Review of Street Art New York, by Rojo and Harrington

Imagine a gallerist bringing new art works into the gallery. She pulls her truck up to the gallery curbside, gets out, and starts taking some paintings out of the truck bed. She takes one out just as she realizes that she hasn’t unlocked the gallery doors. So, she places the artwork on the curb and

Imagine a gallerist bringing new art works into the gallery. She pulls her truck up to the gallery curbside, gets out, and starts taking some paintings out of the truck bed. She takes one out just as she realizes that she hasn’t unlocked the gallery doors. So, she places the artwork on the curb and sets off to unlock the gallery. This person has intentionally placed art in the street. Is it street art? Obviously not. So what makes something street art if not the art’s being intentionally placed in the street? It might even seem that street art needn’t be literally in the street at all, so long as one accepts that Blu’s MUTO and similar works are street art — as a digital video it has no literal or direct connection to the street. Street artistic status must hinge on something else. So what is it?

The most promising proposal I have been able to think of is this: street art is art whose use of the street is essential to its meaning. That is to say, street art is art that uses the street, either as an artistic material or as an artistic context (or both), in such a way that any acceptable interpretation of it must refer to the way in which that use of the street gives the piece its significance. (This implies that graffiti and street art are quite different arts.) If this is right, then for an artwork to be street art it must use the street. That means that no art in a traditional gallery or art space is street art. It might have been made by a “street artist” but so what? Street artists can also make hot dogs and folk songs. It might even look a lot like the stuff we see on the streets — but it’s not street art. It is gallery art masquerading as street art. This illusion has duped many an art-buyer into paying lots of money for “street art,” but really they were just buying (often terrible) gallery art. Its being terrible gallery art does not imply that it was bad street art. In fact, it was probably very good street art — that’s why the artist was invited to make the same thing for a gallery show.

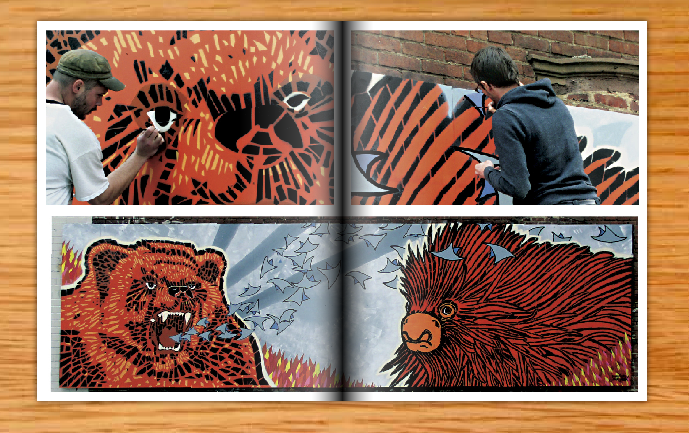

It follows from this that to capture street art in all of its glory — either as a critic or as a documentarian or photographer — one must capture the special way that the artwork uses the street to give it the meaning it has. One must capture its specific street context, illustrate the way that it was meant to strike or interact with passer-bys, or show how its import depends on the specific community or neighborhood in which it was placed or created. There is one especially good way to ensure failure at this: pretend that the street artwork could perform the same function in a gallery, that is, pretend that there is no difference between gallery art and street art — that street art is merely art-in-the-street that does not really depend on the street in any deep way. This will force the critic or documentarian to totally ignore the work’s specific relation to the street, and it will pressure the street art photographer to suppose that the picture frame should stand in for the absent gallery art frame

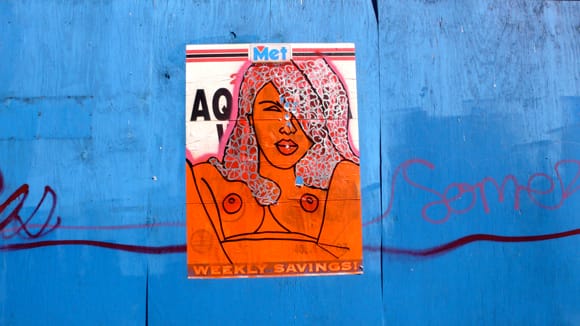

The majority of photographs in Street Art New York — a new book of street art images by Jaime Rojo and Steven P. Harrington, the overseers of the influential and very active street art website Brooklyn Street Art — exemplify this failing. The photographic persona in these images is a latent gallerist. The picture frame acts like a gallery frame. Their extremely tight framing eliminates nearly all artistic context — in some cases there is no clear sign that the piece is even on the street (see page 58). The images are utterly disembodied and dislocated.

On nearly every page, we are given no information — visual or linguistic — about the date, location (other than “New York City”), context, or artist intention. We don’t know whether the work we are seeing is part of a series (an important concept in street art) or whether the artist has done other similar works. The images are in no particular order (other than starting with a smattering of works by REVS, which seems appropriate), and although images are often juxtaposed for some vague reason, we are never given any explanation why. Indeed, the juxtaposition leads us to believe that the works have something in common when they could very well be totally different. Is it supposed to be obvious? The book seems to presuppose that the answer is “Yes,” or at least that it doesn’t matter. This is shown not only by the lack of information about the artworks, but also by putting images of truly awful art in the same collection with images of clearly amazing work. Compare, for example, pages 92, 124, and 144-45 with the work by Judith Supine, Dain, and C215. There is also a disappointing lack of the best work from some of the more talented artists working during the time that these photographs were taken (which is mostly, it seems to me, from 2007 through 2009). Aakash Nihalani and Dan Witz, for example, produced several very striking works, yet only some of the weakest are shown in this book (see pages 79-81).

The view that critical attention to, and critically relevant information about, street art doesn’t matter is symptomatic of what seems to be a general trend among street art enthusiasts. There is a general disdain, it seems, for thinking about street art — street art enthusiasts tend to resist thinking about artistic value, artistic influence, artistic context, or pretty much anything related to art history and criticism. Oddly, this is clearest on the most popular and dedicated street art websites, like Brooklyn Street Art, Wooster Collective, and Flickr street art pages. Wooster Collective seems dedicated to not disclosing why they like what they like and suppressing their (negative) critical thoughts. But don’t be fooled: Wooster Collective is a highly curated collection of images selected from a vast bay of possibilities sent directly to the site with the hope of being, one day, featured there.

The closest these sites seem to come to art criticism is the occasional, and sometimes helpful, artist interview. Via their website Brooklyn Street Art, Rojo and Harrington have been especially good at this, posting informative interviews with street artist about their intentions, processes, and the meaning of their imagery. It is a shame that Rojo and Harrington did not incorporate into their book what must be a fascinating body of knowledge about street art and street artists. It seems to me that this is exactly the opportunity that the book form offers. But as it is, the book offers little that we couldn’t have easily found online, and often in better quality (several of the images in this book appear to be poorly magnified digital photographs).

The book is clearly the result of an intense dedication to and love for street art. Rojo and Harrington have done a lot to support contemporary street art practice and appreciation. But as I argued in my review of Banksy’s Exit Through the Gift Shop, such dedication can cause one to overlook the current needs of street art. Street art does not need more uncritical enthusiasts, weak “gallery shows,” naïve art-buyers, and amateur practitioners. It is time for a new phase in street art — one that takes the practice and its practitioners more seriously and subjects it to the kind of attention it deserves. But watch out, it might be critical.

Street Art New York By Steven P. Harrington and Jaime Rojo, Foreword by Carolina A. Miranda (176 pages with 200 color illustrations, Hardcover)