Yasuo Kuniyoshi Retrospective Places the Painter at the Center of Modern Art in the US

WASHINGTON, DC — In 1948, Yasuo Kuniyoshi was the first living artist to receive a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art and that was the last time his career was thoroughly explored before this year's exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

WASHINGTON, DC — In 1948, Yasuo Kuniyoshi was the first living artist to receive a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art and that was the last time his career was thoroughly explored before this year’s exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi chronologically retraces his art alongside the story of his life, as a Japanese immigrant in the United States restricted by xenophobia and labeled an “enemy alien” following Pearl Harbor.

“Even now, eighty or ninety years later, we must search carefully to find those points of apprehension in his art and life, but like dots on a graph they chart the backstory of this immigrant’s experience,” Elizabeth Broun, director of the museum, writes in the catalogue.

Arriving in the United States as a teenager in 1906, he soon adopted the country as his permanent home until his 1953 death in New York from stomach cancer. However due to immigration laws he was never allowed to receive citizenship. Despite not stating directly how being considered an outsider in the place he felt most at home impacted his art, The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi examines the parallels between the later more grotesque shapes and caustic colors as representative of this anxiety. Curator Tom Wolf writes in his extensive catalogue essay:

The many American writers who claimed there was something ‘Oriental’ about his art were right: he incorporated elements from Asian artistic traditions, in terms of technique, composition, and subject matter, into his art in many inventive ways. And he was right when he said, ‘Except for my physical appearance and my name I am just as much an American in my approach and thinking as the next fellow. I’m as American as the next fellow.’ But the fact he felt he had to exclude his physical appearance and his name acknowledged the dominant stereotype and suggests the pressures Kuniyoshi faced.

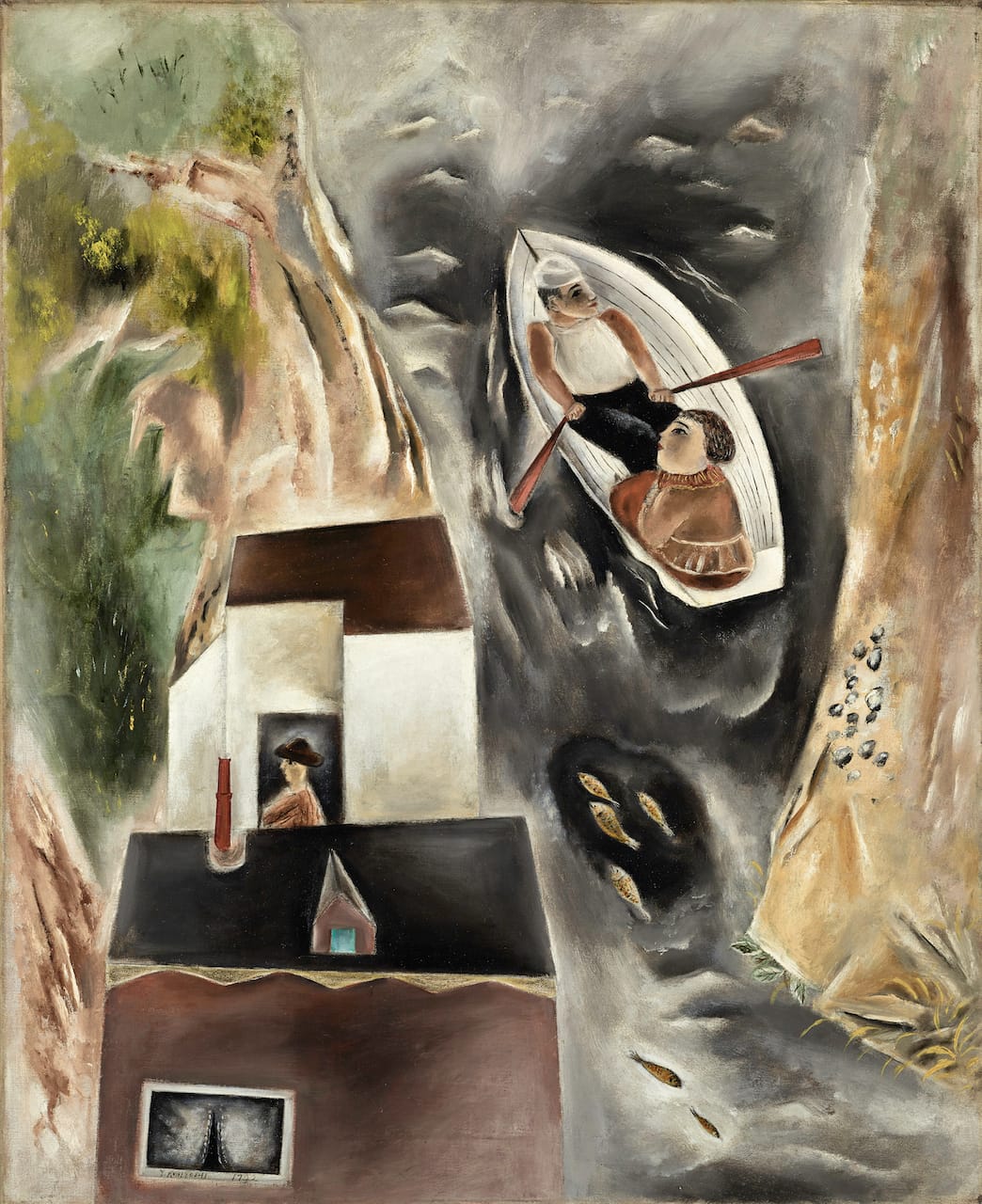

Kuniyoshi’s work was more widely known in the United States during his lifetime, with much of his posthumous interest shifting to Japan. The exhibition is a beautiful argument for celebrating him as one of the 20th century’s great American artists, in a museum devoted to that experience. He was a slow creator, with an estimated 350 completed paintings in his lifetime, and each of the 41 paintings and 25 ink drawings assembled from private and public collections is rich in detail and use of understated color palettes.

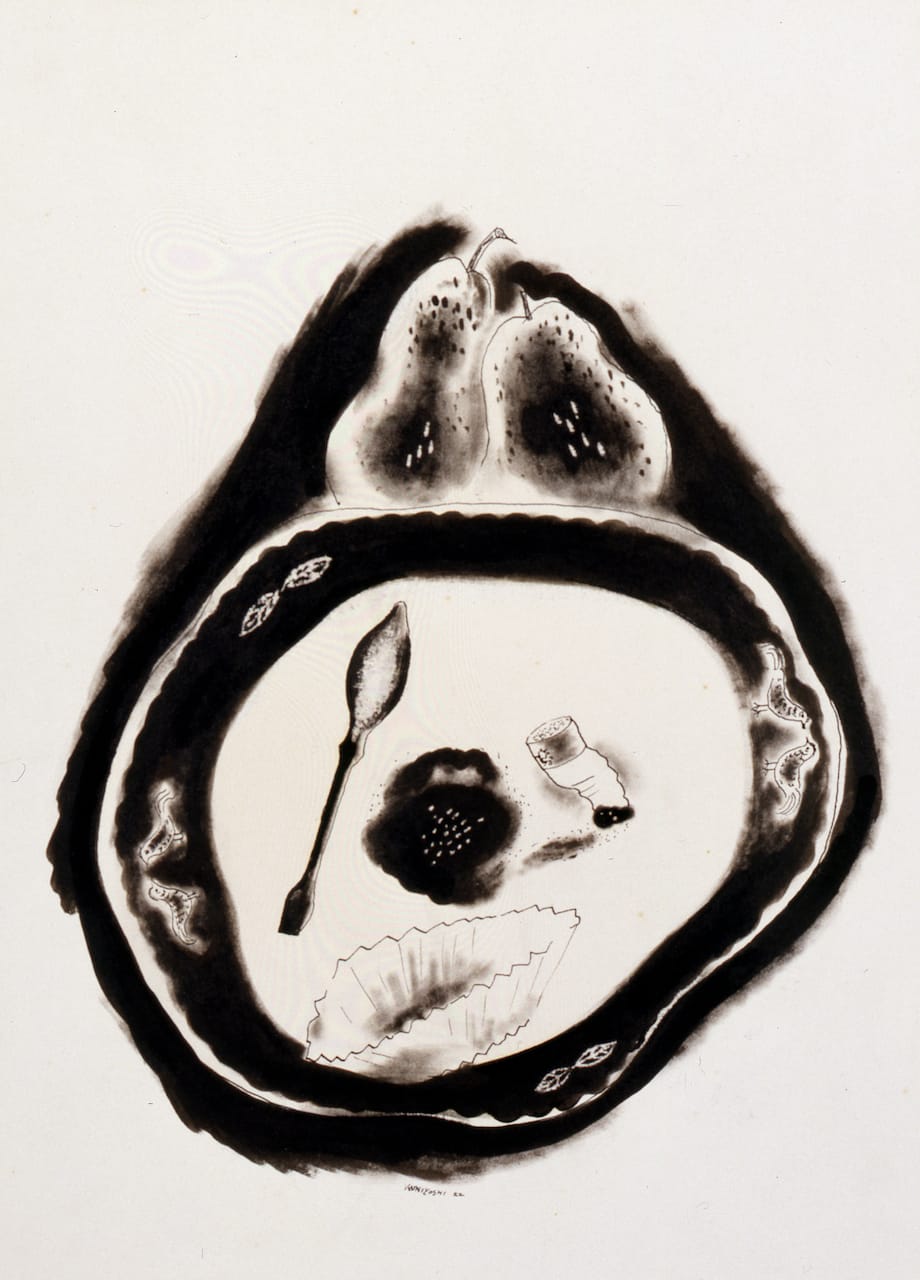

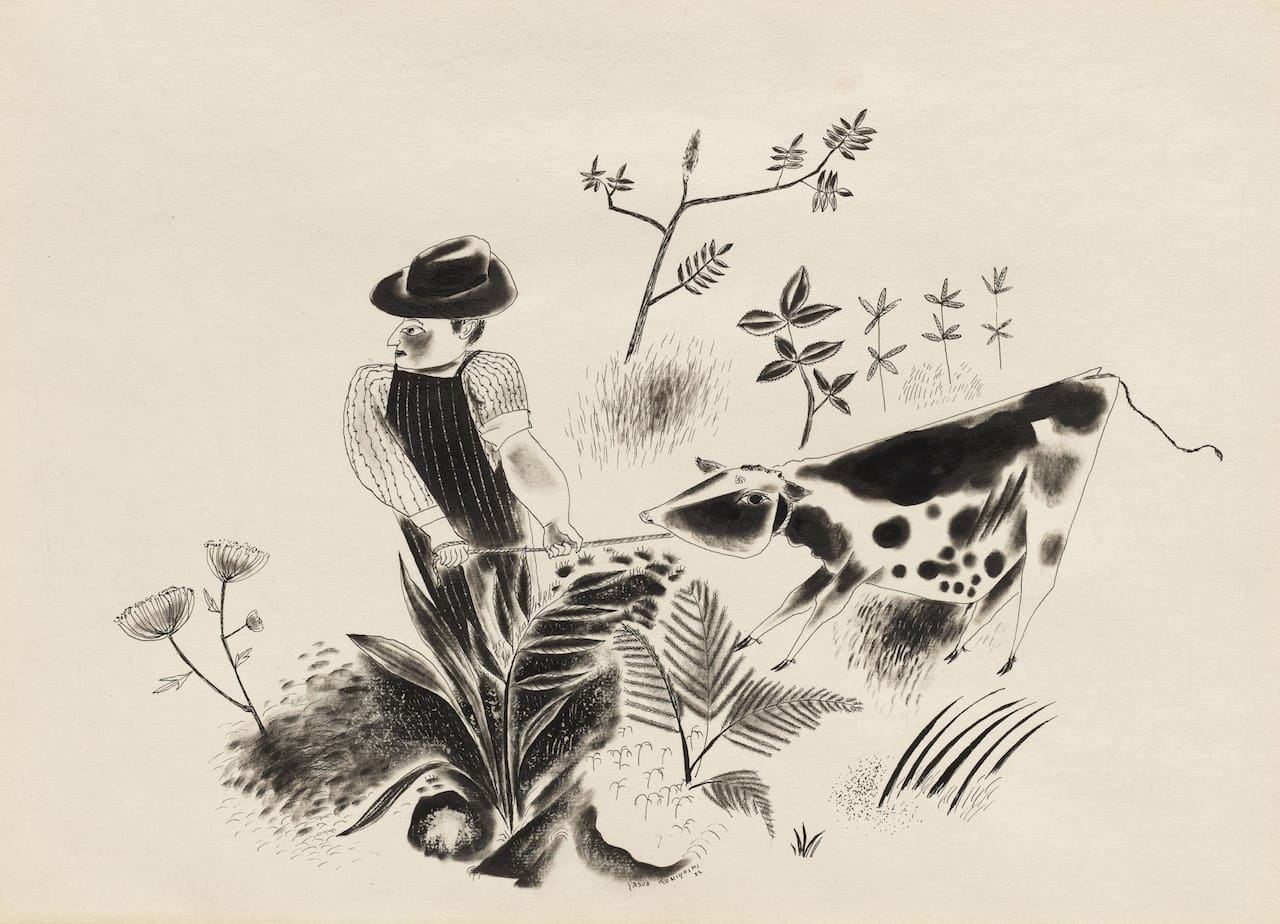

Early work in the 1920s, like “Boy Stealing Fruit” (1923), have dynamic contrasts between flat and dimensional perspective, distorting ordinary objects like a table and bowl, with some Americana influence. Cows graze through with gaping human eyes, possessing the kind of anthropomorphic personalities and sly humor of Chagall’s animals. Kuniyoshi also loved the circus, the strong ladies and other performers ready subjects for the playful proportions he gave his figures. Following the war, during which his movement was restricted and bank account frozen (although he avoided the internment camps for Japanese Americans by being on the East Coast), a darker tone permeated his canvases. In “Festivities Ended” (1947), a carousel horse is flipped over and a faded pennant garland twisted around its legs like a tripwire; a couple of people sprawled out in the distance by a deflated circus tent suggests a catastrophic collapse.

The exhibition is a lot to take in, but each work is rewarding, the modernism easily mixed with folk art and Japanese design in ways that are deceptively simple, and then there’s the imagery that evokes the stuff of dreams. It’s hard not to read into his work because of the wealth of symbolism and allegory. Some see the boy sneaking a peach from a distinctly Americana bowl in “Boy Stealing Fruit” as a reference to his 1919 marriage to Katherine Schmidt — Schmidt subsequently lost her US citizenship because of a 1907 law that forced all women to acquire their husband’s nationality upon marriage. And the agitated colors of his later work could possibly evoke a personal conflict for the artist as he weighed his sympathy for a nuclear devastated Japan alongside his love for his adopted country. The exhibition is totally clear on one thing: his work deserves wider recognition, and another 65 years shouldn’t go by before the next museum pays attention.

The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi continues at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (8th and F Streets, N.W., Washington, DC) through August 30.