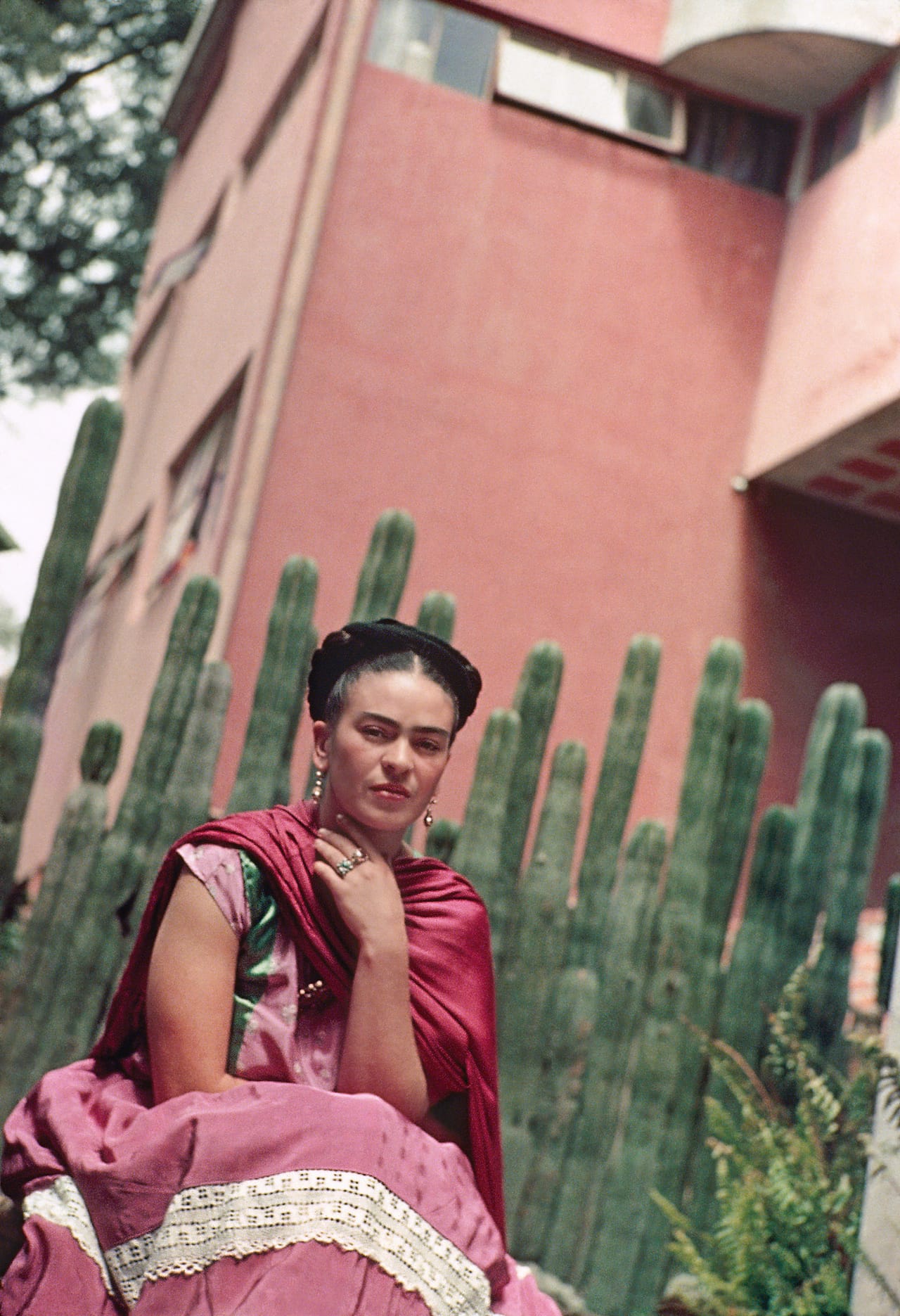

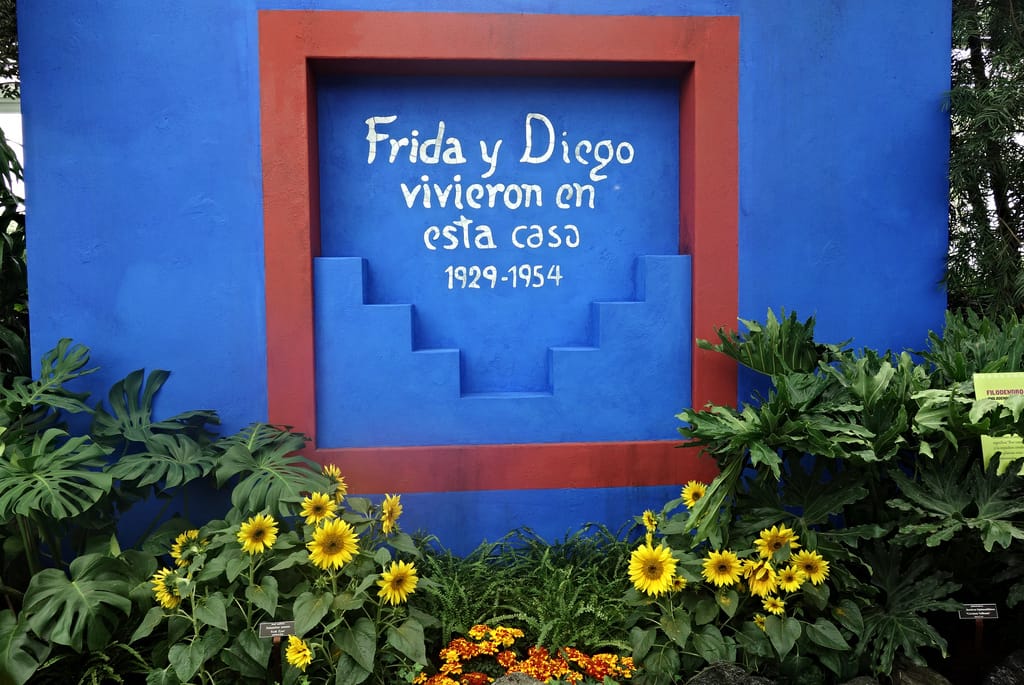

Plants and flowers appeared throughout Frida Kahlo’s paintings, and although interpreting her art regularly evokes her biography of illness, injury, pain, and tumultuous love, the first exhibition to examine her work from a botanical perspective opens this week at a garden. Constructing a tribute to the flora of her Casa Azul home in Coyoacán south of Mexico City, which she shared off and on with muralist Diego Rivera, the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) in the Bronx pairs this assembly of cacti, succulents, perennials, and other leafy specimens from her garden with a small exhibition of 14 drawings and paintings.

Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life opens this Saturday, revealing in the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory free-standing indigo-blue walls, terra-cotta pots filled with desert plantings, and a Central Mexico-inspired pyramid. The towering centerpiece is based on the one designed by Rivera after their remarriage in 1940 to display both Kahlo’s plant collection and their pre-Colonial artifacts. The NYBG Casa Azul garden evolved from extensive research on archive photographs, first-hand accounts, Kahlo’s art, and visits to the home itself which is now the Museo Frida Kahlo.

It’s not meant to be an exact replica, more an evocation of the feeling of stepping back in time, when from the 1930s to her death in 1954 the garden was a source of comfort and inspiration, especially as her health declined and she spent more time at home. In one corner of the conservatory, a studio space similar to Kahlo’s is set up with palette, pigments, and brushes beneath the shade of large-leafed plants. Curator Adriana Zavala and scenic designer Scott Pask have spent time with each detail, from the layered subtleties of the plant selections that go from desert to tropical, including plants native to Mexico and those she collected from abroad, to the careful matching of colors to Kahlo’s home.

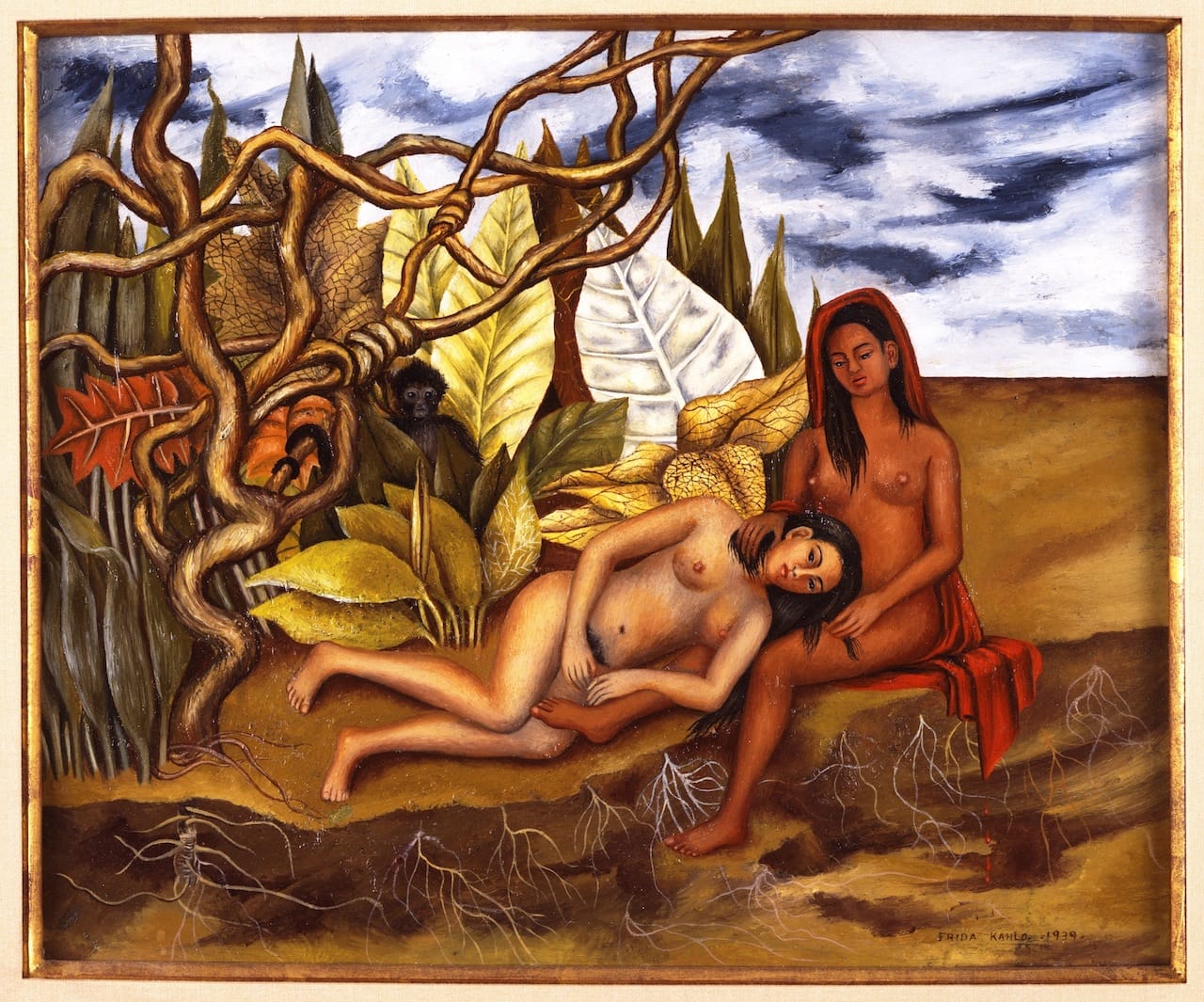

Elephant ears like those from her “Two Nudes in a Forest” (1939), on view in the NYBG library, thrive along the flat stone paths. Outside in the courtyard, an organ cacti fence borders the Victorian-style greenhouse windows in tribute to the one at the Casa Azul. In existing areas already growing at the NYBG, plants from Mexico are highlighted, such as the pink bougainvillea that she often wore in her hair. The exhibition demonstrates how all of the plants that appear in her art had specific meanings, such as connecting to her nationalism by representing Mexican horticulture, or emphasizing the cross-cultural history of the country through depicting more exotic plants.

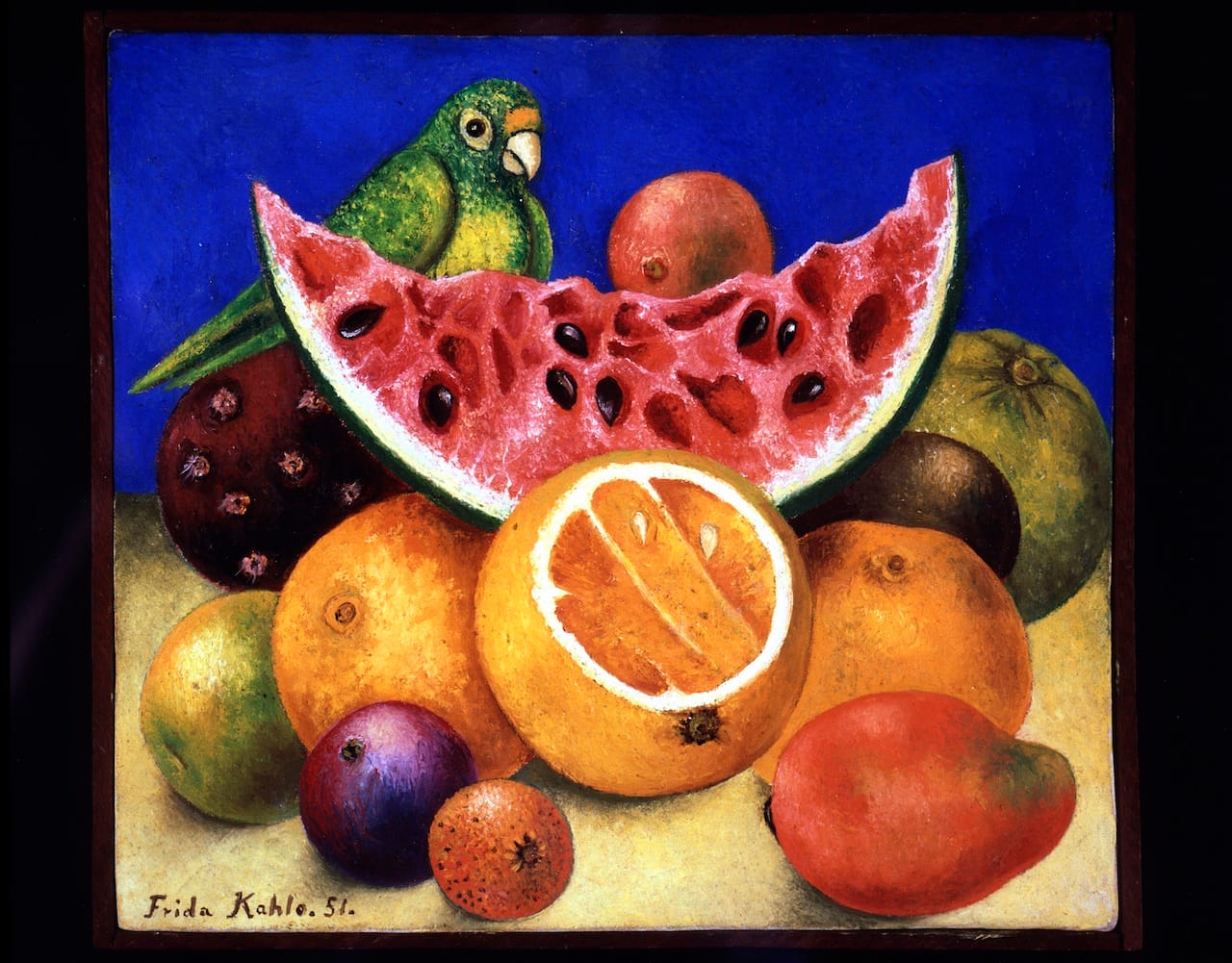

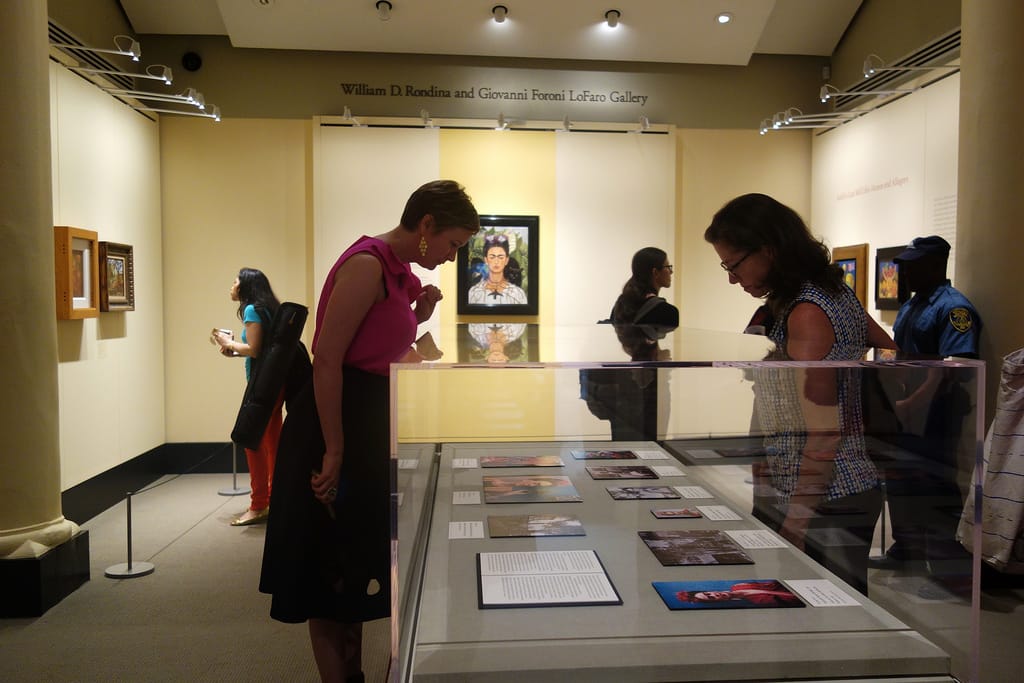

The exhibition of her art in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library’s Art Gallery, Kahlo’s first solo show in New York City in over a decade according to NYBG, is a small gathering of paintings and works on paper that demonstrate the symbolism and use of plants in her art. In the “Portrait of Luther Burbank” (1931), the famed botanist sprouts like a tree, with roots feeding on a corpse, illustrating how all flora and fauna is part of this cycle of life and death that nurtures new growth. Her beautiful “Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird” (1940) gazes from another wall, where a black cat and monkey creep from huge foliage and a zinnia and fuschia flower add a surreal touch as they turn into insects. A necklace of thorns adorned with a dead hummingbird draws blood from her neck, all suggesting the imminent consumption of her body by nature.

The NYBG has explored cultural figures through their gardens before, such as Emily Dickinson in 2010 and Claude Monet in 2012. As Karen Daubmann, director of exhibitions and seasonal displays, writes in the accompanying catalogue, they “wanted to delve into the story of the woman who has been examined through her pain and suffering and paint her in a different light.” Kahlo is arguably the most famous woman artist of the 20th century, and her images and stories still permeate our contemporary culture — last month, her love letters sold at auction and photographs of her wardrobe are currently on view in London. There seems to be no aspect of her history not dissected and put on public view, but the NYBG has highlighted an overlooked and essential element of her practice and person, and a way to explore it that respects how meaningful nature was to her life and art.

Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life opens at the New York Botanical Garden (2900 Southern Boulevard, The Bronx) on May 16 and continues through November 1.