A New Year, Same Type of Tired Corporate Critique

Ringing in the New Year, the Winkleman Gallery's group exhibition Corporations Are People Too might prove that 2011's artistic obsession with corporate power, the economic crisis, and abandoned office buildings with unintentionally ironic posters will continue into 2012. And I'm not entirely convinc

Ringing in the New Year, the Winkleman Gallery’s small group exhibition Corporations Are People Too might prove that 2011’s artistic obsession with corporate power, the economic crisis and abandoned office buildings with unintentionally ironic posters will continue into 2012. And I’m not entirely convinced that’s a good thing.

Taking its name from a typically stupid Mitt Romney quote, Corporations Are People Too traces the role of corporations in the lives of Americans from photographs of child labor during the Great Depression to Phillip Toledano’s photographs of empty offices from the early 2000s. Obviously inspired by the popularity of Occupy Wall Street, I fear that the Winkleman Gallery’s show foreshadows a year of similar gallery exhibitions that will attempt to latch on to the critique articulated by OWS.

When I first walked into Corporations Are People Too, I felt the distinct sense of deja-vu that I had attended this exact exhibition before. Probably because in the past year, there has been so much art dedicated to the economy, corporations and protest that there seems to be nothing new to be said. Eerily similar to the work that I saw in 14 & 15, an exhibition in an actual abandoned office space in the Lipstick Building this past summer, the work was, as a whole, as lifeless and distant as the corporations they are critiquing.

My main problem with these group exhibitions that focus on the economy is there never seems to be any real purpose to the work. At the end of the day, an exhibition that is curated based on the role of corporations in the lives of Americans from the 20th to the 21th century should probably seem to have an overarching statement or at least, make the visitor reconsider the role of corporations in their own lives.

For example looking Kota Ezawa’s series of Ikea lightboxes, which are redrawn from the catalogue itself, I feel that I’m missing the point. The Winkleman press release explains that these Ikea works:

stem from his mixed feelings about our need for furniture chosen not as an object to be kept or cherished but rather as an inexpensive solution to a living problem. Within these paired-down renderings, the catalog pages lose their function as advertisements and their staged domestic interiors become instead theater stages for the drama of contemporary life.

I’m not sure I buy that explanation. Maybe this has to do with my own reliance on Ikea to furnish my studio apartment, but what is furniture other than a solution to a living problem? Finding myself engaged in another struggle with a bad press release, I have a hard time finding the “theater stage for the drama of contemporary life” in “NEW! $2.99” (2007). Not that I would even know what that was if I saw it.

The funniest work in the show was a series of letters of acknowledgement to Russian artist Yevgeniy Fiks who donated a copy of Lenin’s Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism to 100 corporations’ libraries. Filling an entire wall of the gallery, these 34 letters are a hilarious read, yet after trying to elbow my way through the opening crowds to read the text, I questioned the point of this action. The letters also reminded me a little too much of Ted L. Nancy’s (who may or may not be Jerry Seinfeld) Letters from a Nut.

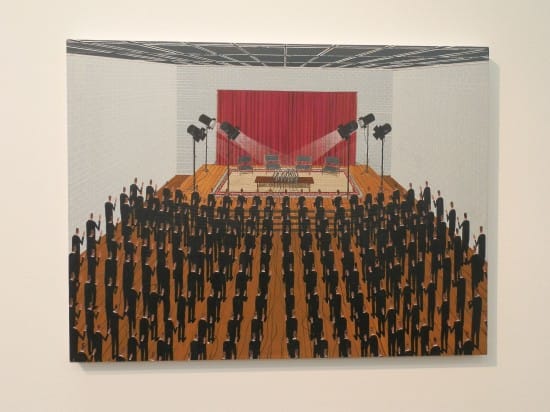

Perhaps the most successful works in the exhibition were the two paintings by Ian Davis depicting business people as suits without faces or any identifying feature like a mob of little Don Drapers from the television serial, Mad Men. Looking at “Conversation” (2011), I appreciated the humor in naming a painting conversation that represents a crowd of faceless men watching a stage with four chairs as if it were set up for a lecture. It appears to post the question, has a conversation become completely one-sided? Certainly, conversations between corporations and the everyday lives of Americans are set up in this manner. Davis’s critique of the definition of conversation could not only apply to these faceless corporations and drone-like workers but also to the power dynamics in many fields, such as academia.

Even though I enjoyed some of the work and even appreciated bringing corporate critique back to the early 20th century with photographs by Dorthea Lange and Bernice Abbott, I just left the exhibition feeling bored and in need of a Starbucks.

Corporations Are People Too will be at the Winkleman Gallery until February 4, 2012.