Watching the Beats Grow Old

From 1953 to 1963 — a period that corresponds with the publication of his most celebrated works — Allen Ginsberg snapped photographs of his cohort of soon-to-be famous friends. These shots weren’t intended for exhibition; they were mementos, thrown in the back of a drawer. He unearthed them two deca

From 1953 to 1963 — a period that corresponds with the publication of his most celebrated works — Allen Ginsberg snapped photographs of his cohort of soon-to-be famous friends. These shots weren’t intended for exhibition; they were mementos, thrown in the back of a drawer. He unearthed them two decades later and had copies made, in the borders of which he scrawled relevant details in felt-tip pen. It is these photographs, amended with shots from the ’80s and ’90s, that are on display at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery.

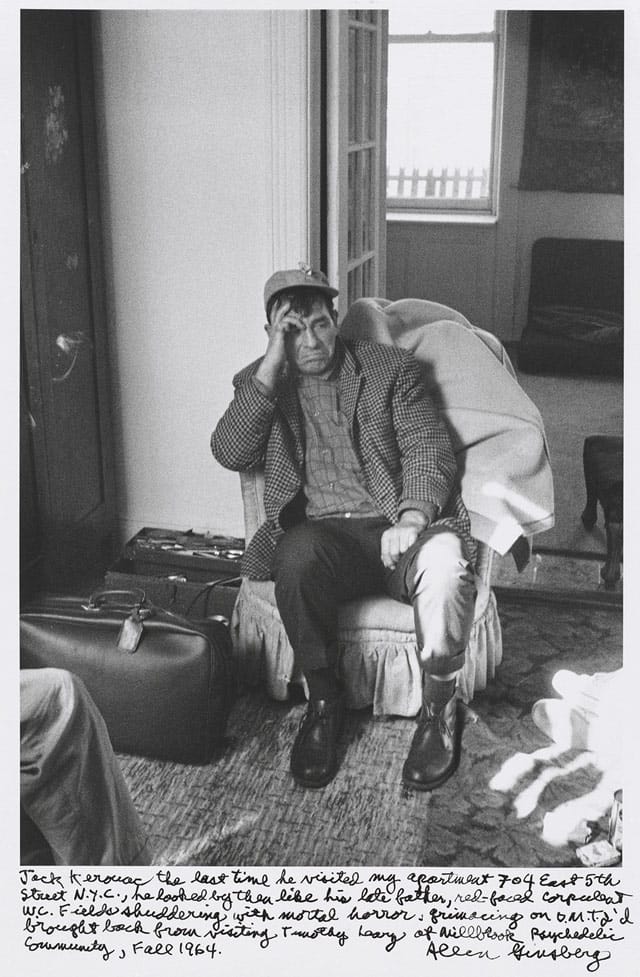

For those of us who cherish the work of the Beats, there’s much to enjoy in this exhibition. William Burroughs turns up often: brooding, sagely, the “invisible man” who crossed the earth a dozen times over in search of obscure psychedelics. Neal Cassady, the real-life Dean Moriarty, stands boastful and broad-shouldered, with the carved hyper-masculine face of a boxer; he is never looking at the camera, and is always in motion. And Jack Kerouac: it’s remarkable how much of his woebegone writing voice is captured in these images. Those expecting to see a new side of the Beats, as I was, will be disappointed. The photographs do not challenge our impression of the subjects as gleaned from Beat literature; they confirm them.

In that sense, it’s difficult to divorce these pictures from what we know about their subjects. Exhibitions of this nature can easily become mawkish affairs; often, we feel nostalgia for a time we’ve never known, some golden chapter never to be replicated. And this is certainly part of the appeal of the show.

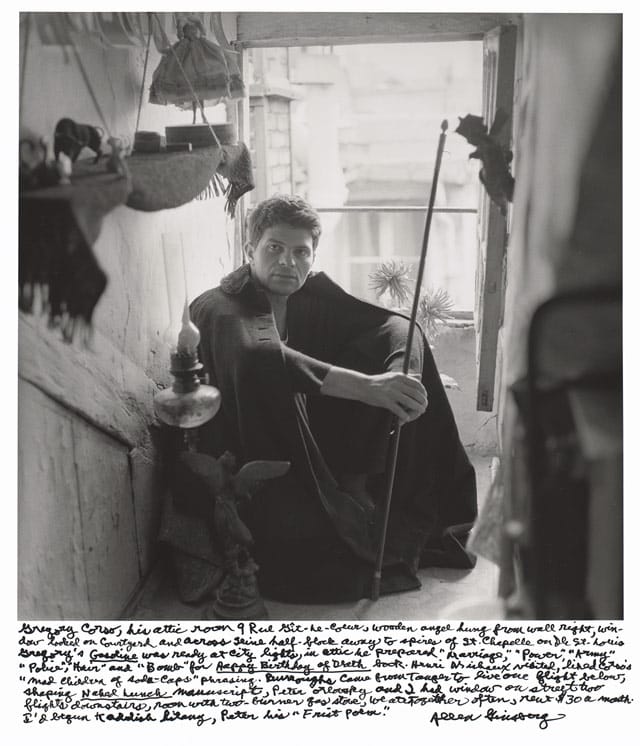

But there’s more here than historical documentation. Some of the photographs stand on their aesthetic merits. We see the poet Gregory Corso, seated on the floor of a tiny attic apartment, draped in a wool coat, clutching a curtain rod that looks like a miniature spear. His posture is defensive, and he looks like a hermit, the spear all he has to protect him from the world outside the window. In another shot, a hirsute and wild-eyed Ginsberg stands nude on a rocky beach, holding a real ten-foot-long spear, with the Sea of Japan behind him. He’d just left India and has the patina of a religious ecstatic, as if he’d tapped into a more primitive faith. Both pictures suggest a retreat from the man-made world, but in different way: the picture of Corso suggests the retreat of fear; the one of Ginsberg, an embrace of the natural world.

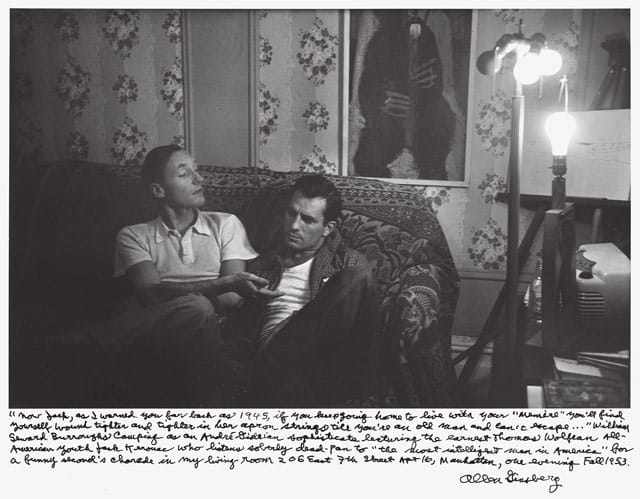

Another delight is a wonderfully intimate picture of Burroughs and Kerouac on a couch in a cluttered New York apartment. They’re lit from the right of the frame by a few naked lightbulbs, and are seated close together, nearly touching. Burroughs, several years the senior, is mid-sentence, gesturing with a hand with a cigarette between his fingers; Kerouac is pensive, listening with great intent. It’s a revealing shot: in it we see not only a time and place, but also a glimpse of the true content of their relationship.

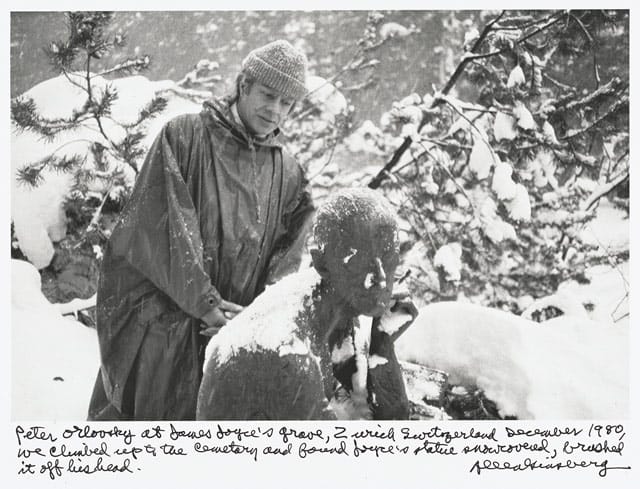

The photographs from the ’50s and ’60s depict ebullient youths on the cusp of fame. Like Ginsberg’s writings, the shots are raw and full of verve. Then, for unknown reasons, there’s a twenty-year gap in the record. We pick up again in the ’80s, and the tone is different. Ginsberg has a more nuanced understanding of form; though he turns up less as a subject, his personality is more present. While the subjects in the earlier photographs are in motion, the majority of the late pictures are quiet and still, with the subject looking into the camera. The pathos is more pronounced: this is a record of who was still standing.

A splendid shot of the poet Peter Orlovsky, in 1980, shows him standing at the gravesite of James Joyce, in Zurich. It’s snowing, and Orlovsky is wearing a baggy parka, peering over the shoulder of a sculpture of Joyce, which is partially out of the frame. The poet looks timid, afraid to interrupt the genius who helped create the literary tradition of which he was now part.

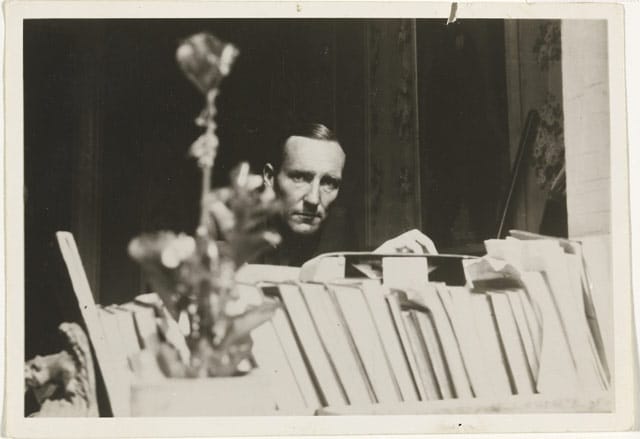

We see Lucien Carr, the man who introduced Ginsberg to Kerouac, sitting at a table, leaning forward on his elbow. He looks straight into the camera. His sleeves are rolled up, his tie loose. Strewn across the tabletop are magazines and a newspaper, empty cigarette packs, two candles to his left. He had once been convicted of murder, for which he did time; now Carr is a working man, an editor. There are pride and dignity in his face, and a trace of wryness in his eyes.

My favorite photograph in the exhibition is of Harry Smith, the eccentric archivist who compiled the American Anthology of Folk Music. He, too, is seated a table, which is littered with empty Chinese takeout boxes, dirty plates, Styrofoam cups, and soy sauce packets. He looks impossibly old and exhausted; Ginsberg’s notes indicate it is 3 am. Smith’s forehead is in his hand, his elbow on the table, and without the pillar of his brittle arm, he looks like he would collapse.

Unlike the ’60s shots, there’s no joy here. Where once was drug- and religion-induced ecstasy, we now see quiet resilience. The storm has passed, and Orlovsky, Carr, and Smith have all made it in their respective fields, you could say. But each picture suggests something lost along the way. Whether they’re peering over the shoulder of a lost literary giant, or continuing to live after taking another’s life, or sitting exhausted in a graveyard of take-out containers, the years have taken a toll on these men.

The last section of the exhibition features Ginsberg’s photos of several of his celebrity friends. The shift is jarring. Madonna and Warren Beatty seem strange company for the writer, who, although he was a celebrity in his own right, we don’t often associate with mainstream icons. Ginsberg was known and revered for operating at the fringes of acceptability; to be chatting with the paragon of pop music seems incongruous.

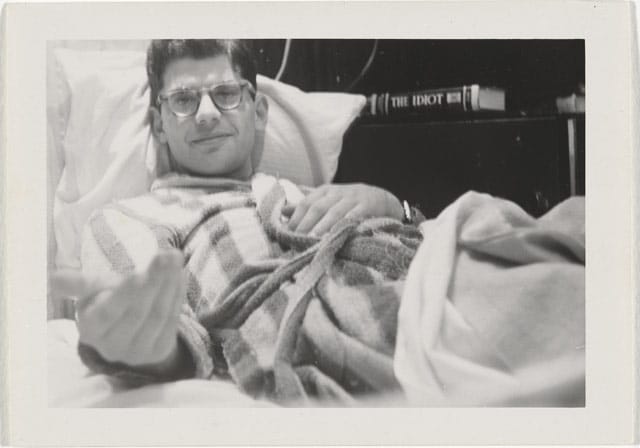

These photos notwithstanding, the pictures from the ’80s and ’90s greatly enhance the emotional power of the exhibition. If it had only featured the shots from the ’50s and ’60s, we would be forgiven for thinking that everyone remains young and beautiful, that no one went bald or died. It would be hollow, telling us nothing of the reality of fame. The twenty years that separate the two sections are an eternity; no longer hungry for recognition or drunk on newfound acclaim, the Ginsberg of the ’80s has grown accustomed to being a beloved genius. But how many peers had been lost to the pressures and temptations of fame? Our last shot of Kerouac, from 1964, is harrowing; we see what that success did to him. Ginsberg, on the other hand, managed to endure, growing into his celebrity. This temporal quality, the evolution of a man, makes the exhibition greater than the sum of its parts.

The last image is a self-portrait, from 1996. Ginsberg is impeccably dressed in a suit and tie, scarf and hat. He’s 69 years old and a few months from his death, yet he looks defiant, strong. While so many of his contemporaries had fallen along the way, he had not. It’s a fitting, dignified end to an exhibition that celebrates a freewheeling life.

Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg continues at the Grey Art Gallery (100 Washington Square East, Greenwich Village, Manhattan) through April 6.