The Delicate and Daring Works of a Forgotten 17th-Century Japanese Painter

WASHINGTON, DC — Over the course of his career in the 17th century, the Japanese painter Tawaraya Sōtatsu produced a large body of intricate and decorative works on paper.

![(Artist) Tawaraya Sotatsu; Japan; 17th century; Ink, color, gold, and silver on paper; H x W (overall [each]): 166 x 369.9 cm (65 3/8 x 145 5/8 in); Gift of Charles Lang Freer](https://hyperallergic.com/content/images/hyperallergic-newspack-s3-amazonaws-com/uploads/2015/12/1-f1906-231-r.jpg)

WASHINGTON, DC — Over the course of his career in the 17th century, the Japanese painter Tawaraya Sōtatsu produced a large body of intricate and decorative works on paper. While he owned a frequented and respected studio in Kyoto known as the Tawaraya, he nonetheless faded into obscurity when he passed away in the mid-1600s — until the early 20th century, when art historians began exploring his work, leading to a revived interest. Sōtatsu: Making Waves, an exhibition at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, explores and celebrates his dynamic art; it’s the first exhibition outside of Japan devoted to one of the country’s masters of traditional ink works on paper.

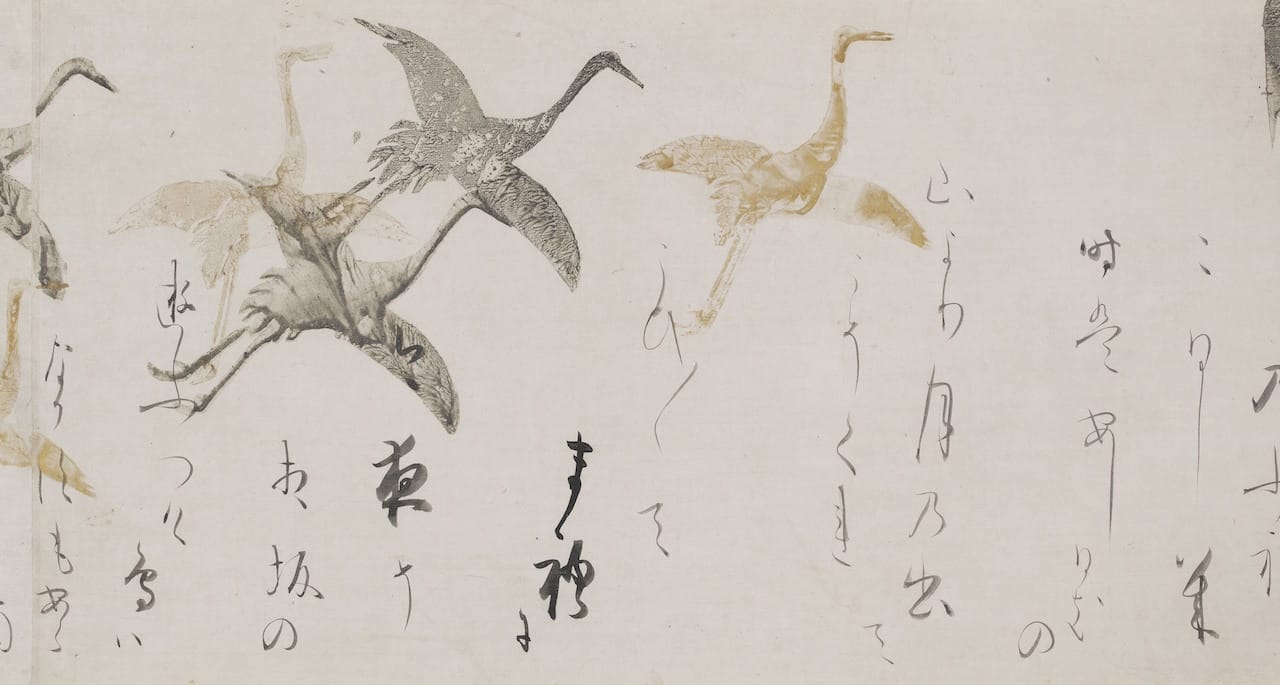

Sōtatsu is recognized as a forerunner of the Rinpa school; his particular ink-painting technique exudes the vibrancy characteristic of the movement, evoking the energy of the nature scenes he often depicted. This applies across the impressively wide range of formats in which he worked, from handheld fans to sprawling, multipaneled standing screens. The exhibition presents a number of the latter, the most famous being “Waves at Matsushima” (early 1600s). Comprised of a pair of six-panel screens, the painting features glistening waves crashing into multicolored rocks, all set against a golden background.

The screens, which greet viewers at the entrance to the show, are an astounding introduction to Sōtatsu’s work: their surfaces appear to undulate in all directions due to the watery whirls and curves of the mountains, with the paint catching light to shimmer as one moves past the panels. More than simply an accoutrement for the monastery for which it was created, “Waves at Matsushima” was an aesthetic object that was displayed on certain public occasions.

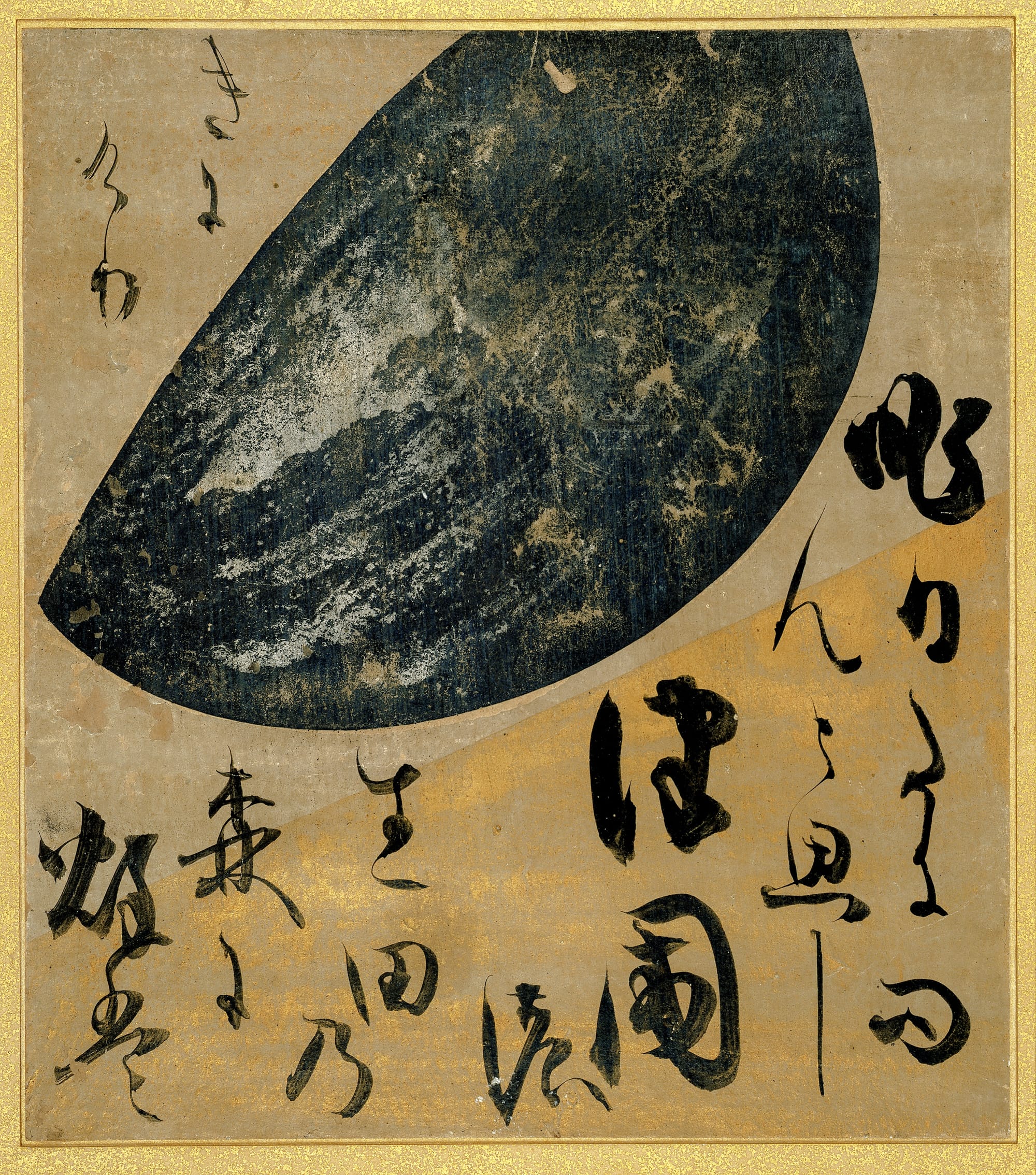

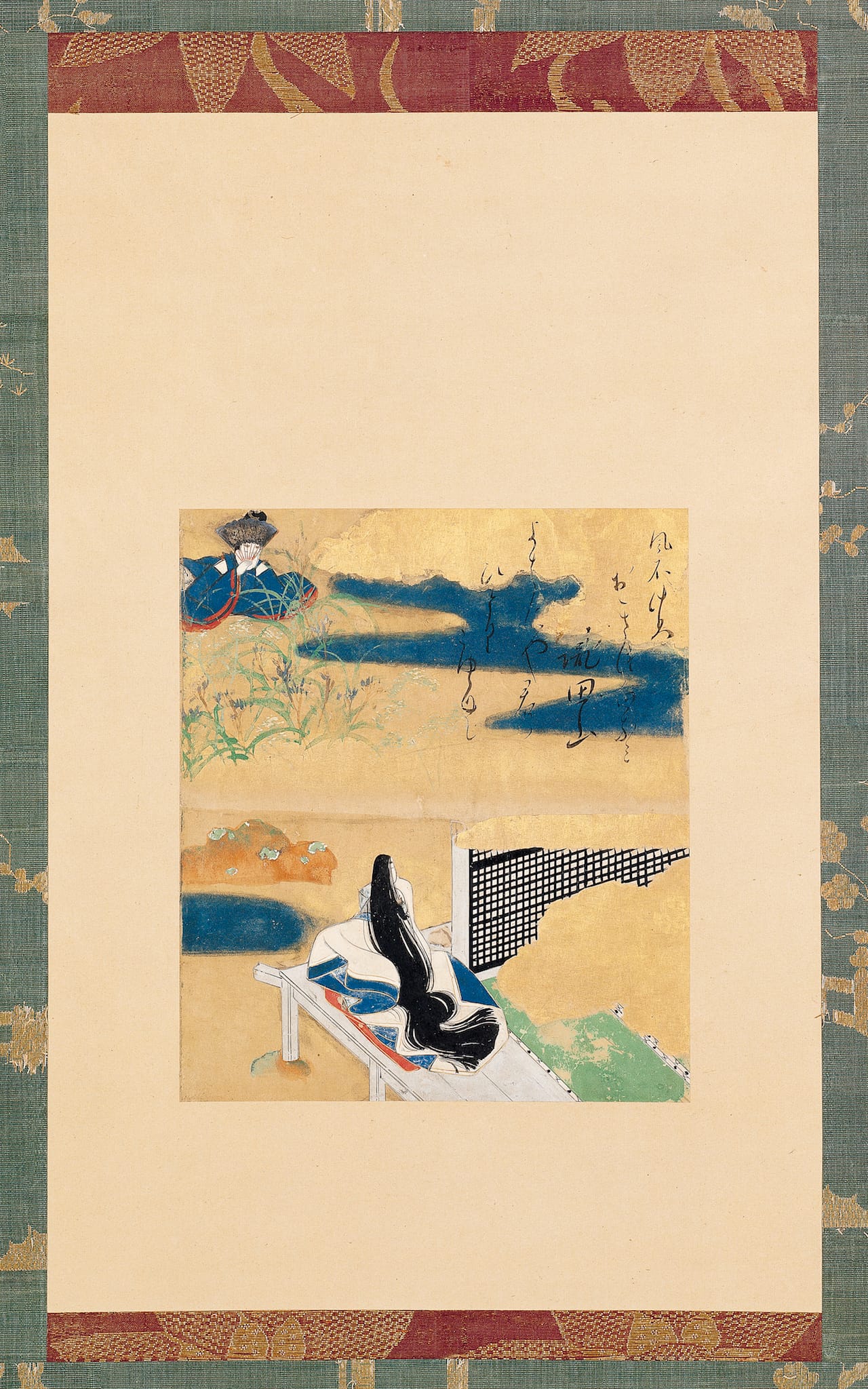

Sōtatsu’s devotion to embellishing the functional is even more remarkable in other screens to which he added objects. One pair features 36 staggered poetry cards, floating in a golden scene that elegantly integrates views of a room and its surrounding nature; the texts touch upon themes of love, travel, and the seasons. Another pair consists of eight-panel screens onto which he mounted a total of 48 hand-painted fans, featuring scenes from traditional narratives such as Tales of Ise and the Tale of Genji. Painstakingly painted after Sotatsu had pasted them on the gold foil–flecked screen, the fans’ multifold surfaces presented an especially unique challenge for executing his design. Sōtatsu also produced individual handheld fans embellished with text that allowed people to carry quotations and images of then-popular stories with them — portable bits of Japanese culture.

Many of the works in the exhibition are actually collaborations: Sōtatsu worked frequently with, among others, the calligrapher Honami Kōetsu to produce painted scrolls, screens, and poetry cards. Featuring literary tales and even popular songs of the time, the results are more than just illustrated texts; Sōtatsu’s gold-and-silver pigments invigorate Kōetsu’s fluid, black lines, while Kōetsu’s wavy characters fill spaces like wisps of smoke, dancing in the air to create a subtle rhythm.

This relationship with Kōetsu, whom modern collectors from the East and West regarded highly, is one reason Sōtatsu has managed to emerge from the shadows. Interest in Sōtatsu’s work, as Professor Ryo Furuta writes in the show’s catalogue, exploded in April 1913, when the Japan Art Association organized a retrospective. From Making Waves, it’s clear to see why Sōtatsu reemerged with such force: through his elegant expressions of ink and skilled manipulation of material, the painter transformed everyday paper objects into mesmerizing compositions that still shine centuries after their creation.

![(Artist) Tawaraya Sotatsu; Japan; 17th century; Ink, color, gold, and silver on paper; H x W (overall [each]): 166 x 369.9 cm (65 3/8 x 145 5/8 in); Gift of Charles Lang Freer](https://hyperallergic.com/content/images/hyperallergic-newspack-s3-amazonaws-com/uploads/2015/12/1-f1906-232-l.jpg)

Sōtatsu: Making Waves continues at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (1050 Independence Ave SW, Washington, DC) through January 31.