Saving a 220-Year-Old Eagle, the Oldest Military Sculpture in the US

One of the oldest locally-carved sculptures in New York City has weathered two centuries out on Governors Island in the New York Harbor.

One of the oldest locally-carved sculptures in New York City has weathered two centuries out on Governors Island in the New York Harbor. The sandstone eagle up on the monumental arch to Fort Jay dates to the 1790s, and is currently the focus of a conservation project to protect its surviving pieces and replace components that were lost to Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

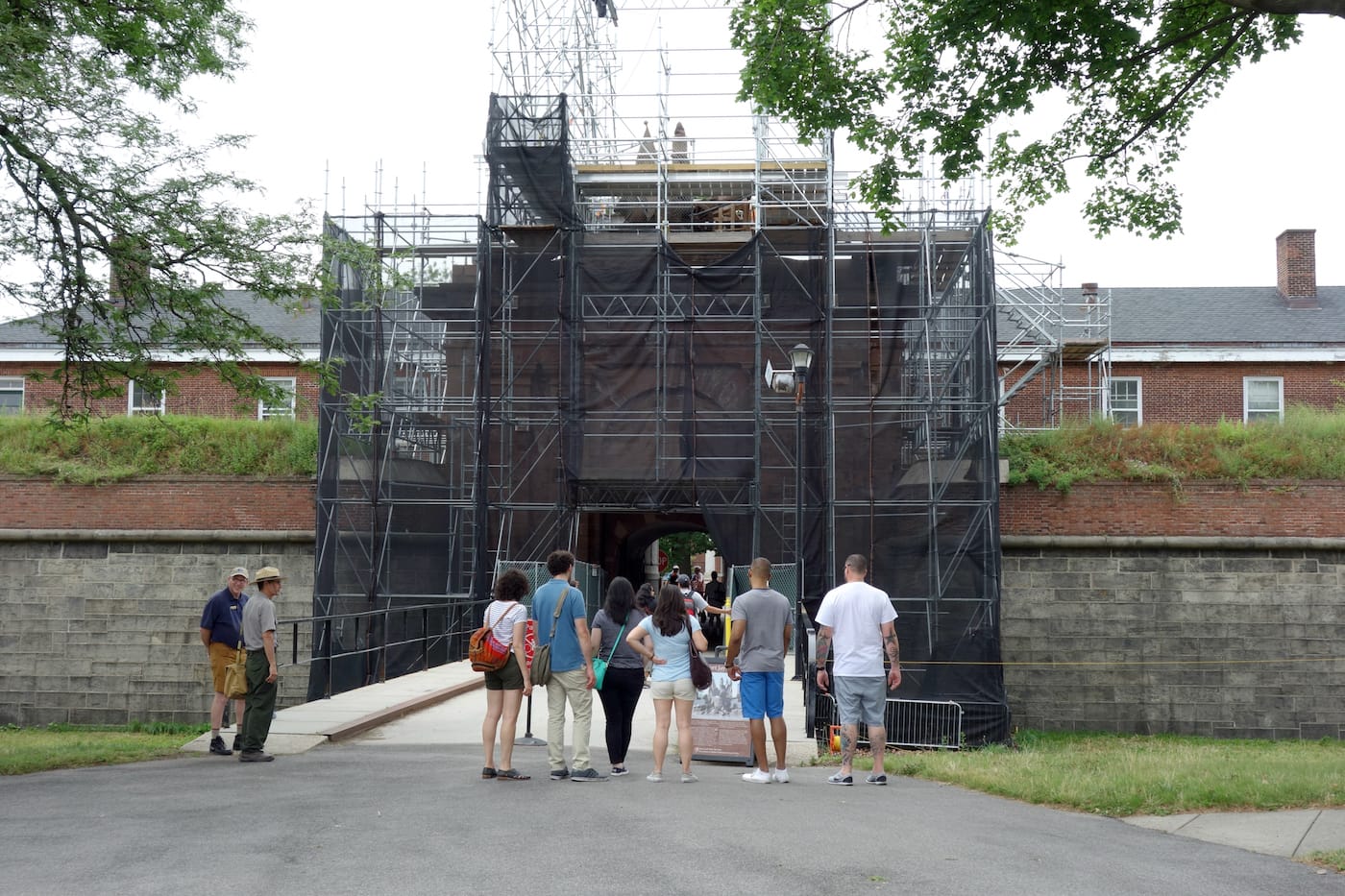

Rangers with the National Park Service, which manages the site, along with conservation specialists recently hosted free scaffold climbs for the public to “meet the eagle” on its historic perch. While the former military base has been open to the public since 2003, the 15-foot eagle and its surrounding tableau of carvings have often been overlooked in the greater expanse of buildings and green space on the island. This is actually true throughout its history, which remains fuzzy and vaguely documented. The National Park Service began its study of the Trophée d’Armes sculpture composition in 2005, and carving is now underway on-site to restore parts of the deteriorated sculpture as part of a #SaveOurEagle campaign.

The arch itself is remarkable, designed by architect Joseph-François Mangin who also worked on the 1828 City Hall. However, little is known about the 18th-century sculptor behind the eagle, which is posed grasping a shield adorned with the rising sun, and flanked by flags, cannons, and other military pomp. Kevin C. Fitzpatrick in his Governors Island Explorer’s Guide writes that the “first illustration [of the eagle] is from around 1861,” and there’s some lore that the sculptor was a prisoner on the island. The New York Times reported that in government records an artist called “Le beau” is credited for designing the tableau, although the sculptor (or sculptors) who executed it remain unknown. And it’s unclear if the piece was ever whole. Matthew Brady’s 1864 photograph, the earliest known photographic image of the work, shows the eagle without wings.

National Geographic calls the bird “the earliest domestically carved military sculpture in the nation.” There are older imported statues, and older carvings — the grave of Richard Churcher from 1681 in Manhattan’s Trinity Churchyard is often cited as New York City’s oldest — but it represents a significant moment in American monuments.

Craig Oleszewski, senior exhibit specialist, led the scaffold climb with Ranger Lindsay Davenport (not the tennis star), and pointed out that some of the work was likely carved at the elevated height, while other pieces were joined later. Down below, he’s working with his conservation team using some sandstone from England that’s often used in restorations, and other sandstone salvaged from a Connecticut bridge by the Smithsonian Institution. In 1903, the US Army conducted its own restoration on the eagle, so stucco mixes with the sandstone, and alterations in 1965 further changed the sculpture. However, Hurricane Sandy was the most dramatic moment, when the gusting wind toppled two of the flags and they shattered on the guard house below.

The goal of the current restoration is to return the eagle to its pre-Sandy state, a condition which was luckily 3D mapped in 2006. Recently, the sculpture was part of the Vote Your Park competition organized by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, but it lost out to projects at more prominent National Parks like Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon. Yet the work continues on protecting the eagle, and seeing to its survival into the future. Looking over to the Manhattan skyline from the scaffold, it’s remarkable to think that this sculpture was here long before any of those skyscrapers, and it has witnessed so much of the city’s history.