The Evolution of Domestic Architecture Across 100 British Homes

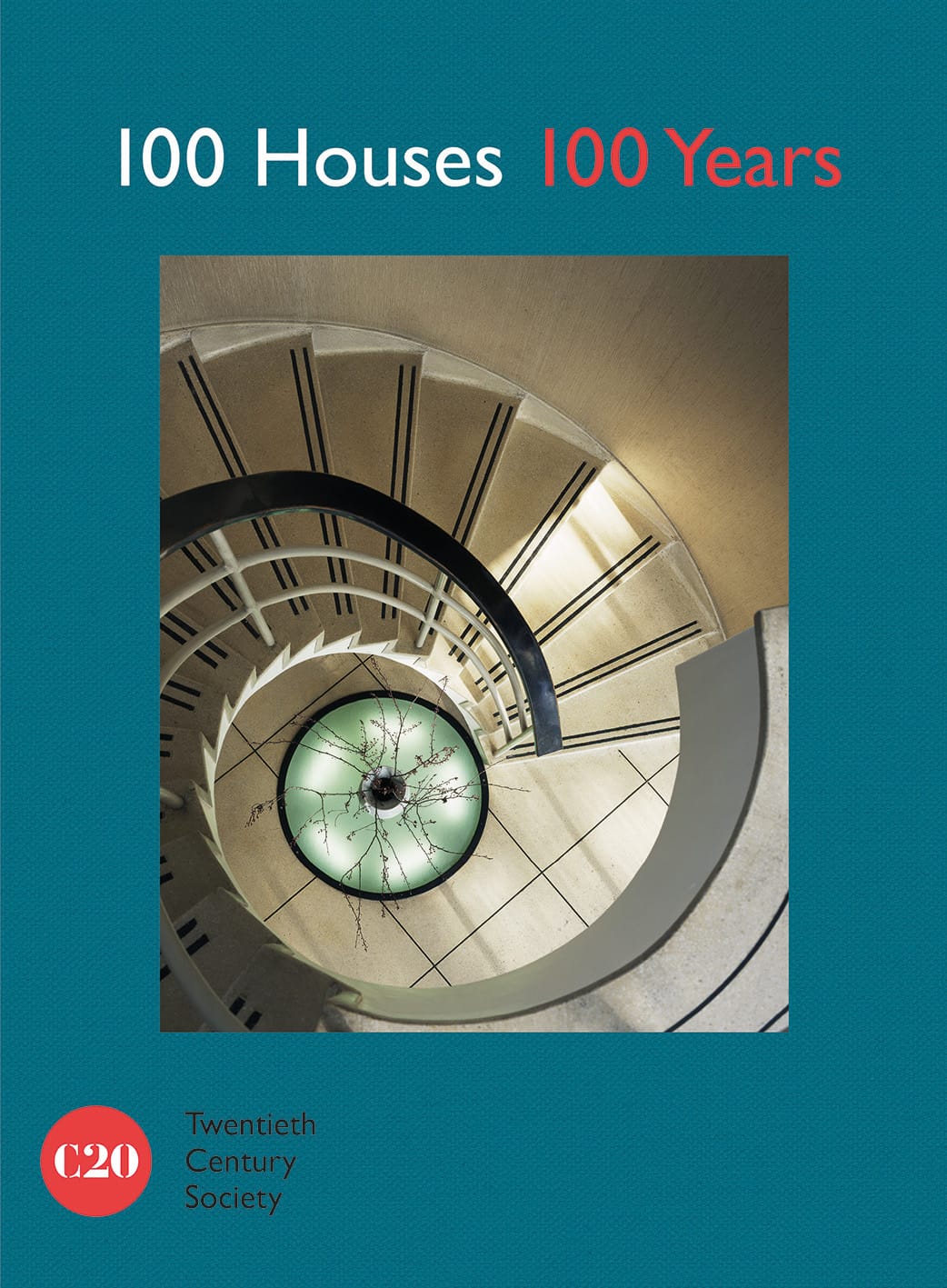

100 Houses 100 Years chronicles a century of architecture through the British home, from classical throwbacks to postwar housing to futuristic designs.

100 Houses 100 Years chronicles a century of architecture through the homes of Great Britain, from classical throwbacks to postwar housing to futuristic visions. The book from the Twentieth Century Society, out now from Batsford, was edited by Susannah Charlton and Elain Harwood. Photographs and short descriptions from critics and design historians accompany each structure.

The book begins with the 1914 Chestnut Grove in New Earswick, featuring Garden Village-style brick homes with a compact layout, built specifically for employees at the Rowntree confectionery company. It continues all the way up to 2015, with the much more lavish House for Essex by Charles Holland and Grayson Perry, a telescoping metal roof crowning its jewel box of ceramic decoration and exuberant color. The scope of the book is narrow, yet it takes in a lot of issues that recent housing has faced throughout the world, including how to construct homes in an economically tumultuous decade, and how to make those choices sustainable. Indeed, not all of the 100 houses have survived.

“Despite this popularity, the futures of even the best twentieth-century houses are not necessarily secure,” writes Catherine Croft, director of the Twentieth Century Society, in the book. For instance, 129 Grosvenor Road in London, designed by Sir Giles and Adrian Gilbert Scott, had a modern take on Greco-Roman architecture inspired by Pompeii. It was later demolished, although it had troubles early on, with bargemen on the Thames stealing pillows from its atrium overlooking the river.

Each year gets one building to express that moment in domestic design, including innovations like William Lescaze’s 1932 High Cross House in Devon, one of the first manifestations of International Style in the UK, and Walter Gropius’s 1937 Wood House in Shipbourne, made after the architect had fled Germany for England, bringing his Bauhaus style to the country home. And there are plenty of innovative oddities, such as the 2003 “Black Rubber House” by Simon Conder Associates, a 1930s fishing hut clad in the waterproof material that makes it both forbidding and cozy, and the home Arthur Quarmby designed for himself in Holme. Built into the earth around an indoor swimming pool, it has its own thermally efficient interior climate. While these examples are often out of reach of everyday homeowners, each year’s house represents a progression in ideas for designing a space to live.

100 Houses 100 Years is out now from Batsford.