The Moment Caravaggio Became Caravaggio

What can an early painting tell us about an Old Master? We asked the Morgan Library’s curator to find out.

Certain artists arrive to us fully formed. The Baroque artist Caravaggio — iconic for his dramatic chiaroscuro and stormy disposition — is certainly one of them. I’ve always wondered about that process of canonization: Would a Caravaggio really stand out in a room of lesser-known contemporaries?

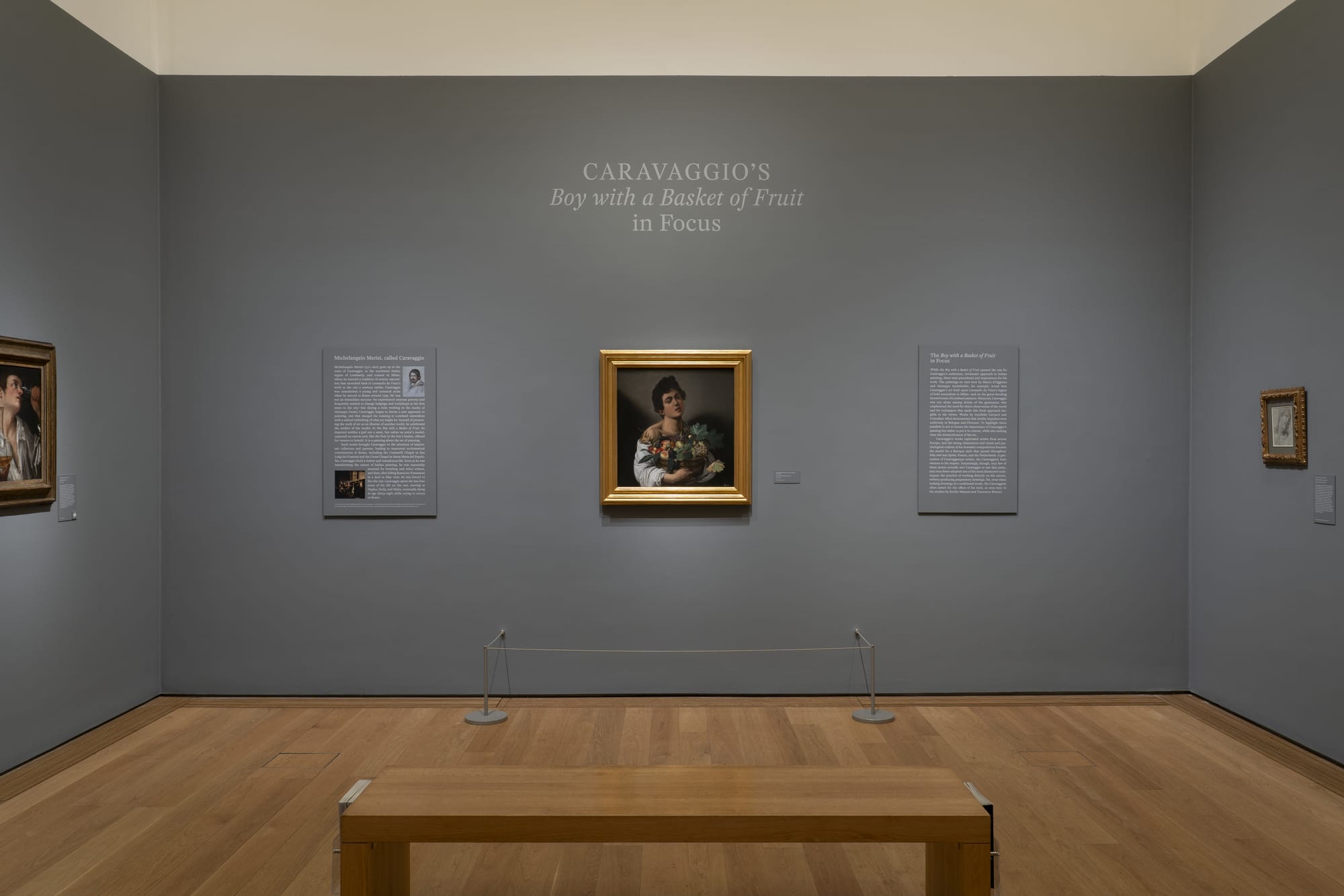

My visit to the one-room exhibition Caravaggio’s “Boy with a Basket of Fruit” in Focus at the Morgan Library & Museum suggests: Yes. The painting is modest in size — a little more than two feet (~61 cm) across — smaller, even, than some of the works that surround it. Its lighting isn’t dramatically different from the others. And yet it has this immense gravitational force.

Michelangelo Merisi, as he was known then, painted “Boy with a Basket of Fruit” in around 1595, when he was an early-20s unknown from the provinces outside Milan, training in the factory-like workshop of Giuseppe Cesari. The painting was, in a way, about nothing and for no one. It was not a commission, as most works at that time were, nor did it depict a god or an allegory, like many contemporaneous artworks. It is just a painting of a boy, holding this basket bursting with almost overripe fruit, his shirt slipping off his shoulder, looking past but not through you, the subtlest modulation in those dark eyes.

Hyperallergic talked to curator John Marciari, who has been with the Morgan for 12 years, about the process of putting together a show on 400-year-old art, the surprisingly modern gallery system that Caravaggio frequented in Rome, and what this early painting can tell us about an Old Master.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Hyperallergic: Why do you think Caravaggio continues to captivate us today?

John Marciari: He fits the post-Romantic paradigm of the bad boy artist: He’s always in trouble with the law. He kills a man. He spends the last four years of his life on the run. He dies tragically early, but becomes this mythical figure whom everyone copies thereafter. That’s like every movie about an artist that’s ever been written. I think on that level, he remains popular because he’s accessible — he falls into a familiar trope.

The same reasons that his paintings were so important in their time — their immediacy, their effectiveness, the way they connect to a viewer — make him interesting and appealing even to people who don’t otherwise look at old paintings so much. That’s not an accident. What he’s trying to do is shatter that barrier between the world of the painting and the world of the viewer. He’s not painting a boy posing with a basket of fruit. He’s painting the fiction of the studio — the fiction of painting.

H: Tell me about “Boy with a Basket of Fruit.” What draws you to it?

JM: I think you’re meant to start with the basket of fruit — it’s like right there in your face! And there’s something overripe about the fruit — the figs are splitting — which is sort of the conceit of the whole painting. It’s held by this boy who’s got this expression — tilting his head, his lips parted. What’s he saying? How are you meant to read that expression?

That ambiguity makes the picture come alive. And if you look closely, his ears are red and hot, his face slightly flushed. It’s the equivalent of being overripe. He’s tired of holding the damn fruit and he’s been made to sit there for too long in a hot room, in late summer — you know this because of the kinds of fruit — and you can imagine it being 90 degrees in an airless studio. It calls attention to itself as a real act of a painter copying a thing in front of him.

This is the great joy of having a picture like that here. You know, I stick my head in that room and go look at it a few times a day. It’s like living with the painting for three months.

H: It’s amazing. You kind of get to have this masterpiece in your — it’s not your house, exactly —

JM: I think I spend more hours per day here than I do in my living room.

H: Give us a peek behind the curtain. What are some things about the process of curating a show like this?

JM: One of the things about working on art that happened 400 years ago is you never have the whole story. You piece together evidence from the few documents and the few writers who give biographical accounts. But the people who write about artists’ lives at the time are also telling tales. What can you know — or what can you think — if you don’t have the smoking gun of a document that says it?

Well, you’ve got the pictures as evidence. Pictures and drawings where you see the artists working out problems. Some of [this process] is speculative, but it’s not pure imagination. It’s proposing likely scenarios based on the fragmentary evidence we have.

H: How did this particular show come to be?

JM: This project begins with our partnership with the Foundation for Italian Art and Culture, whose mission is to bring great works of Italian art to American museums. We arrived at the possibility of borrowing “Boy With a Basket of Fruit.” For me and many others, it is a sort of signal work. It's the moment when Caravaggio becomes Caravaggio. It’s one of those epochal, revolutionary works where an artist comes into something new.

I could have put the painting with three benches in a room, and people would’ve been delighted. But it offered the possibility of doing something more interesting. He’s a painter people don’t think about in relation to much else because he’s such a complete figure in himself. But there’s more to the story — he doesn’t spring out of nowhere. He builds on a significant legacy of painting.

What we like to do at the Morgan is tell stories. So I thought, rather than just celebrating Caravaggio, it’d be interesting to put this picture in context — where he comes from, how immediate and powerful his influence is on other artists in Rome.

[Arcimboldo’s “Four Seasons in One Head” c. 1590] from Washington is done precisely at the moment when Caravaggio is a student artist in Milan, and everyone in Milan is talking about the painting — it’s in all the commentary of the time, so it’s impossible he didn’t know it. So I asked myself: What does Caravaggio take away from it? It’s the question of: How do you push the limits of what a painting is? It doesn’t have to be the same old set of gods, goddesses, allegories. You can have a painting that’s, in a way, of nothing. I think those are all questions that are fundamentally a part of Caravaggio’s makeup as he goes to Rome and paints “The Boy with a Basket of Fruit” on spec.

H: Wait, “on spec”? What do you mean by that?

JM: So that’s another interesting part of the story. Up to that time, the overwhelming majority of art was made as a commission. Young artists come to Rome and put themselves in the workshop of someone else. In the workshop of Giuseppe Cesari, Caravaggio paints the "Boy with a Basket of Fruit.” He’s this 23-year-old kid from the provinces that no one’s heard of.

But there’s a shift that’s happening in Rome just at this moment — the 1580s, ’90s, and then on into the new century. Just in that generation, in Rome, for the first time, there’s a pretty active art market where painters make paintings, and they put them on sale with dealers, and people can walk into a shop and buy them.

Think about a young artist in a new city trying to do something that’s going to attract attention and help him find patrons and clients and commissions. It’s an environment that leads to experimentation as a way of distinguishing yourself — especially for someone with Caravaggio’s temperament.

The painting does not sell.

H: I’m picturing being in Chelsea and just walking into all of these galleries. Was it like that? Would I have walked into a gallery in Rome and seen a Caravaggio?

JM: Sort of, yeah. I think you have to think about Rome in 1595. Everyone was going to Rome, because that’s where the new stuff was happening — all the new fountains and all the new palaces. It was unlike any other city in the world. But it’s more like New York in 1960 or ’65 than now. Most of the galleries in Chelsea are sort of empires compared to the picture dealers of 17th-century Rome. It’s all very local.

H: I’m fascinated by this idea of this work being an Old Master’s first masterpiece. Are there elements of it that mark his developing style? Or anything he’s trying out and then abandons?

JM: Oh, absolutely. Again, on the one hand, this is a picture of nothing — not a god, not an allegory. No one knew what to make of that in Rome at the time. The next painting he makes is this self-portrait of Bacchus, where he’s sick. It’s like you can hear Caravaggio saying, “What? You can’t complain that the picture isn’t of a god. Here, I’ll give you a god. I’ll put an ivy crown on and call myself Bacchus.” But it’s obviously Caravaggio — and Caravaggio at his least godlike, after spending weeks in the hospital sick with an infection in his leg.

And then he goes on and does “The Boy Bitten by a Lizard” [1594–96], because another one of the criticisms would be that he just paints what’s in front of him. And it all comes together with the “Bacchus” from the Uffizi [c. 1595–97], where it’s a god, but not a god: It’s a boy posing as a god, reclining on a dirty bed, holding a glass of wine with ripples in it — so you get motion, but in a very subtle way.

Now here, [in "Boy with a Basket of Fruit,"] the foreshortening of the arm is a little bit fudged, the musculature of where his shoulder connects to his clavicle connects to his neck. He’s not a perfect artist, yet. We can track a sequence — one that begins with the “Boy with a Basket of Fruit.”

Editor's note 1/30/26 4:19pm EST: A previous version of the article dated Caravaggio's "Boy with a Basket of Fruit" to circa 1593. More recent scholarship dates the painting to 1595. The interview has been updated to reflect this fact.