World's Smallest Biennale Drops Anchor on Caribbean Islet

There may not be another edition of the new Biennale de La Biche, as the wooden shack that hosts it may well disappear between now and 2019 due to rising sea levels.

What describes itself as the world’s smallest contemporary art biennale is currently taking place on a tiny island off the northern coast of Guadeloupe. La Biennale de La Biche, which launched its inaugural edition on January 6, boasts no grand pavilions and no champagne-sipping crowds; reachable only by small boats, it is identifiable by a dilapidated tin-roofed shack surrounded by mangroves that rise above clear turquoise waters.

The biennale’s claim to its smallness is defined by its scale, as curators Alex Urso and Maess Anand explained. Ilet La Biche, the biennale’s eponymous venue, technically has no ground above water, although it exists as a landmass on Google Maps. Rising sea levels have submerged the island save for the small wooden shack, which is rotting. Still, its interior is dry enough, serving as a fitting place for a remote and incredibly scenic exhibition. If you were to assign the biennale another superlative, it would likely be “Most Relaxing.”

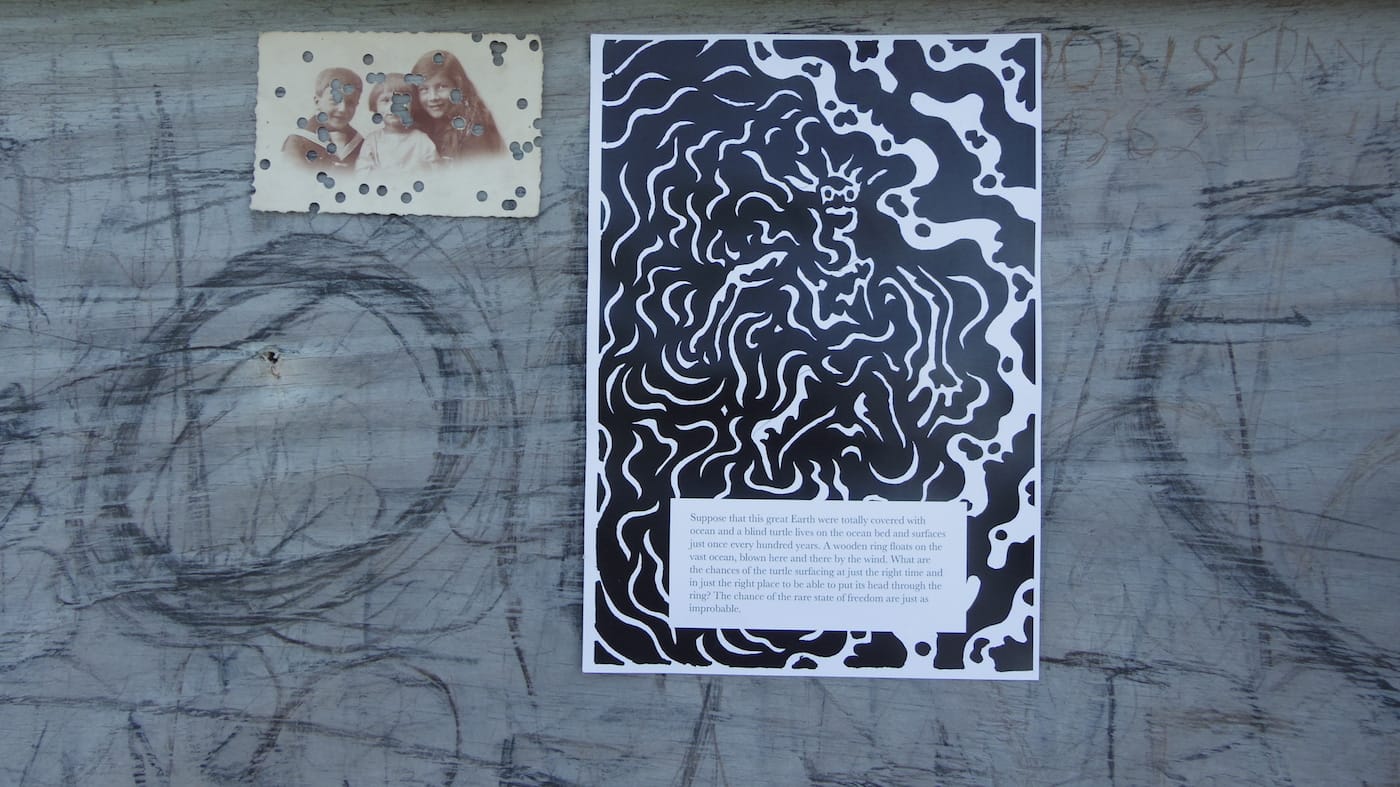

Represented here are 14 international artists, mostly from Poland, where Urso and Anand are based. Invited by the curators to participate, they proposed works based on online pictures in response to “In a land of” — a theme that reflects the island’s particular relationship with its setting; its position of in-betweenness. In the shack, a piece by Zuza Ziółkowska-Hercberg resembles either an unfinished or decaying stained glass window that enlivens the space with color when sunlight hits it; Urso and Icelandic artist Styrmir Orn Guomundsson have contributed paper works to the exterior wall — viewable from a boat or with wet feet — highlighting the structure’s integration with its natural surroundings.

Some artists designed works that overcome these architectural limitations: a sculpture by Norbert Delman floats next to a mangrove and an installation by Yaelle Wisznicki Levi consists of fishing ropes that stretch from the shack far into the shallow waters, disappearing into the blue. Unlike those at a traditional biennale, all of these installations are intended to be left behind, all subject to the forces that are slowly consuming the island itself. Like a traditional biennale, the event does have its missteps, leaving behind a human mark on its landscape — an especially concerning oversight, on this disappearing island.

“The intent of the project was to propose an artistic event overtaking all guidelines that usually characterize the art world today,” Urso told Hyperallergic. “To have artworks on a place visited by a few hundred visitors throughout the year, left without certainties, constricted to consume themselves in loco, and overturn the idea of artworks as monumental and durable fragments in the timeline of art history. We were interested in emphasizing the fragility of these pieces, as elements that decay, following the limits of the world they belong to.”

The uncertainty of the fates of the artworks — and consequently, how they may impact their environment — is perhaps the most interesting aspect of the Bienniale. The event has no end date, and the curators have “no expectations” about a subsequent edition since the island may be completely unfit for a similar display in two years. If they did organize a second Biennale, they envision featuring more local artists and collaborating with Guadeloupean art institutions, perhaps to explore the country’s history and legacy in relation to the slave trade.

The island is not as easily accessible as the many major cities famous for their biennials, but it still receives a fair share of visitors every day. Barefoot and wearing bathing suits, many are tourists who have drifted by while island hopping, having traveled from afar to revel in the French island’s cluster of islets, home to coral reefs, shipwrecks, and wildlife. Urso described the Biennale de La Biche as “an anti-biennale,” but in some ways, it’s still very much like those grand, international affairs, where privilege is your ticket to access.

The 2017 Biennale de La Biche is on view indefinitely on the Îlet de La Biche (Guadeloupe).