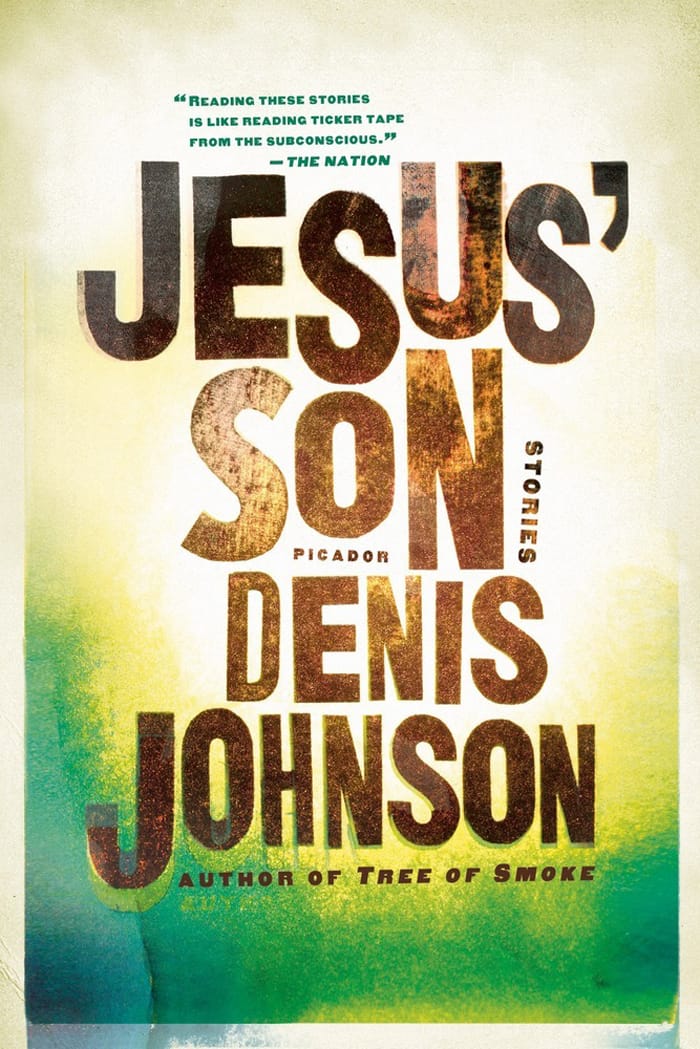

Reader’s Diary: Denis Johnson's ‘Jesus’ Son’

Reflected in sentences of throbbing beauty, the blind urge to self-destruction becomes a visionary quest

“I must approve the sentence that destroys me.” Somewhat incongruously, this line from Joseph Addison’s eighteenth-century smash Cato came to mind as I was reading, 24 years behind schedule, Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son. This is a fragmented modernist novel whose deliberately misleading subtitle, Stories, is just the first of its sly tricks: the parts are even more devoid of unity or conclusion than the whole. Addison’s enlightenment era’s vision of the moral sublimity of a man who willingly submits to the law in preference to the preservation of his own life inspired, among others, our own Founding Fathers. Two hundred years later — the book is set in the 1970s — Johnson’s drug-addled characters discover an equal but opposite sublimity in submission to the self-destructive dictates of anomie. As indifferent to other people’s lives as they are careless of their own, they aimlessly wander the blank American landscape wedded to bad luck and grasping after worse luck as if it were their last hope on earth. The novel could be speaking of itself when its narrator describes one of the various unspeakable dive bars to which he repairs, where “only the demons inhabiting us could be seen. Souls who had wronged each other were brought together here. The rapist met his victim, the jilted child discovered its mother. But nothing could be healed, the mirror was a knife dividing everything from itself, tears of false fellowship dripped on the bar.” Reflected in sentences of throbbing beauty, the blind urge to self-destruction becomes a visionary quest. Every car ride is a manifestation of the Freudian death drive, as the nameless protagonist shows on the very first page when he recalls how, picked up while hitch-hiking, “the traveling salesman had fed me pills that made the linings of my veins feel scraped out. My jaw ached. I knew every raindrop by its name. I sensed everything before it happened.” Knowing somehow that he is stepping into a car bound for an accident, “I didn’t care. They said they’d take me all the way.” Of course, as the use of the first person suggests, the narrator doesn’t quite go all the way — he has to survive to tell the tale. Still, I’ll admit to having been just slightly let down when, in the penultimate chapter or story or episode or whatever you want to call it, he outs himself as a writer-to-be, and still more so when in the last one, he finds Antabuse, a job at a rest home where part of his job is “to touch people,” and a glimmer of potential redemption. The thing is that when Johnson depicts the unredeemed, I realize I know them, though I wish I didn’t, and I begin to wonder if their vacancy is a reality I’ve merely succeeded in repressing. But I approve the sentences that destroy them.

Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son: Stories (1992) is published by Picador and is available from Amazon and other online booksellers.