Kara Walker's Show is a Painful, Necessary Reminder That US Culture Wars Never Ended

Walker's drawn and collaged images depicting haunting scenes of abuse and violence refuse to let us look away from America's bloody past and present.

Atop Kara Walker’s large-scale drawing “The Pool Party of Sardanapalus (after Delacroix, Kienholz)” (2017), currently on view at Sikkema Jenkins, a mammy reclines; below, a group of young girls pull the entrails from a white man held down on the ground. Nearby, a hooded black male wields a shank against another black man, and a white man in a corset stabs a black male in the chest. On the outskirts of the composition, other characters are either oblivious, witnessing these acts, or simply turning away. Here, Walker adapts Delacroix’s 1827 painting, fixating on his depiction of the Assyrian king’s indifference to human life. Not dissimilar to Sardanapalus’s uncaring disposition, the work alludes to a 2015 incident in McKinney, Texas, where a white police officer, responding to a disturbance call about a neighborhood pool party, body slammed a young black girl in her bathing suit, and pulled a gun on two young boys who came to her defense. The cop, Eric Casebolt, not only used excessive force, his actions highlighted the denial of innocence to black children, who are criminalized early and often because of the color of their skin. Walker’s twisted, draconian pictures are a cypher for the present moment inasmuch as they skeptically obscure the possibility of alternative futures for our nation.

I approached Walker’s new show of figures sketched and collaged onto paper and linen with somber eyes and a growing impatience for spectacle. A prominent critic posted on Instagram that they felt “uncomfortable” being in the room, perhaps a desired effect of the artist. I shared their discomfort, though not because of a squeamishness brought on by white guilt, but because, quite frankly, like Walker, I’m vexed. I’m incensed. I’m fatigued. At times I’m almost too weary to look on. These feelings are all too familiar. Mere weeks after violent white supremacist neo-Nazis stormed Charlottesville, our president took a momentary reprieve from publicly shaming black American athletes for their peaceful protests of racism, inequality, and police brutality to throw paper towels at Puerto Rican citizens fighting for their survival after a catastrophic hurricane. Just days ago, a white American terrorist with easy access to automatic weapons slaughtered 59 people and injured hundreds more at a country music concert in Las Vegas. Feeling or acknowledging momentary discomfort is not a substitute for doing the work of dismantling structures, attitudes, and mindsets that perpetuate racism and inequality. Minutes into seeing the show, I quickly realize my energies are better reserved in outrage for our country’s never-ending political quagmire. Walker is still the art world’s proverbial soothsayer, rabble-rouser, and provocatrice; her artworks are surprisingly less shocking than our national news cycles. And if her machinations, as some critics suggest, leech onto black pain, they also reveal the psychodramas of our current reality. As Jennifer Baker eloquently wrote for Electric Literature: “We need to better understand that the Black body is not simply a conduit that receives violence but also one that exudes beauty and complexity.” Walker obviously begs to differ. She continues to dirty her hands in the mud of US racial mythology, a job not for the faint of heart. I’ve reconciled Baker’s sentiment with my own desire to see more art that engages with black vitality, resilience, and perseverance. But yet and still, we must not look away.

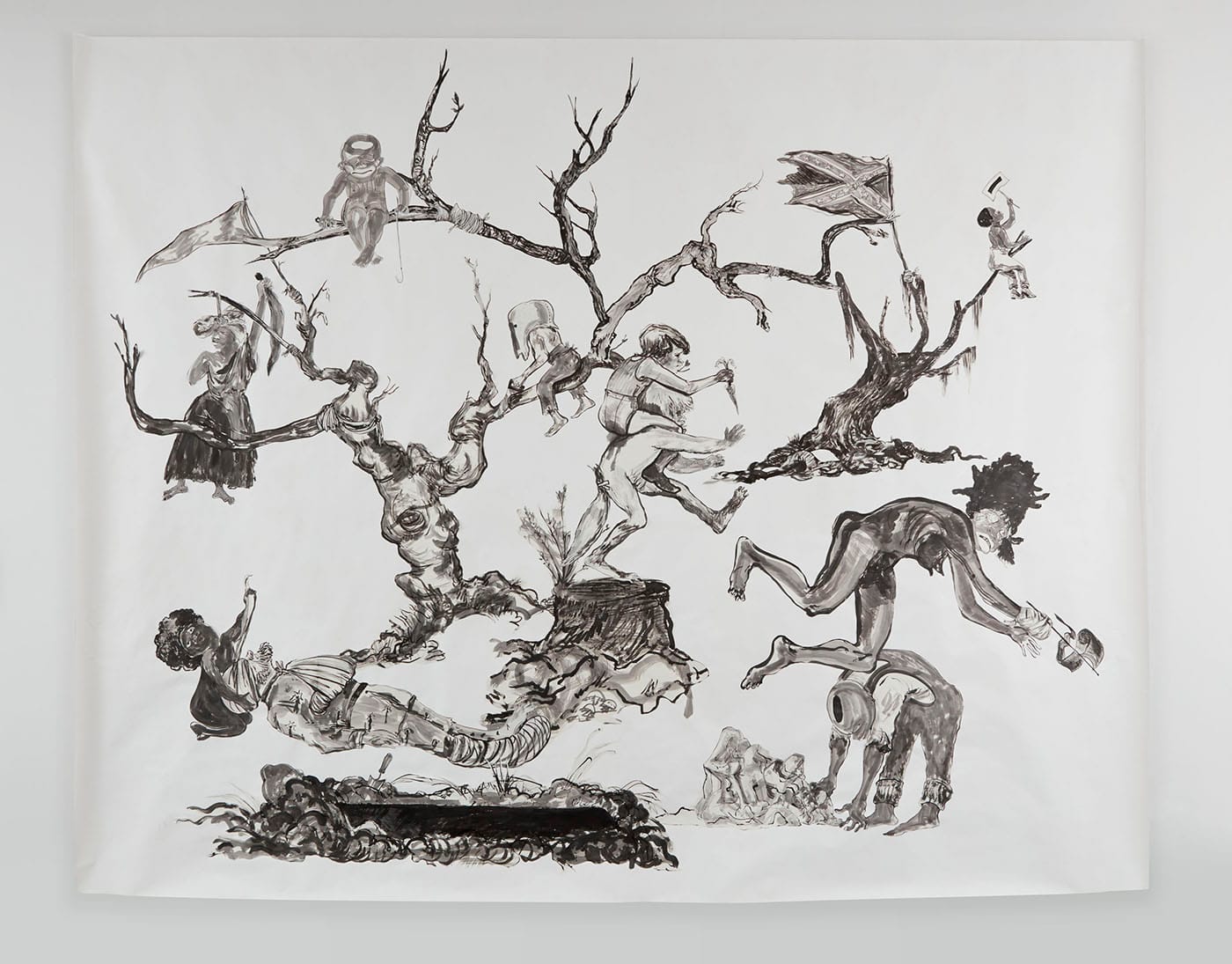

In the painting “The (Private) Memorial Garden of Grandison Harris” (2017) Walker depicts Harris, an enslaved man who, in the 19th century, was forced to rob graves to supply medical students from Georgia College with cadavers, dragging a lifeless nude black woman away from a dark hole in the foreground. Adjacent to the figure of Harris, Walker collages a scene reminiscent of the “Fearless Girl” of Wall Street, here seated behind the reigns of a toy bull and beneath what appears to be a silhouetted rendition of one of the Confederate obelisks that still populate the American South — or even a 19th-century medical syringe. Raging debates about public monuments bring to mind recent protests against South Carolina doctor J. Marion Sims, memorialized in Central Park. Sims performed medical experiments on un-anaesthetized enslaved black women. Walker’s antebellum phantasmagoria of Lady Libertines, politicians, grave robbers, carpet baggers, bullet-riddled soldiers, Confederate flags, tar babies, Bre’er rabbits, and police officers equipped with riot gear are all complicit and bound within a vast ecosystem that feeds on sexualized trauma, unbridled violence, and a spreading malaise of apathy. How are we to wrangle such entanglements between victims and victimizers, witnesses and perpetrators, debauched pleasure and overwhelming disgust?

Ironically, most of the works in Walker’s show will go to museums that will proudly collect them, while for the sake of political neutrality many will likely remain timid when the time comes to roll up their sleeves and speak truth to power. As difficult and divisive as her images are, they point to a reckoning that we can no longer afford to ignore. Racism will remain inseparable from America’s history, its present, and its future. It penetrates every crevice and corner of our institutions, and pervades every fiber of our collective being. Walker’s work does not signal an impending culture war; it is a reminder that the previous ones never ended.

Sikkema Jenkins and Co. is Compelled to present The most Astounding and Important Painting show of the fall Art Show viewing season! continues at Sikkema Jenkins (530 West 22nd Street, New York) through October 14.