Frances Densmore at the Smithsonian Institution in 1916 during a recording session with Blackfoot chief Mountain Chief for the Bureau of American Ethnology (February 9, 1916), the process is similar to that used by Alfred Kroeber in California (via Library of Congress/Wikimedia)

Among the thousands of wax cylinders in the University of California (UC) Berkeley’s Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology are songs and spoken-word recordings in 78 indigenous languages of California. Some of these languages, recorded between 1900 and 1938, no longer have living speakers. The history on the cylinders is difficult to hear. The objects have deteriorated over the decades, mold eating away at their forms, cracks breaking through the sound.

Illustration of a wax cylinder phonograph from The new international encyclopaedia (1905) (via Internet Archive Book Images/Flickr)

A project underway at UC Berkeley is using innovative optical scan technology to transfer and digitally restore these recordings, even from cylinders that are broken. Supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) through a NEH-NSF partnership called “Documenting Endangered Languages,” the initiative aims to preserve about 100 hours of audio. The collaborative restoration project involves linguist Andrew Garrett, digital librarian Erik Mitchell, and anthropologist Ira Jacknis, all at UC Berkeley, and utilizes a non-invasive scanning technique developed by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory physicists Carl Haber and Earl Cornell.

Haber previously utilized 3D mapping to reproduce Alexander Graham Bell’s voice for the recent Hear My Voice at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The indigenous recordings are part of Project IRENE, which has a goal to make digital versions of around 3,000 wax cylinders at the Hearst Museum. Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber began his field audio collecting in 1901, a month after becoming the curator of the then-new museum. Although the recordings are limited, each only a few minutes long, and were captured at a subjective start and stop by Kroeber, they are invaluable for understanding the diverse languages of indigenous life in California.

Andrew Garrett, professor and chair in the UC Berkeley Department of Linguistics, told Hyperallergic that all the cylinders being scanned are accessioned in the California Language Archive. A full description of the cylinder contents is also in a digitized version of Richard Keeling’s guide to the early fielding recordings at the Hearst Museum (then called the Lowie Museum).

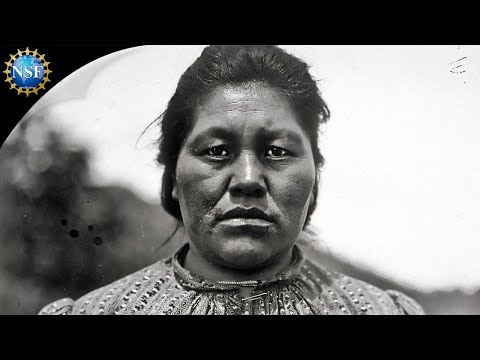

As stated on the Project IRENE site, due to “the culturally sensitive material of the content on these cylinders, and out of respect for the contemporary descendants of many of the performers on the recordings, access to the majority of the audio being digitized is currently restricted.” One of the publicly available recordings is that of Ishi, recognized as the last surviving member of his Yahi tribe, who lived out his final years at Hearst Museum. His voice, among many being recovered from the noise of the wax cylinders, leads the recently-shared video from NSF below.

Read more about Project IRENE online at UC Berkeley.