A Photographer Captures Chilean Street Life, from the Hustlers to the Homeless

In a retrospective in the south of France, Paz Errázuriz's kaleidoscopic vision encompasses all aspects of life in Santiago.

ARLES, France — With more than 25 exhibitions, the 48th edition of Les Rencontres de la Photographie d’Arles in France is a visual feast. One of the welcome highlights this year is a nod to Latin American and women photographers. Numerous shows, from The Specter of Surrealism to Iran, Year 38 highlight women artists. The same goes for retrospectives: For example, Joel Meyerowitz’s Early Works is balanced by a similar show of Annie Leibovitz, The Early Years, 1970–1983: Archive Project # 1.

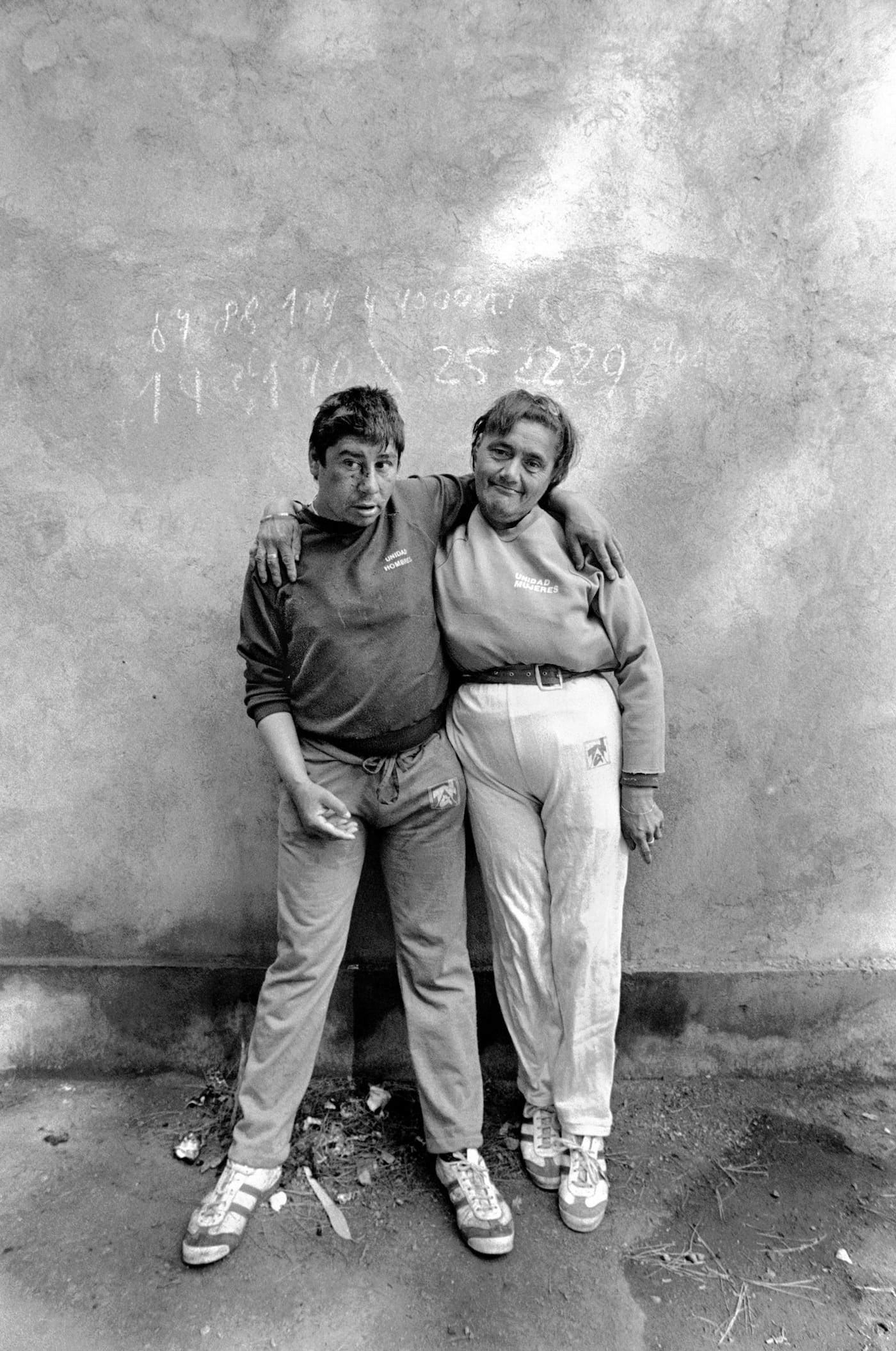

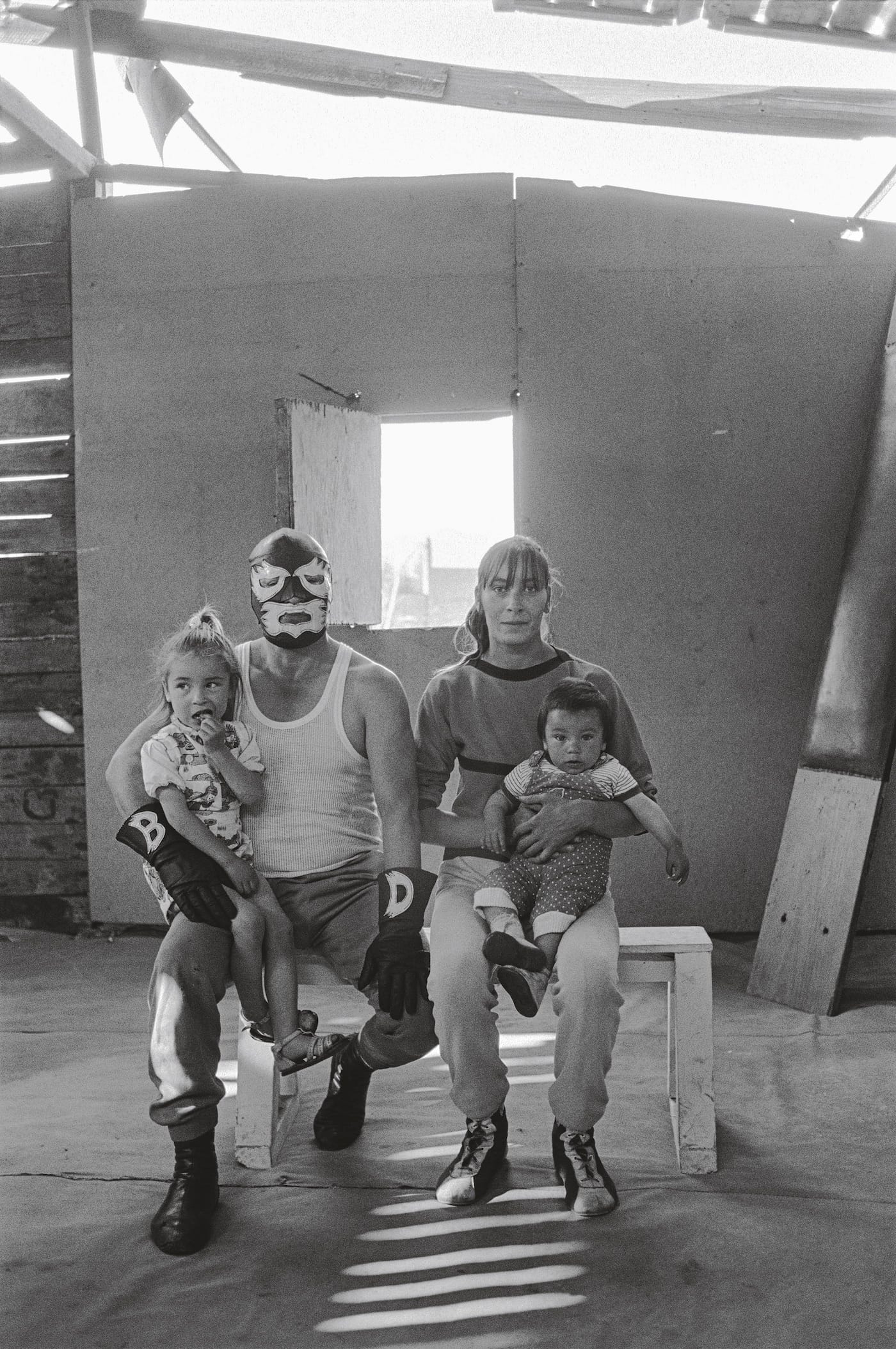

The Photo Madame Figaro prize for a woman photographer, for which there were eight finalists this year, went to distinguished Chilean photographer Paz Errázuriz, who also has a retrospective at Arles, A Poetics of the Human. Errázuriz’s kaleidoscopic vision encompasses all aspects of city life. Firstly, the social: In the 1980s, she focused her camera on her native Santiago, from those in the upper middle class (“Kennel Club, Santiago,” 1988) to lowest, with numerous images of the poor (“Compadres, Santiago,” 1987), the homeless, and the disenfranchised. In the dangerous political climate of the Pinochet dictatorship, Errázuriz documented protests, often putting herself at risk to do so. Thus her output from this period ranges from instantaneous street photography to intimate composed portraits. The show’s curator, Juan Vicente Aliaga, commented via email: “The images of transvestite hustlers, prostitutes or natives from the Kawesqar community are the outcome of the long time Errazuriz spent in the company of people who often became her friends.”

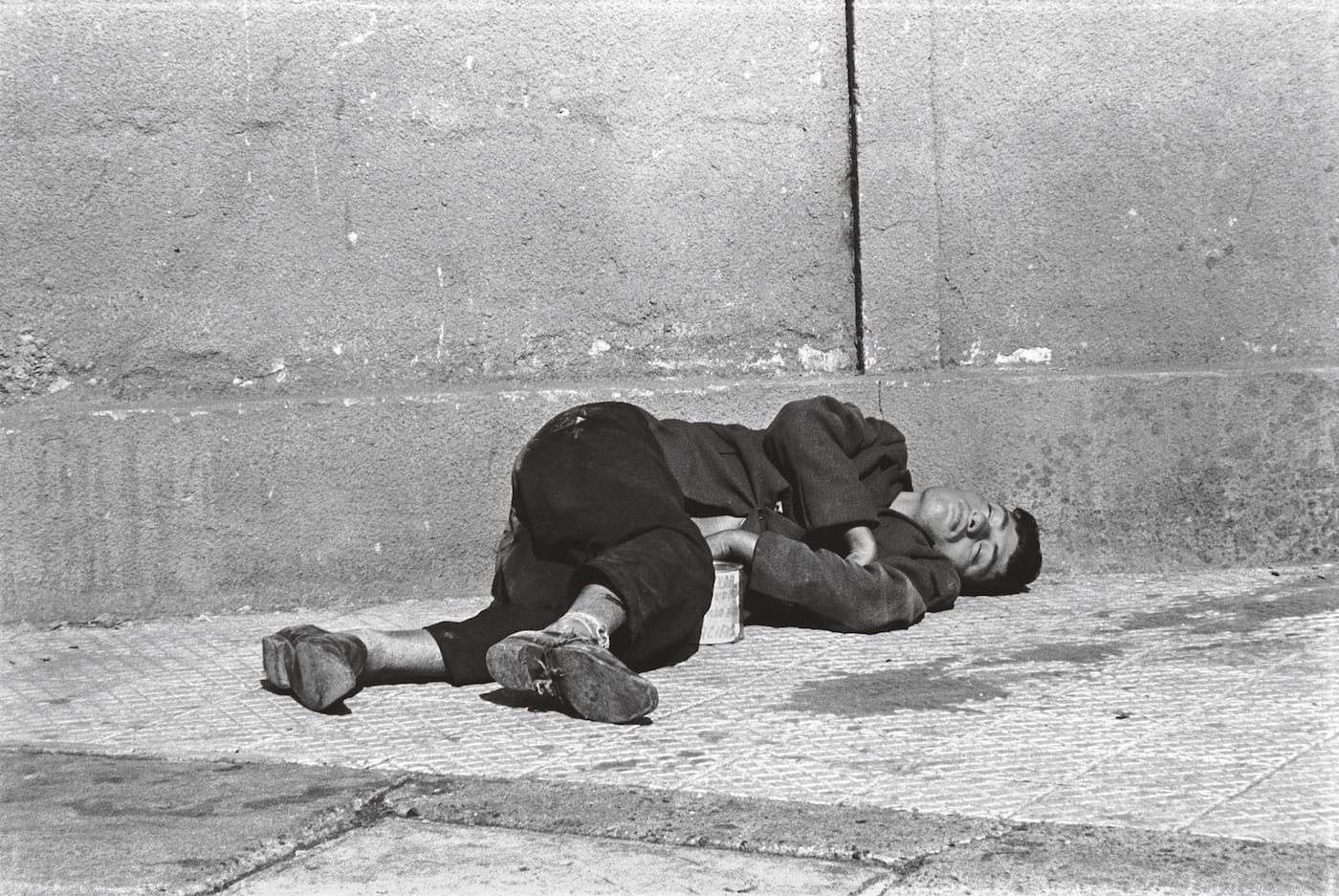

In a sense, the first two decades of Errázuriz’s career run in parallel with much of Latin American photography, which is beautifully displayed in Urban Impulses: Latin American Photography, 1960–2016, with photographs from the private collection of Leticia and Stanislaw Poniatowski. There is a clear emphasis on urbanity, on the poor and marginalized, and on political strife. In the section “Shouts,” we see Mexican Hector Garcia’s images of student protests (“Marcha estudantil,” 1968) and Argentine Juan Carlos Romero’s diptych, “La memoria y el olvdio” (1989), that, like many others, is haunted by the desaparecidos (“the disappeared”). Meanwhile, another section, “The Damned,” features Miguel Rio Branco’s iconic diptych, “Dog Man / Man Dog” (1979). That image, in which both animal and human are shown lying on the sidewalk, seen from a high angle and blending in with the muted colors of dirt, succinctly captures a mix of abjection and societal indifference. But Aliaga also stresses that he sees Latin American artists as having vastly varied approaches, and he believes that Errázuriz stands apart from those photographers who “portray Latin American art as equating passion with violence [or who employ] baroque or garish aesthetics.”

While Errázuriz’s topics range from sociopolitical to ethnographic — with a section devoted to the mestizo population — nothing quite prepares us for the shock at the exhibition’s end (although we may argue that Errázuriz’s progression, from documenting poverty to capturing those who are perhaps most severely ostracized, the mentally ill, is a natural one). In the poignantly titled “Heart Attack of the Soul” series (1994), the artist documents couplets in which patients at the psychiatric hospital Philippe Pinel de Putaendo are paired up with their loved ones. Mental illness is a thorny subject, one that can make images seem distanced or abstract. Yet Errázuriz’s photographs radiate warmth. In one photo in this series, “Heart Attack 26, Putaendo” (1994), mother and son pose playfully for a portrait, their gaze meeting ours, as they stand side by side, touching at the hip. The same duo is captured in another image as one lights a cigarette off the other’s. Perhaps the most expressive image is of a boy looking away from the camera with an open grin, in the midst of saying something, as an older man hugging him looks directly into the lens, his hand on the boy’s shoulder. In the image’s composition, there is a sense of movement and vigor, and a keen desire to communicate.

If the images in “Heart Attack of the Soul” are tender and bittersweet, the final series, “Antechamber of a Nude” (1999), which was produced upon a return to the same institution and is devoted exclusively to the women in it, is much fiercer and more uncompromising. It starts off with a beautiful frontal nude — the woman looks straight at us, her walking stance powerful and confident. But beyond that, we encounter vulnerability, abandonment, perhaps even rage. The women, old and young but mostly worn and ravaged by age and illness, are captured in intimate moments, often in a bathhouse. Vulnerable and naked, at times they look straight at the camera. In those instances, there is a jolt of incomprehension in their eyes, and, on our part, a lurking feeling of invasion. This is strengthened by the stark contrasts, the deep shadows, and the metal grate that Errázuriz captures, all of which contribute to the claustrophobic, oppressive sense of confinement, but also of privacy, even secrecy. Repeatedly we see the women shield their breasts, for protection or out of deep emotion.

There is in these images, in their startling poses and crude takes, something of German expressionism, of George Grosz, perhaps even Goya’s uncompromising visions of decay and Da Vinci’s grotesques. Which is not to say that Errázuriz treats her subjects cruelly or observes them with a cold or objectifying glance. Rather, she seems to have arrived at photography’s, or at portraiture’s, limits. Yet she still gives her painful testimony. She does not look away.

A Poetics of the Human is on view at Atelier de la Mécanique, Arles, France, through September 24.