The Myth of Beyoncé and Pop Cultural Liberation

The argument is that Beyoncé’s “Formation” is complexity masquerading as simplicity. But it’s also simplicity pretending to be more complicated.

So Beyoncé performed at the Super Bowl this past weekend and, some say, clearly articulated political views that diverge from the mainstream, putting forward an idea of blackness as separate from a touchy-feely, well-meaning idea of universal togetherness conveyed by fellow performers Coldplay.

Zandria F. Robinson says that Beyoncé expressed a Southern Blackness that can’t help but evoke thinking about other kinds of blackness, “at the blackness margins — woman, queer, genderqueer, trans, poor, disabled, undocumented, immigrant.”

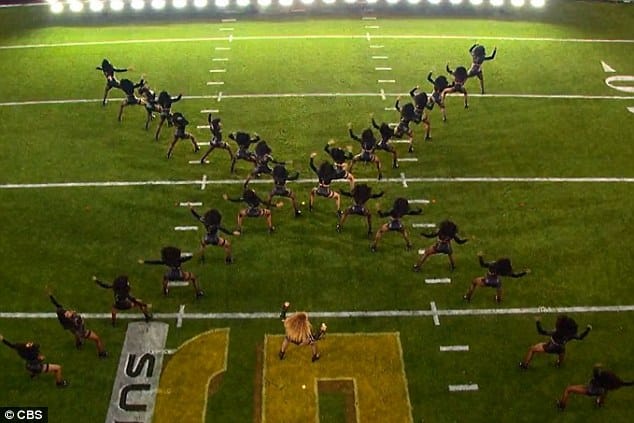

Naila Keleta-Mae says that Beyoncé delivered, under the cover of a catchy, sexy pop song, a complex meditation on female blackness. So if Keleta-Mae is correct in this, then Beyoncé snuck some radical ideas in the trunk of her pop vehicle. Mostly Super Bowl entertainment is focused on big, spectacular performances, glitzy visuals and sublimated sexual desire. Beyoncé’s was all of this: Queen Bey at the head of a phalanx of curvaceous black women dressed in black, leather or vinyl boy shorts over fishnet tights with one garter on the right leg, long-sleeved crop tops, a beret cocked to one side over big, blown out kinky hair — all dancing in black boots with heels in seamless synchrony, as a bank of pyrotechnics exploded in fire behind them to punctuate their movements.

The argument is that Beyoncé’s “Formation” is complexity masquerading as simplicity. But it’s also simplicity pretending to be more complicated.

Beyonce's dancers paid tribute to #MarioWoods, black man killed by San Francisco police. #SB50 #BlackLives pic.twitter.com/m2Pl9i5qKL

— Jamilah King (@jamilahking) February 8, 2016

Just take the use of the Black Panther signifiers of the afros, berets, and raised fists — these are supposed to stand in for the revolutionary politics of a historically distinctive group that confronted the state and fought to establish social and political equality in ways previously unheard of. Started by Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in 1966, as the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, its members directly challenged police authority; established socialist, community-based frameworks such as the Free Breakfast for School Children program that eventually fed over 10,000 children a day; grew to the size where they had offices in 68 American cities, and an international chapter operating in Algeria; vehemently and insistently opposed segregation and the draft, and were even called “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country” by the then FBI Director. Essentially, they, for all of that pivotal decade that brought racial and gender politics to the forefront of our consciousness, the Panthers were the pointy end of the spear that was the black liberation struggle in the US. All of this ferociously wild history is then shrunk down to some style choices and this is considered empowering?

So Che gets reduced to a poster, the renegade figure of Malcolm X to a choreographed arrangement, the struggles against AIDS to a song, and concerted, protracted protest to a hand signal for peace. This is what pop culture does. It’s about giving us the whiff, the suggestion of something that has a very high price tag that someone else paid for. The video for “Formation” even acknowledges this with an image and caption of Martin Luther King that denies that silly “dreamer” moniker. Yes, this is what pop culture does, but that doesn’t mean it’s useful or we need to value it for that.

The politics of the image convened around Beyoncé and her videos are really centered on the politics of a heroic individual. This politics trump every other politics in this instance. This work is not really a meditation on blackness. It’s a meditation on Beyoncé, who is a more than a star; she’s a constellation of talents. Keleta-Mae again says: “And what that choreography reveals is the embodiment of a particular kind of 21st Century black feminist freedom in the United States of America; one that is ambitious, spiritual, decisive, sexual, capitalist, loving and communal.” This idea of freedom is really a kind of myth that gets projected onto an actual person who seems able to carry it forward — the kind of super-woman who Beyoncé certainly seems to embody, but few other people do.

The issue with this hope, this fantasy is that it ignores its own internal contradictions: I mean how spiritual is it to aspire to wear Givenchy, and is that what people should be ambitious about? How does one tell the difference between the loving and the decisive sexuality that just may be spurred on by the profit motive?

The problem here is that the worship is not really of Beyoncé but rather, of the myth she stands for: the woman who can do it all: rule, slay, date, make a profit, and in the popular imagination this myth ends up being reduced to simplistic cultural algorithms that don’t ultimately compute. To be clear: politics for me are more or less relations of power. There are many kinds of power and they can be refracted through a variety of human practices and ways of seeing. So, yes the “Formation” performance was political, especially the moment when the “Formation” dancers, impelled by members of the Black Lives Matter movement, acknowledged the death of Mario Woods by the hands of police. This was all certainly political, but not particularly radical.

The video and performance of “Formation” is about Beyoncé, but she herself is just a stand-in for the dream of a blackness that encompasses everything. Swallows up all the contradictions of being enslaved yet being survivors; being oppressed yet being originators; being irresistibly sexy and yet being ignored at times; being hybrid and yet being authentic. We go to the well of pop culture for easy cultural signifiers and simple identifications because they give us a break from parsing all the things we have to parse just to cross the street. And, also because we want so damn badly to be free.