Tribeca Galleries Discuss Reporting Street Vendors, Drawing Criticism

A group of galleries met to address the “increased number of vendors” on and near Broadway, many of whom are immigrants under threat.

Today, January 30, art galleries and cultural organizations across the country are shuttering in solidarity with immigrants amid violent crackdowns. Many public gestures of support are unfolding in New York City, but two weeks ago, a group of Tribeca galleries met to discuss asking the city to address an influx of street vendors in the area, Hyperallergic learned.

On January 15, months after federal agents descended on Canal Street in a targeted vendor raid, representatives for a group of galleries near Lower Manhattan’s Canal Street met at Alexander Gray Associates to discuss “safety” and “accessibility” issues associated with local street vendors on Broadway, according to communications obtained by Hyperallergic.

An email sent to local galleries by a PPOW staff member tasked with taking notes for the meeting encouraged galleries to file complaints with 311 to “increase the likelihood of a response” from the city. Gallery representatives who attended, according to the email, discussed drafting a letter “asking for support” related to street vending, which would later be sent to city officials.

“A few of us got together yesterday to initiate a conversation regarding the issues of safety and accessibility associated with the increased number of vendors on Broadway (and the surrounding area) and agreed that the best course of action is to address the city as a unified group,” the email said.

When reached for comment, PPOW’s management told Hyperallergic that the gallery was not leading the effort, and that one of its employees attended a meeting at Alexander Gray Associates to take notes as a “courtesy.” PPOW denied calling 311 on vendors and disavowed the email’s suggestion that others do so.

“An unapproved email with views that directly undermine our mandated values of the past four decades was sent out by one of our staff members to the Tribeca community,” PPOW directors Wendy Olsoff and Penny Pilkington said in a statement. “What is in line with PPOW’s values as a gallery is to acknowledge responsibility, learn from our mistakes, and collaborate with artists and community leaders to educate our staff and grow from this experience.”

Olsoff and Pilkington said they plan to “bring in NYC vendor rights groups to teach us how to support migrant vendors outside our doors.”

In the initial email circulated between the Tribeca galleries, they agreed to meet again on January 27, but a spokesperson for PPOW and Alexander Gray told Hyperallergic the meeting had been postponed.

In response to a request for comment, Alexander Gray said that he had offered his namesake gallery as a meeting place “when some community members were looking for a space to meet.”

“Over the past year, neighbors along lower Broadway have been discussing mobility challenges on the corridor,” Gray said in an email to Hyperallergic. “Increasingly, sidewalk congestion has made it difficult for individuals in wheelchairs, elderly residents, families with strollers, and others to navigate the area.”

Gray said the gallery “oppose[s] ICE enforcement practices and any actions that harm immigrant communities.” Gray did not respond to a question about whether he had filed 311 complaints against the vendors.

“The goal has been to help articulate shared concerns so that the city, which manages public sidewalks, can advise on equitable solutions that work for everyone, including vendors,” Gray said.

According to a publicly available spreadsheet reviewed by Hyperallergic, 12 Tribeca galleries expressed interest in “joining the next meeting or signing the letter once it is ready.” Among those listed were Nino Mier Gallery, anonymous gallery, Marian Goodman, Andrew Edlin Gallery, Andrew Kreps Gallery, Asya Geisberg Gallery, DIMIN, Matthew Brown, Michael Lisi Contemporary Art, and Tara Downs.

In response to Hyperallergic’s inquiries, representatives for Marian Goodman, anonymous, and Nino Mier galleries all said that while they listed their names to receive information about efforts, they had not taken action and did not necessarily support the suggested initiatives. After publication, Asya Geisberg told Hyperallergic that she had removed her gallery from the spreadsheet and that the gallery had not filed any complaints. Tara Downs said that “the meeting administrators added our name to the list, and we removed it,” and that “it does not reflect the gallery's outlook.”

Hyperallergic has not yet heard back from the remaining galleries.

According to a 2024 report from the nonprofit Immigrant Research Initiative, nearly all of New York City’s street vendors are immigrants, primarily from Mexico, Ecuador, Senegal, and Egypt. Undocumented immigrants are also more likely to sell food and general merchandise without the permits required by the city, the report said.

Just a few months before gallery representatives met, ICE arrested nine immigrants from West Africa on Canal Street after a Turning Point USA influencer posted that undocumented vendors were allegedly selling counterfeit goods in the area. Since then, some migrant vendors, who rely on income from selling goods on the major thoroughfare to survive, have reported fearing future raids. At a municipal level, the New York City Police Department has also made arrests in the area following complaints of street congestion.

Gray’s stated opposition to harmful enforcement practices echoes the position of the area’s City Council representative, District 1 Councilmember Christopher Marte, who has called for stricter enforcement of vending regulations on Canal Street but condemned ICE intervention. According to New York City's sanctuary city laws, police and city agencies are restricted from cooperating with federal immigration agencies. The primary agency enforcing vending regulations, the Department of Sanitation, does not collaborate with federal immigration agencies, a spokesperson told Hyperallergic.

But even with sanctuary city laws in place, intervention by municipal agencies could lead to federal engagement, explained Mohamed Attia, managing director of the Street Vendor Project, which advocates for the rights of street vendors in New York City.

Attia told Hyperallergic that NYPD still issues criminal tickets to vendors, placing them in danger of arrest — and possible ICE targeting — if they do not show up to their court date for any reason.

“We talked to a lot of individual lawyers and confirmed that once you are arrested, you are in the system, all enforcement agencies across the nation will see your data and will have your information,” Attia said.

While the NYPD hasn’t led street vendor enforcement since the beginning of the Adams administration, the agency has apparently responded to complaints about street congestion in Lower Manhattan, arresting vendors and confiscating goods. Multiple city departments, including the NYPD, can issue citations for vending violations, according to Attia.

The Department of Sanitation has its own armed police force, indistinguishable in appearance from NYPD officers except for a badge, Attia noted.

“It's really sad to see businesses attacking the street vendor community because the vendors are also small businesses,” Attia said in response to the news that galleries considered engaging the city to address increased vendor presence.

News that galleries had met to discuss street vendors and city intervention outraged some in the arts community. Cindy Hwang, a member of the Lower Manhattan anti-gentrification group Art Against Displacement, told Hyperallergic that she wished businesses would consider alternative ways to address vendor-related issues.

“There are so many ways to improve street life that don’t involve the NYPD, which actively facilitates federal immigration enforcement,” Hwang said.

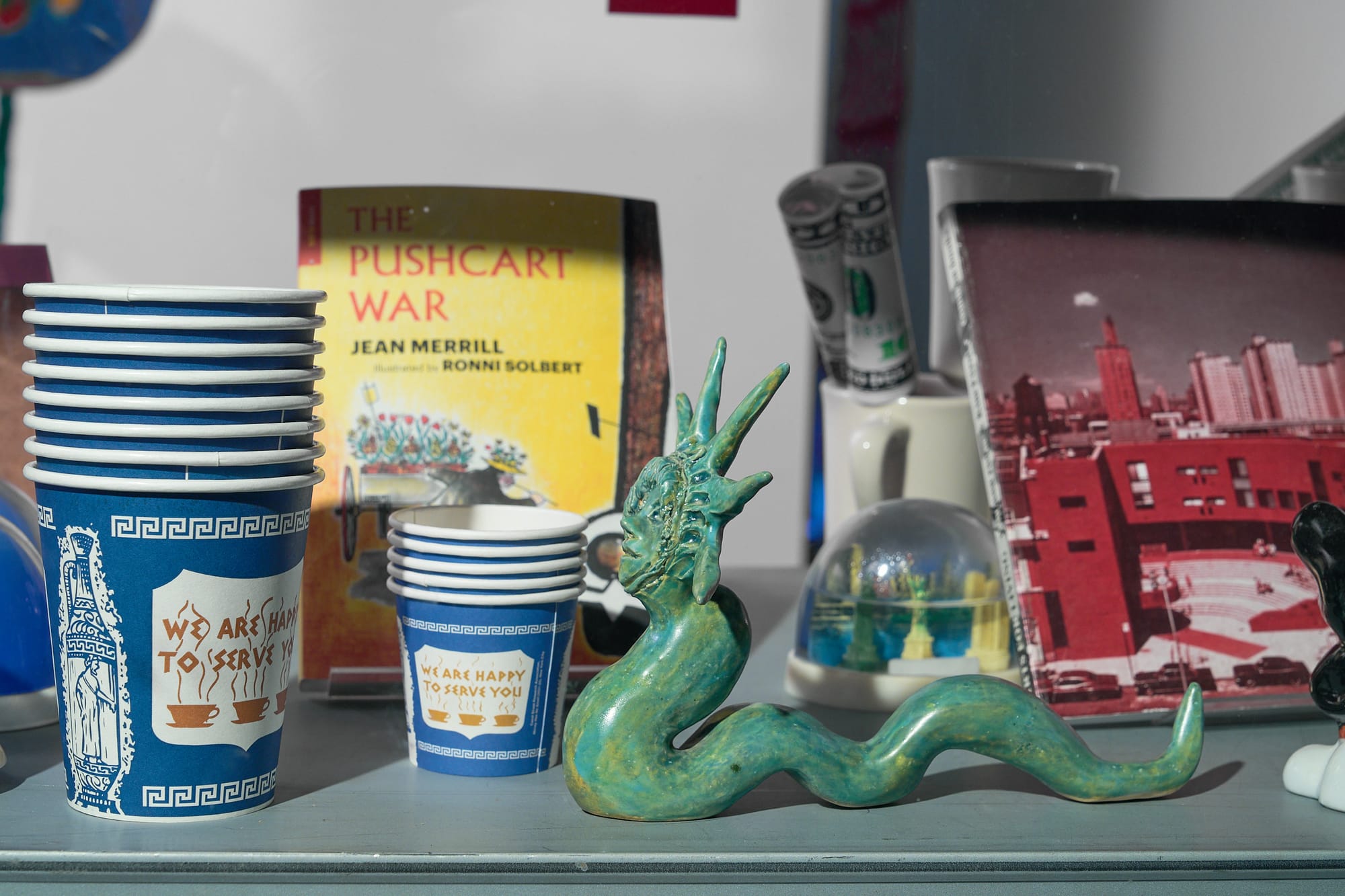

Artists Ming Lin and Alex Tatarsky, co-founders of the art collective Shanzhai Lyric, are behind the conceptual project Canal Street Research Association, which explores the area’s immigrant-run street markets and interrogates ideas of property and authorship.

During a panel discussion at Essex Market on Thursday, Lin and Tatarsky traced the criminalization of street vending to Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s “War on Pushcarts” in the 1930s, when LaGuardia declared unlicensed peddlers a risk to traffic and sanitation.

“Street peddling has always been the art of those unable to own property, one of the few ways for folks with limited resources, often immigrants, to have some financial autonomy and the possibility of upward mobility without the exorbitant rent,” Tatarsky said.

In a statement to Hyperallergic, Lin and Tatarsky described vendors on Canal Street as “excellent neighbors and great colleagues on the block.”

“It really disgusts us that some galleries would complain of safety concerns when the vibrant, and yes, sometimes hectic, street markets are a beloved and long-standing part of the neighborhood ecosystem and character,” Lin and Tatarsky said. “This feels especially abhorrent at a moment when vendors currently face serious threats from both NYPD and ICE.”

Even without city or police intervention, vendors face obstacles to obtaining permission to sell. New York City requires a general vendor license to sell certain non-food goods in public, and currently issues only 853 of these licenses to non-veterans. Despite the cap on licenses for non-veteran merchants, the Immigrant Research Initiative estimates that there are 2,400 such vendors operating throughout the city. Fines for operating without a license are steep, starting at $250 and increasing with each repeat violation.

Shamier Settle, a senior policy analyst for the NYC-based Immigration Research Initiative, told Hyperallergic in an email that there is currently a long waiting list for vending licenses and that applicants must have Social Security or taxpayer identification numbers.

On Thursday, City Council approved a bill to increase the vending license cap to 10,500 general vending permits by 2027, a measure previously vetoed by the Adams administration.

Today, Friday, January 30, a number of galleries, including PPOW, Marian Goodman, and Pace, closed their doors in solidarity with a national anti-ICE economic shutdown. But galleries' participation in the strike, highly publicized on Instagram and elsewhere, raises questions about how arts organizations can effectively support local immigrant communities year-round.

“It is a shame that so many art spaces capitalize on and claim to value the ‘gritty’ history and character of SoHo, Tribeca, and Chinatown while actively working to threaten the lives and livelihoods of the mostly immigrant vendors who make Canal Street such a special place,” Lin and Tatarsky said.

Attia said he believed that if galleries voiced their concerns directly to vendors, some of their issues would be addressed.

“I really hope that these galleries and these businesses reach out to the vendors, build up a relationship with them,” Attia said.

Valentina Di Liscia contributed reporting.

Editor's note 1/31/26 11:30am ET: This article was updated with a response from Asya Geisberg Gallery and Tara Downs.