What It Is to Be Cool in America

What is cool and why do Americans care so much? That's the hinge on which the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery has fixed American Cool — an exhibition of portraiture that opened in February — and its accompanying catalogue.

What is cool and why do Americans care so much? That’s the hinge on which the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery has fixed American Cool — an exhibition of portraiture that opened in February — and its accompanying catalogue.

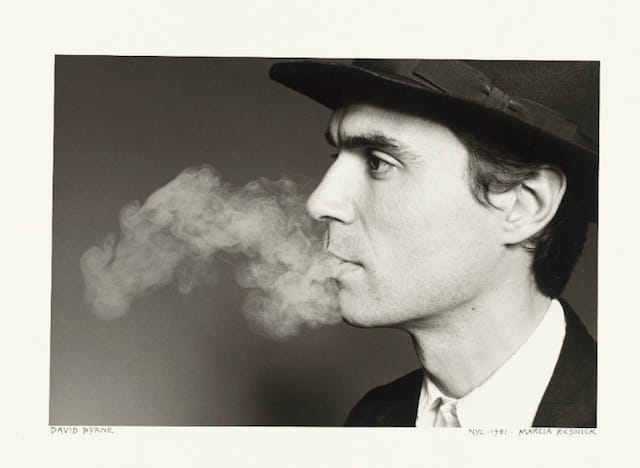

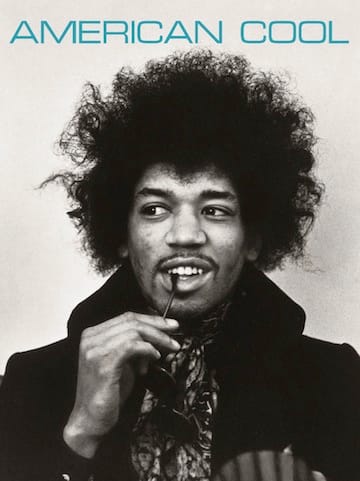

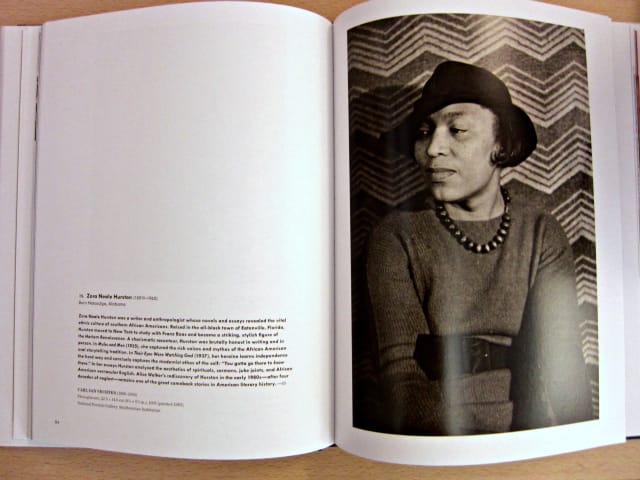

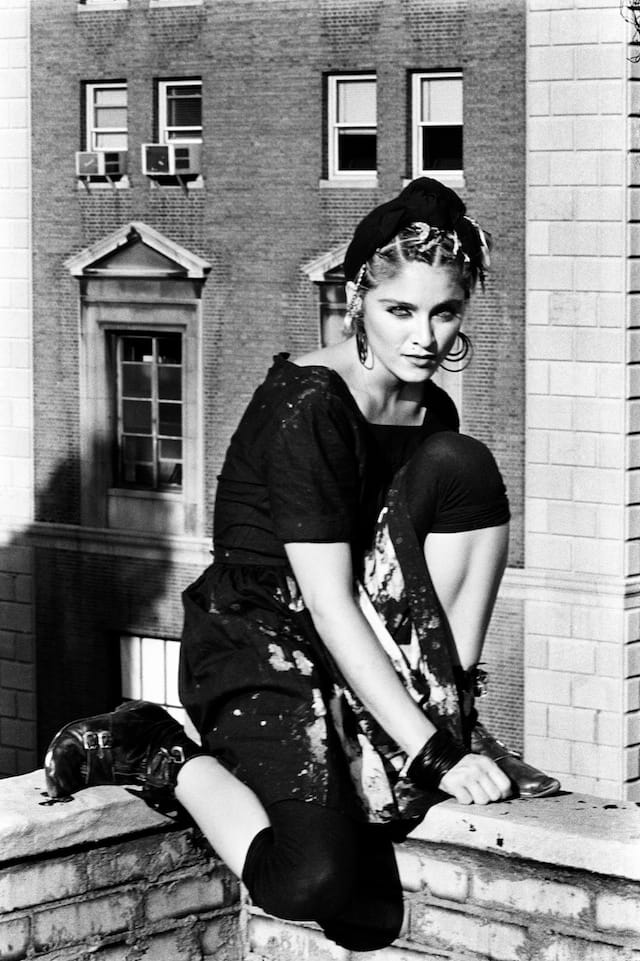

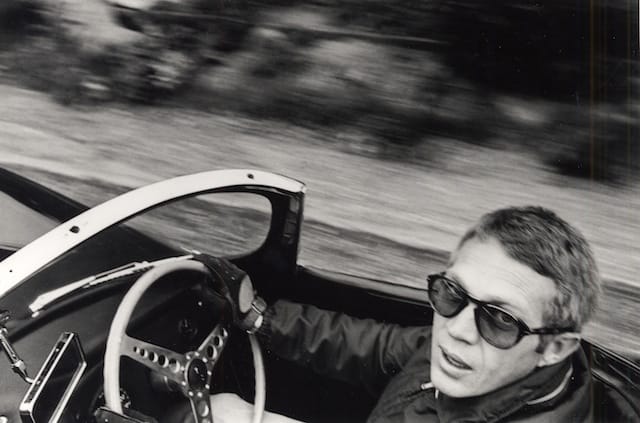

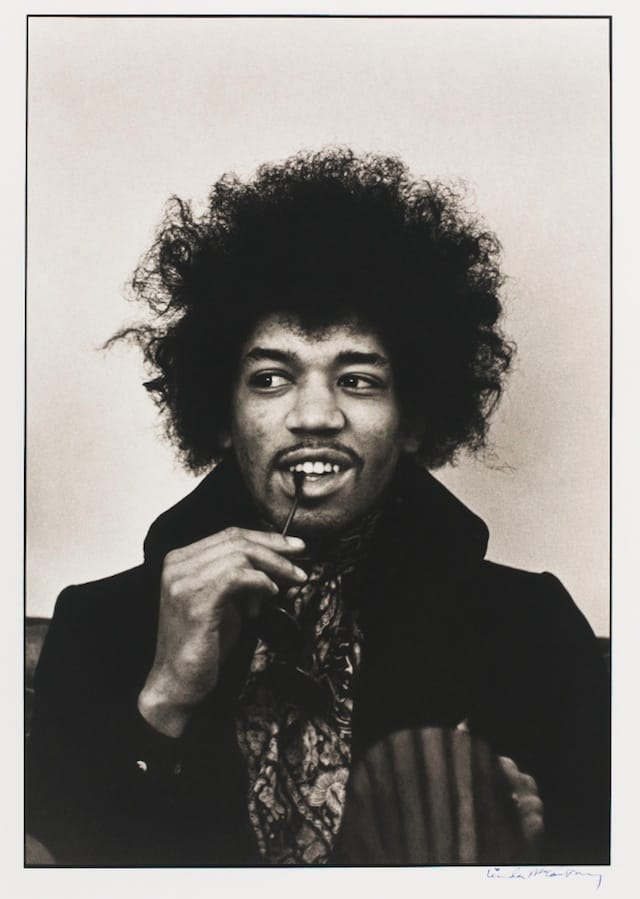

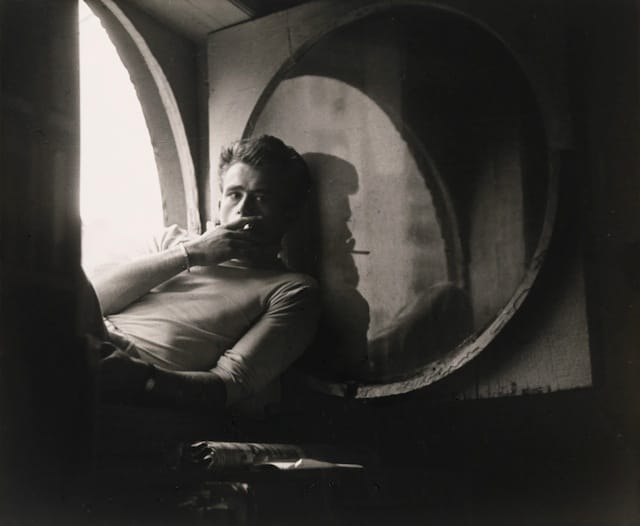

Published by Prestel, the photography book includes essays by curators Joel Dinerstein and Frank H. Goodyear III who delve into all the vague questions about this most coveted of attributes. Just 100 figures have been selected, all of them celebrities, all seductive in some way, with James Dean, Hunter S. Thompson, Barbara Stanwyk, Missy Elliott, Raymond Chandler, Bessie Smith, Jimi Hendrix, and even Frederick Douglass captured in ambrotype, gazing away from the 19th century lens with early aloofness.

What all these people have in common, aside from being famous, of course, and having a fondness for the coolness of cigarettes as many of the portraits capture, is a bit hard to define. As to why select only those from the United States (aside from the fact it’s an exhibition at the US’s National Portrait Gallery), Dinerstein explains in the forward:

First, new cool personae mostly trickle up through popular culture, and American pop culture has functioned as something of a global lingua franca for more than a century. Second, a set of conditions for generational cool are often forged at the intersection of youth culture, popular culture, and African American culture, from swing to rock and roll to funk to hip-hop, from language to dance to fashion to aesthetics.

He also notes that, “cool figures are the successful rebels of American culture.” In this land, “to be cool is to have an original aesthetic approach or artistic vision — as an actor, musician, athlete, writer, activist, or designer — that either becomes a permanent legacy or stands as a singular achievement.”

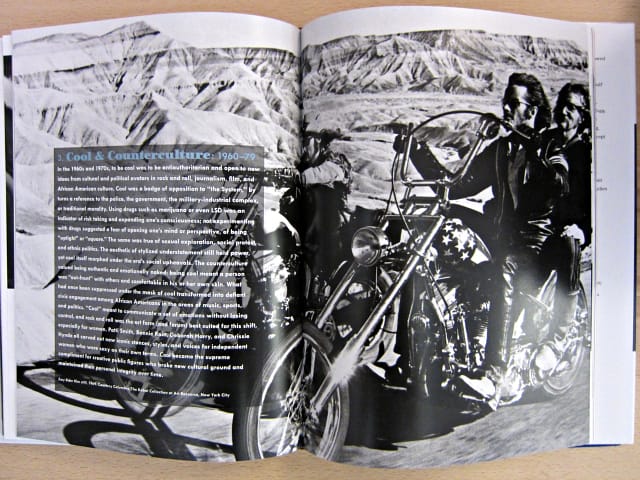

Like the exhibition, the book is segmented into stages like “The Roots of Cool: Before 1940” and “Cool & Counterculture: 1960–79.” Each of the icons are given little blurbs that attest to their coolness, and for Walt Whitman, who is represented by an engraving, Dinerstein writes that the portrait graced the 1855 edition of Whitman’s most famous book, Leaves of Grass: “He left his name off the title page and offered this image instead: a plain workingman, relaxed, hat cocked at a rakish angle, a bit arrogant, ready for anything.”

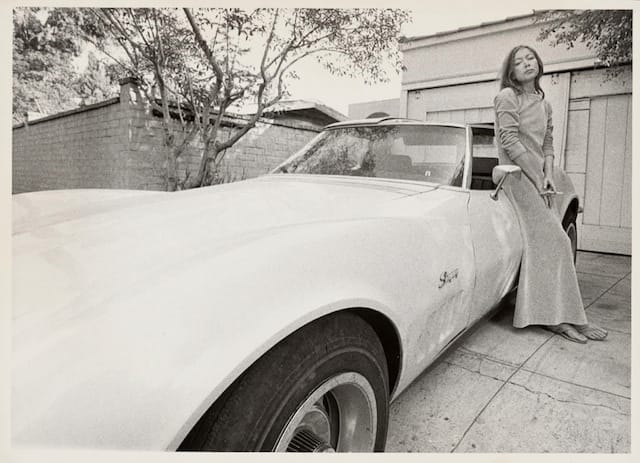

But despite the lone wolf of Whitman, it is photography that has defined much of what is perceived as cool. Goodyear emphasizes in his essay that photography “does more than simply document the cool aesthetic; it plays a constitutive role in making it real,” through permitting a public persona, developing a visual vocabulary of posture and expression, and offering a place to experiment. It also holds something aspirational for the masses, to examine in the carefully positioned poses just what about the mix of detachment and confidence is so desirable.

American Cool continues at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery (8th and F Streets, Washington, DC) through September 7. American Cool by Joel Dinerstein and Frank H. Goodyear III is available from Prestel.