The Decadent Dakota: New York's Luxury Apartment Pioneer

There's no shortage of myths and legends about the Dakota, that formidable, castle-like apartment building at West 72nd Street and Central Park West in Manhattan.

There’s no shortage of myths and legends about the Dakota, that formidable, castle-like apartment building at West 72nd Street and Central Park West in Manhattan. There’s the unshakeable attachment to the 1980 murder of John Lennon just outside, and Yoko Ono’s continued residency. There’s its turn as the exterior of the eerie home of Mia Farrow and her tormenting satanists in Roman Polanski’s 1968 Rosemary’s Baby. And like any old structure, it has its share of ghost stories, including, as related on a recent Bowery Boys podcast, the specter of its developer Edward Clark.

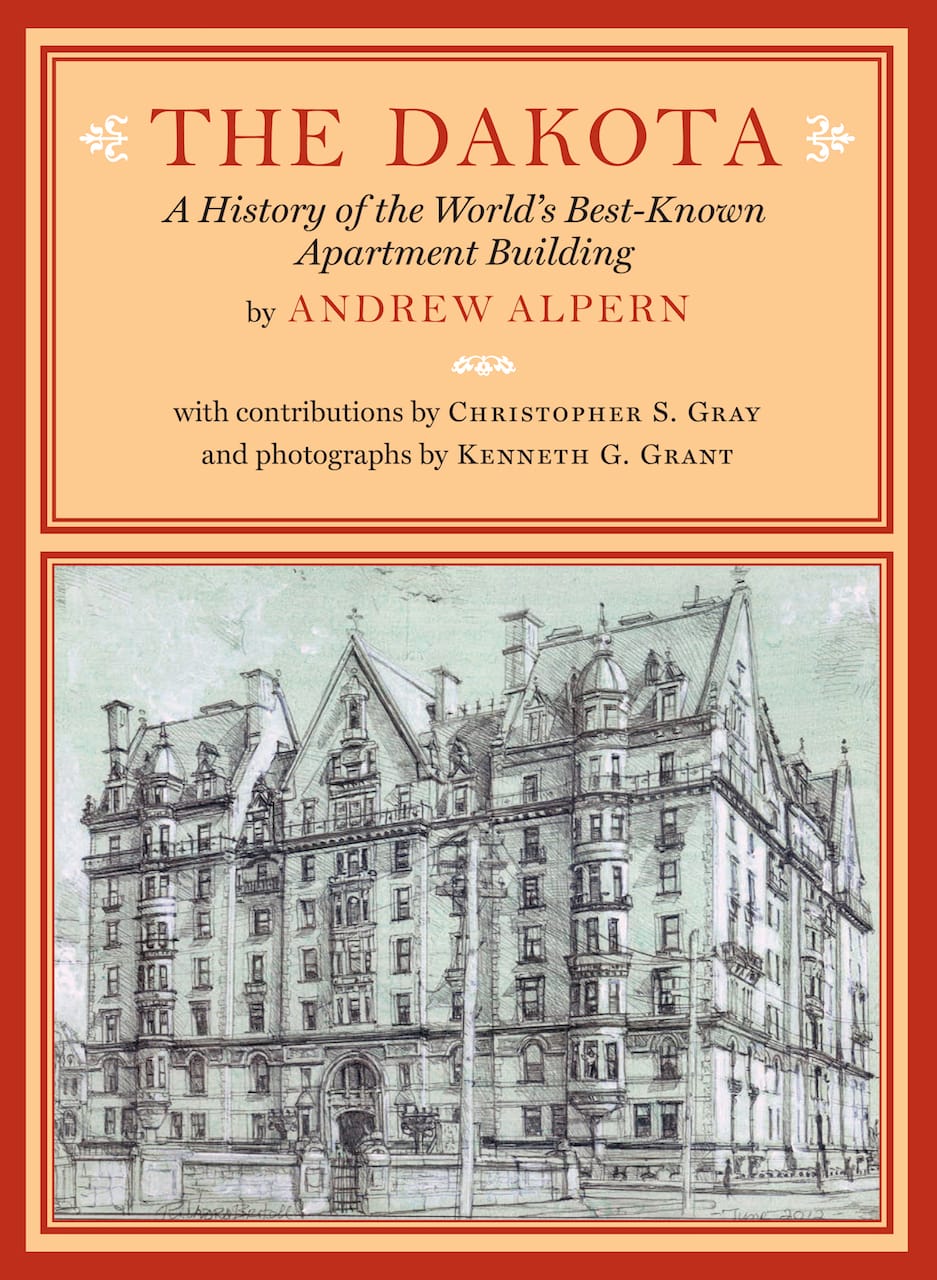

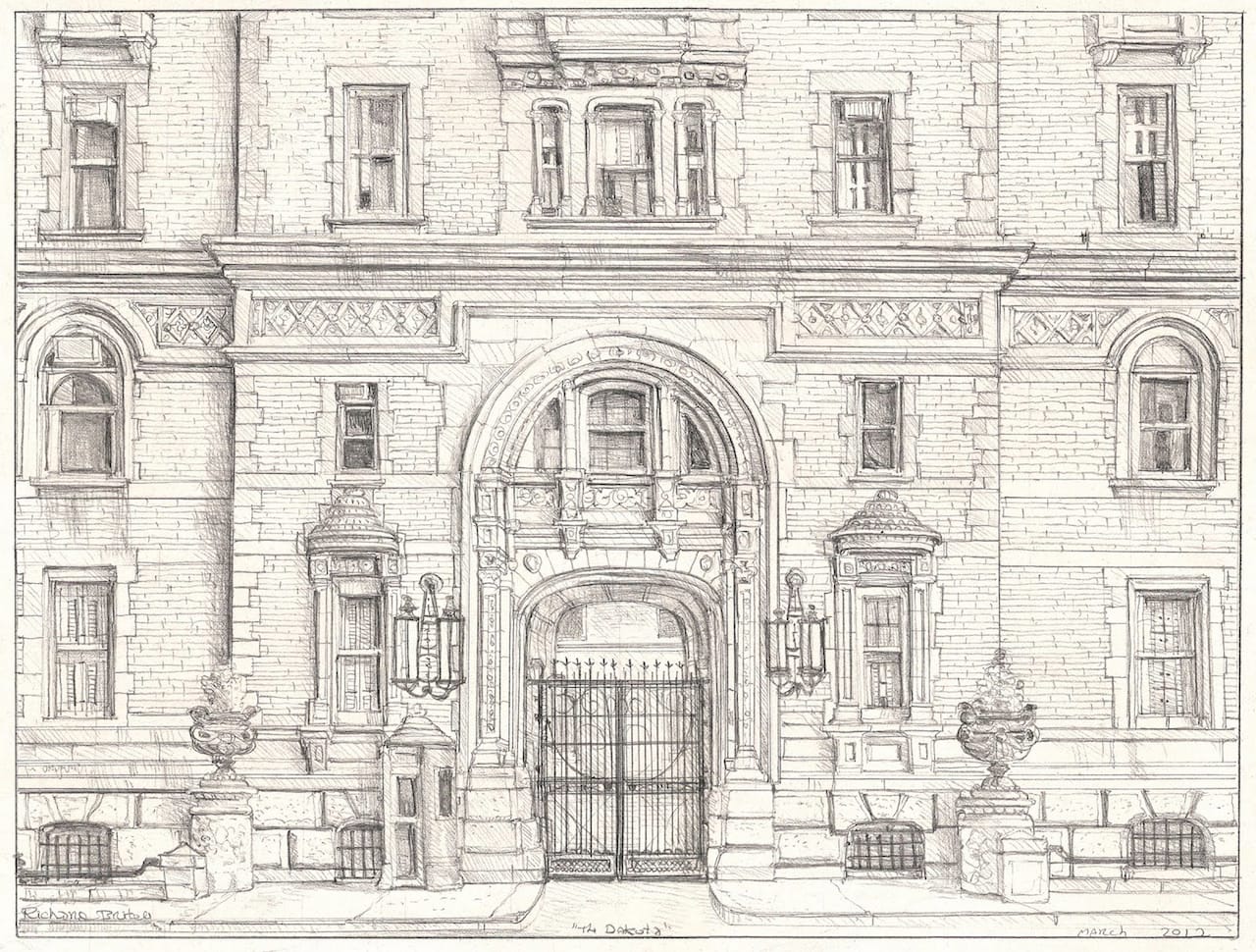

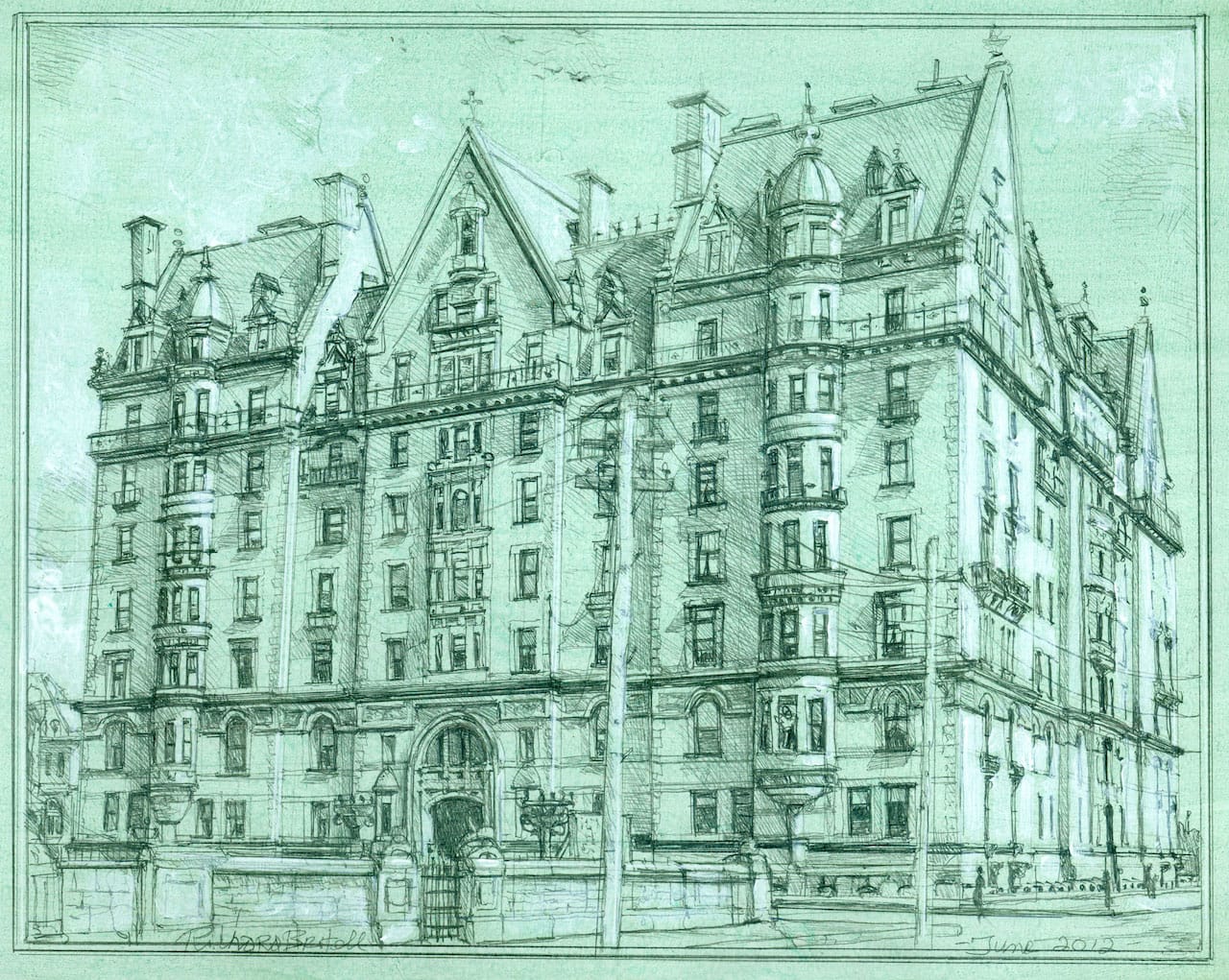

You won’t find any of that in the new book The Dakota: A History of the World’s Best-Known Apartment Building by Andrew Alpern, out last month from Princeton Architectural Press. Instead, the architectural historian is interested in the Dakota’s 19th-century beginnings, and how the completion of the building in 1884 by Clark influenced apartment-style living in New York City and beyond. Clark was a co-founder of the Singer Sewing Company, and with architect Henry Hardenbergh, whose designs were also behind the Plaza and the now-demolished Waldorf and Astoria hotels, envisioned a goliath structure with peaking roofs, and even a dry moat bordered with iron dragons. “Clark’s project was the pioneer, and unquestionably the first truly luxury apartment building in New York,” Alpern writes.

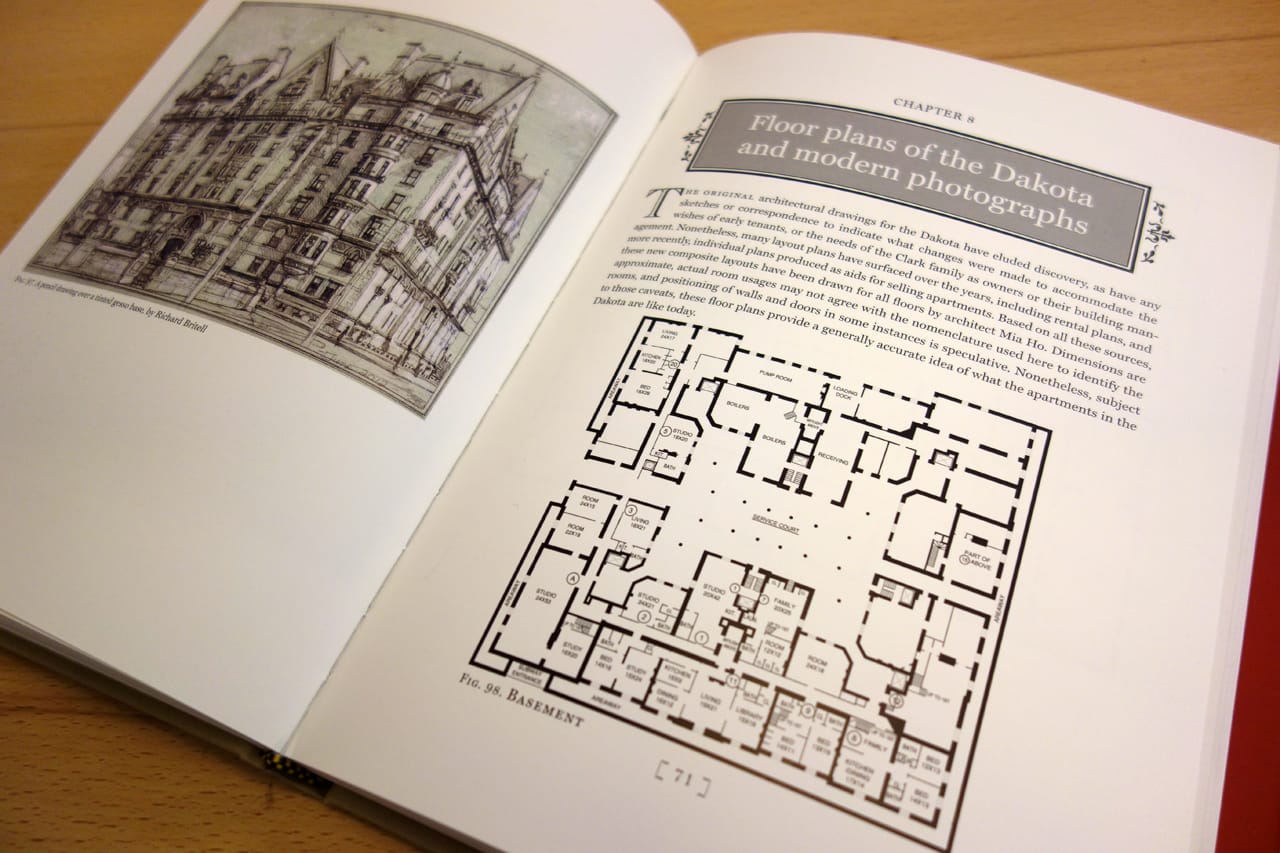

For The Dakota, Alpern sourced descriptions from the writing of architectural historian Christopher Gray, who shared his articles for mining, and collaborated with architect Mia Ho on recreating floor plans from rental plans, alteration drawings, and other sources because “the original architectural drawings for the Dakota have eluded discovery.” Interestingly, the plan for the Dakota wasn’t to be an astronomically priced palace, as it is today, but something for the upper-middle class.

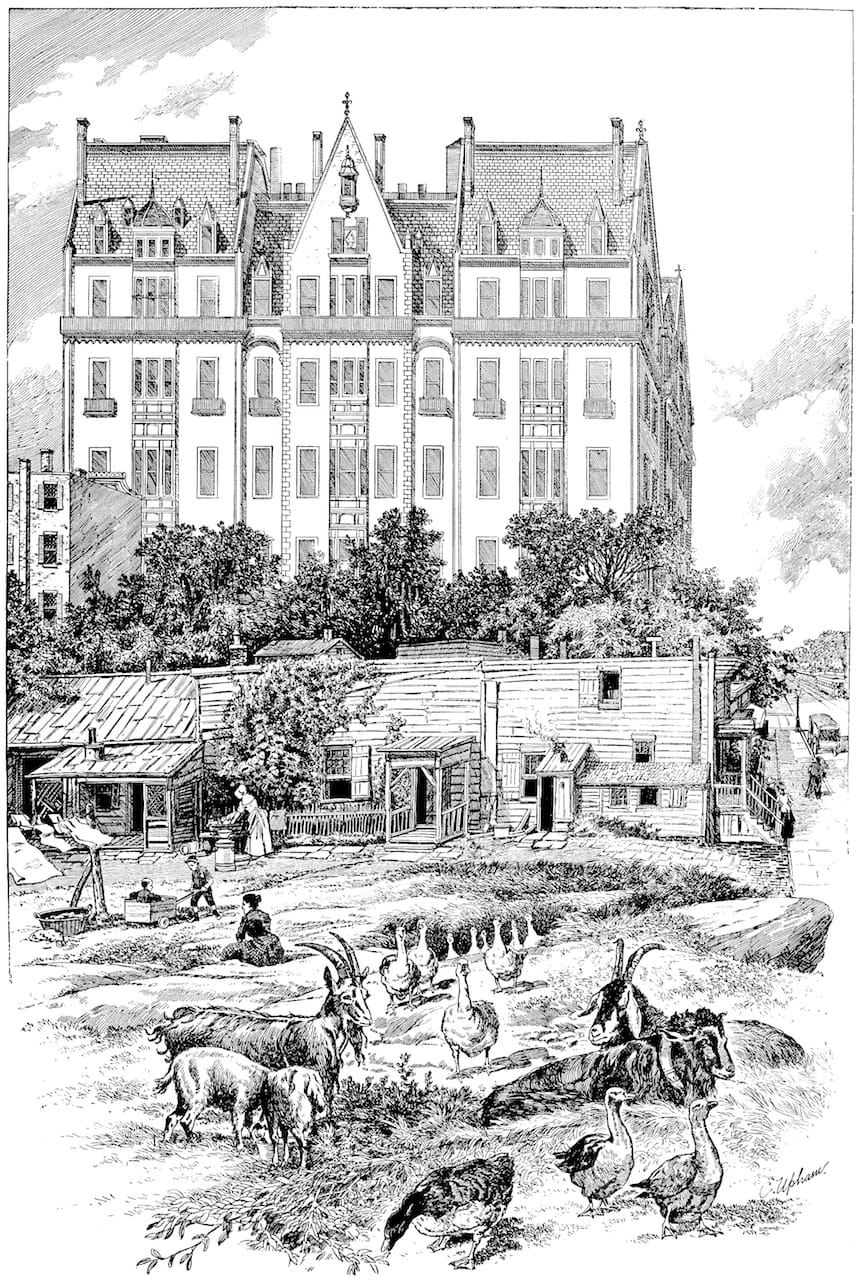

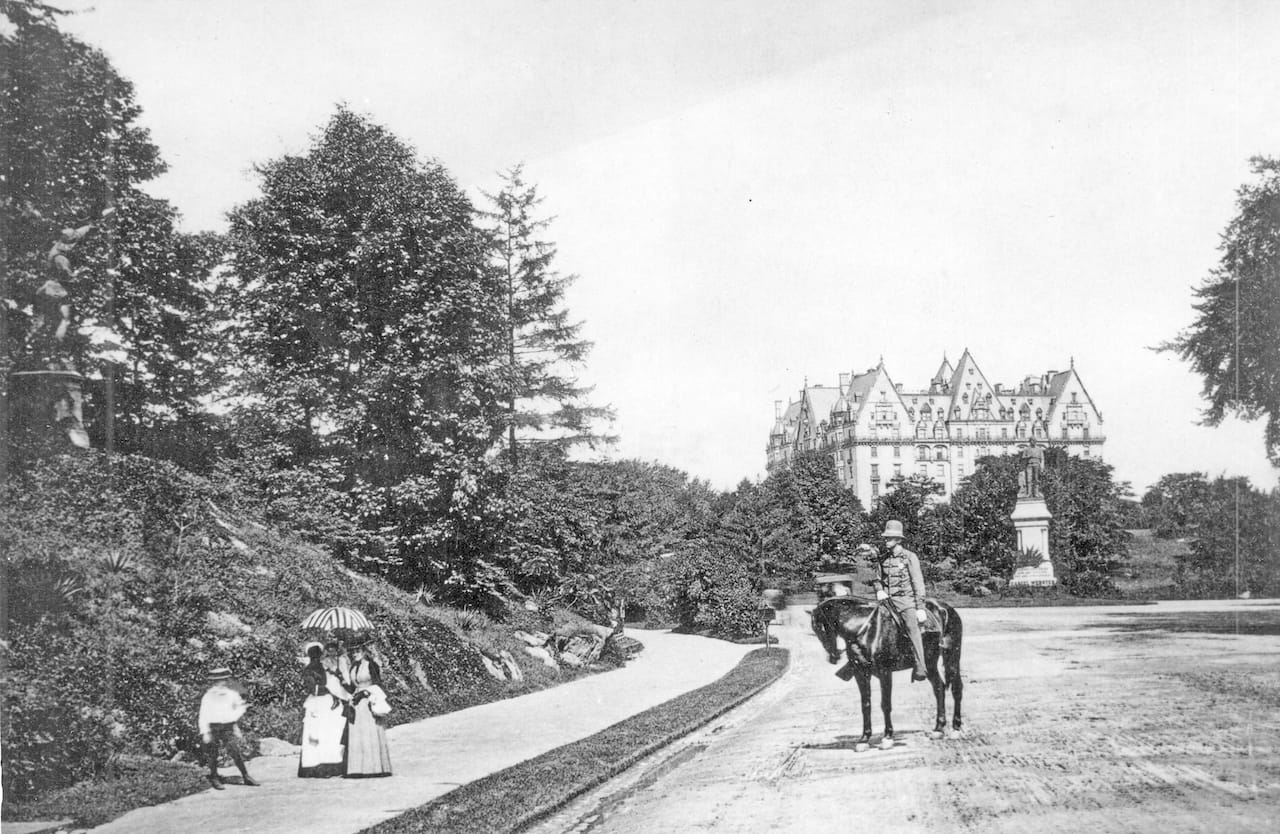

Contrary to popular belief, the Dakota didn’t get its name for being so far from Manhattan civilization that it might as well be the Upper Midwest. Alpern writes that “while it is true that when the Dakota was built there was little in its immediate area, that ‘little’ included the American Museum of Natural History, the fast elevated trains running up what is now Columbus Avenue, and several score of row houses.” He adds that “everyone agreed on the great prospects for the area: The El made commuting downtown from the West Side faster than by surface transit from much father south, and Central Park had been a major tourist attraction for a decade … West Side terra was hardly incognita, or even Dakota.”

Still, the Renaissance-inspired building was a contrast to the low constructions around it, which felt rural in many ways. A whimsical drawing from an 1889 issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper shows country homes with goats and ducks running free, and the startling silhouette of the Dakota looming behind. The area had been gridded since the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, waiting for the population to push north. With its 60+ apartments, some with up to 20 rooms, all with high ceilings, fine wood walls, and staircases built from marble, it aimed for a new kind of communal living for a city where the wealthier classes were interested in opulent convenience.

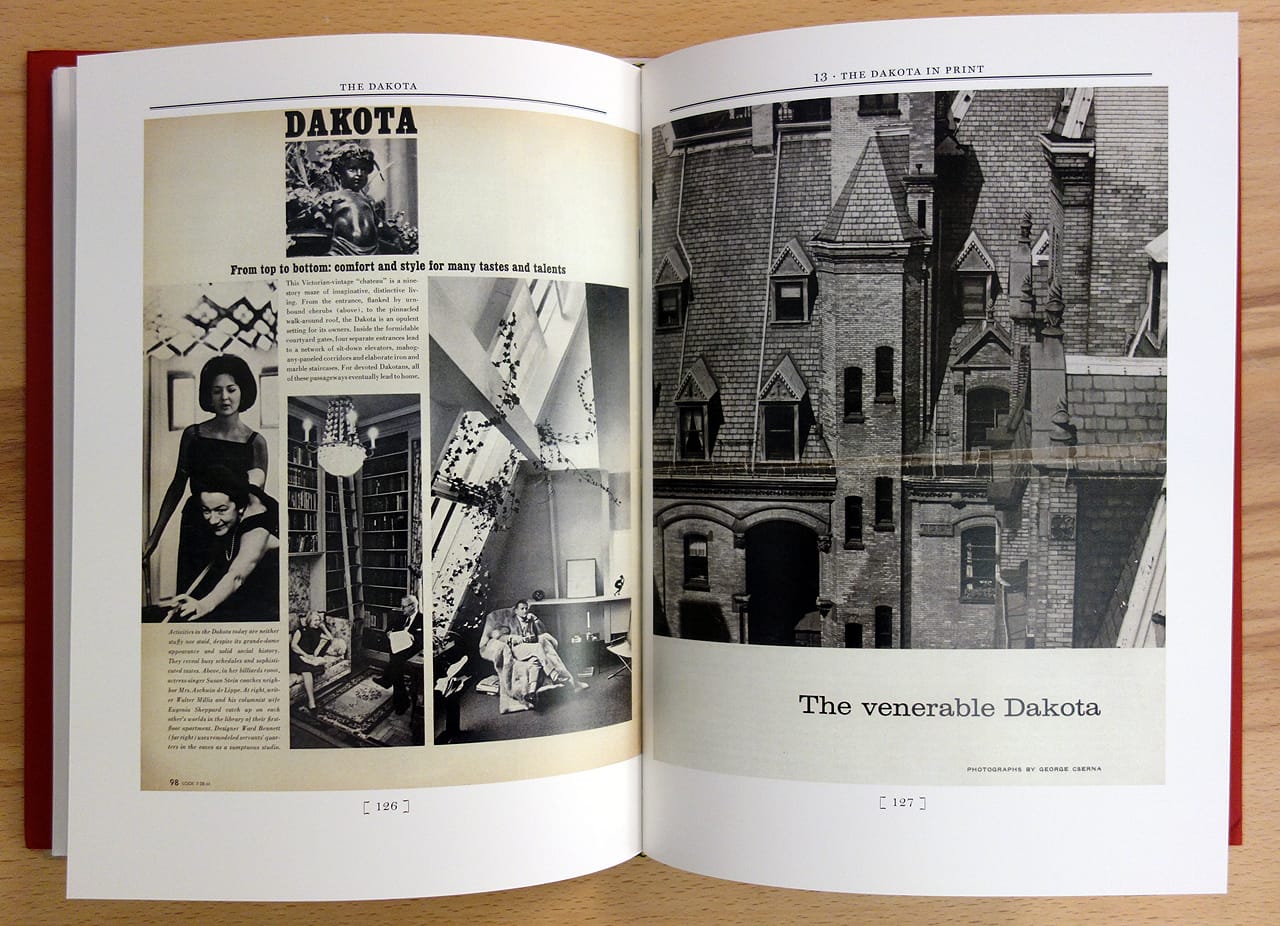

Along with other buildings going up at the same time like the Osborne, Navarro, and the Gramercy, the Dakota was pivotal in introducing New York City to the idea of living in apartments as desirable, even elitist. Long before famous names like Judy Garland, Rudolf Nureyev, Lauren Bacall, Leonard Bernstein, Boris Karloff, and numerous others made it an iconic status symbol, it was a reflection of the city’s growth and emerging 20th-century character.

The Dakota: A History of the World’s Best-Known Apartment Building by Andrew Alpern is out now from Princeton Architectural Press.