25 Years of Photographing the Human Skull

Lynn Stern's 25 years of skull photographs are compiled in a new book, which considers the art historical context of this vision of death.

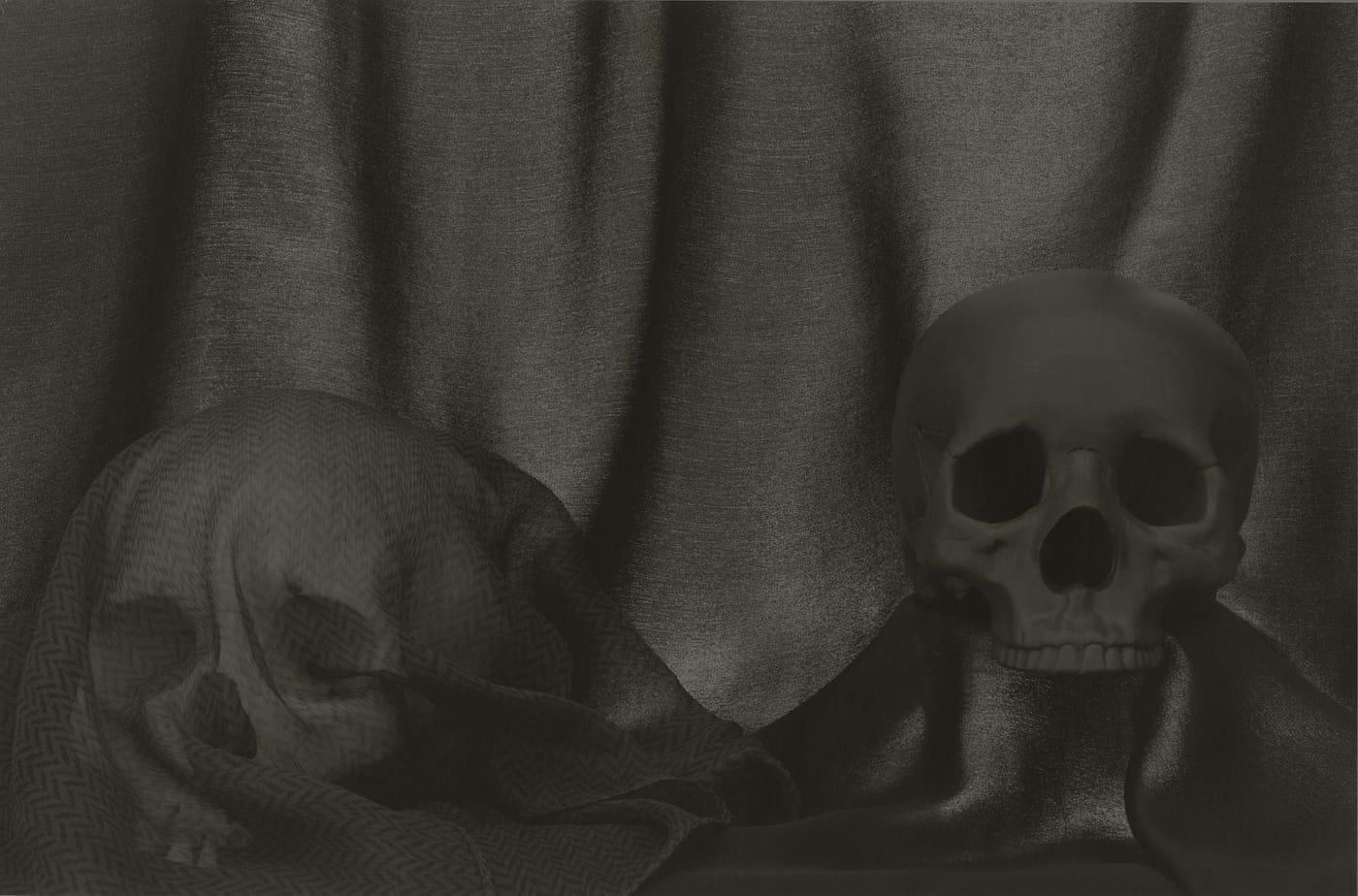

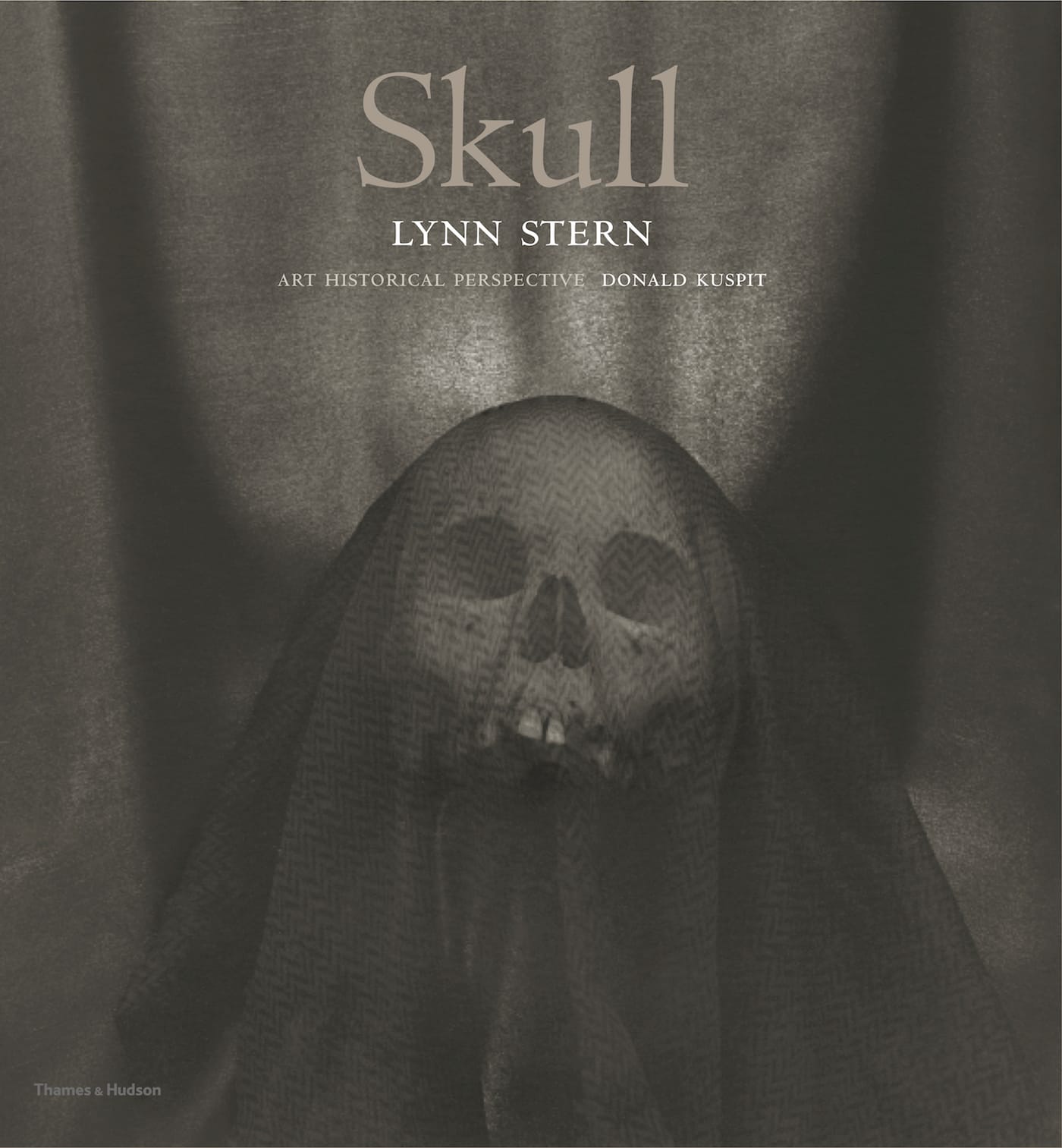

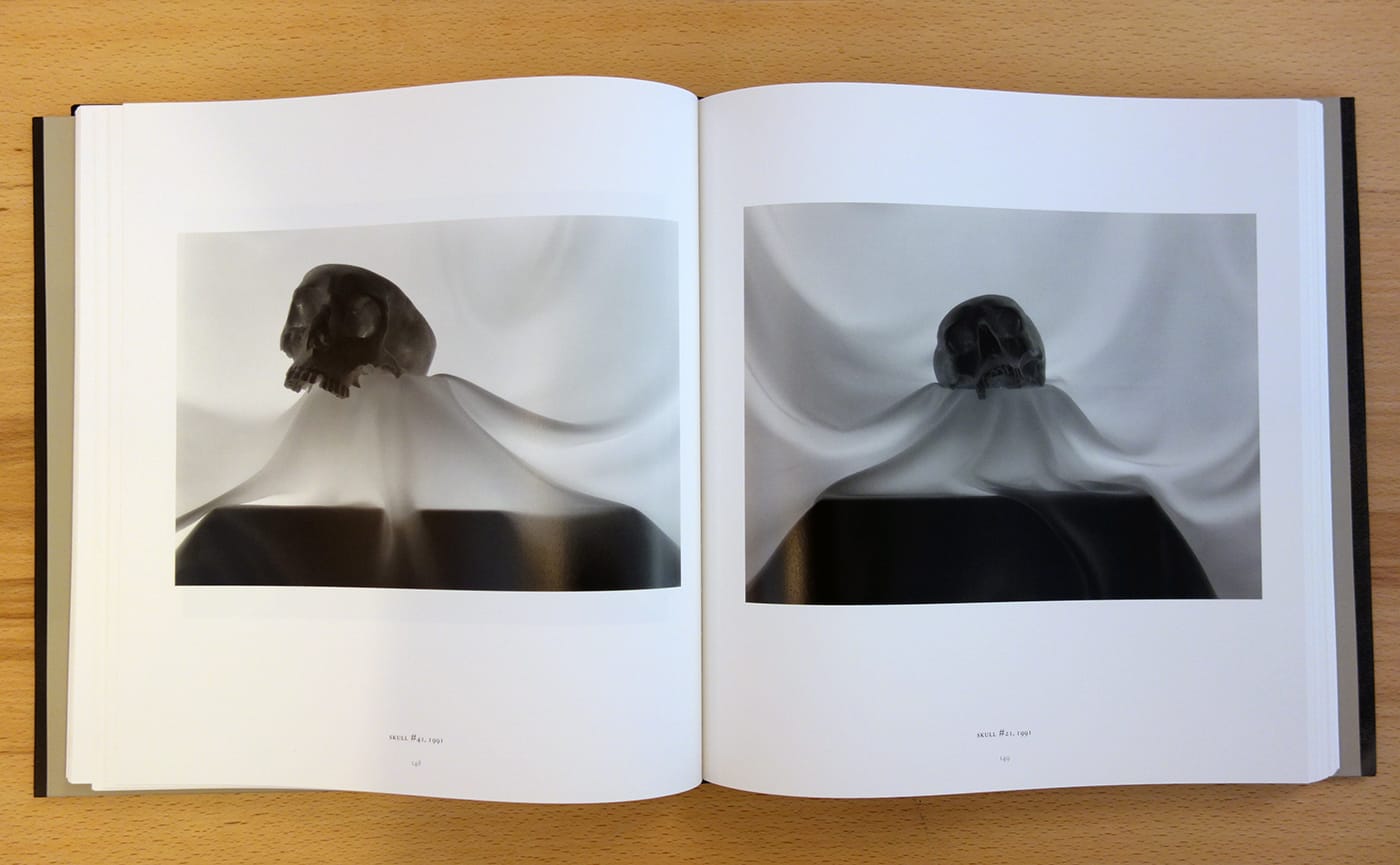

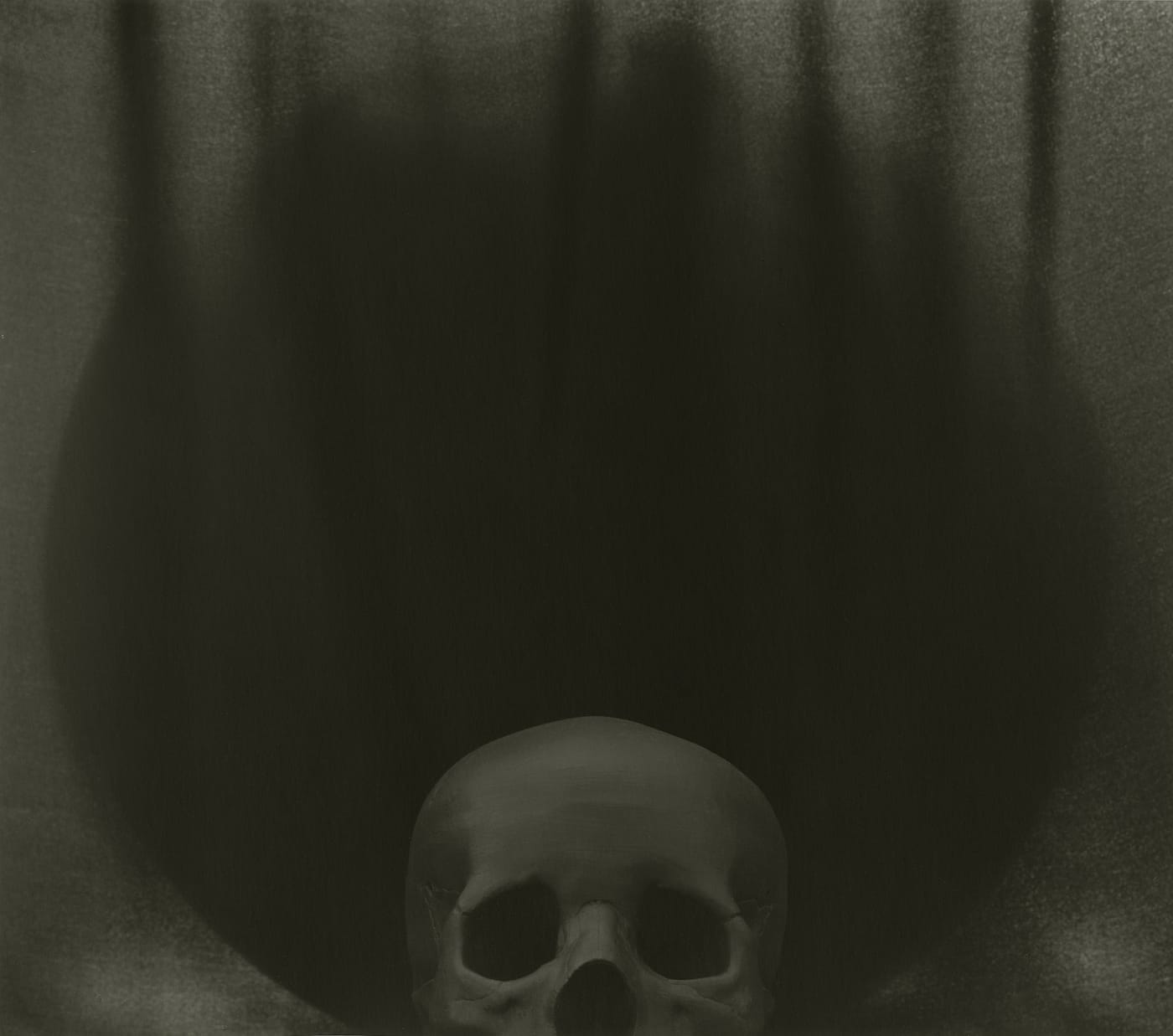

Lynn Stern has photographed skulls for 25 years, capturing them backlit like architectural forms and abstracted behind scrims. Skull, a new book from Thames & Hudson, features almost 150 photographs from eight of Stern’s series on this vision of mortality.

“I have always been terrified of death, and I never thought about using that in my work,” the New York-based artist told Hyperallergic. Stern added that although skulls have become something of a kitschified fashion accessory, many of us still have a standoffish relationship with death. “It’s very much in the culture, but it’s in the culture with a kind of denial,” she said.

Yet around 1989, she was struck by an article by Donald Kuspit, who described how, when a skull appears in a painting, “it knocks everything else out of the picture.” Around the same time, she saw Gerhard Richter’s paintings responding to the Red Army Faction, in which the image of a dead woman was gradually blurred into oblivion.

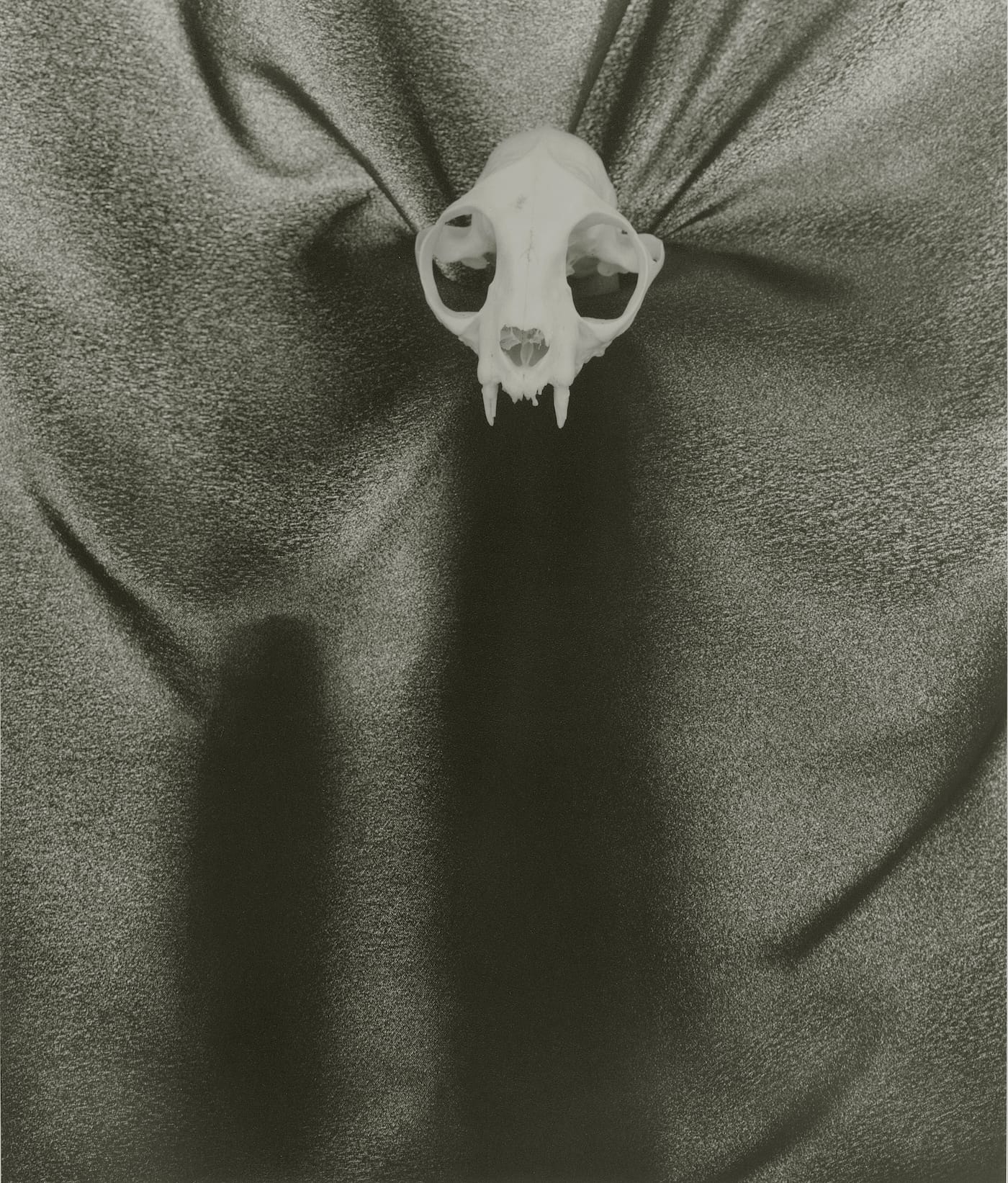

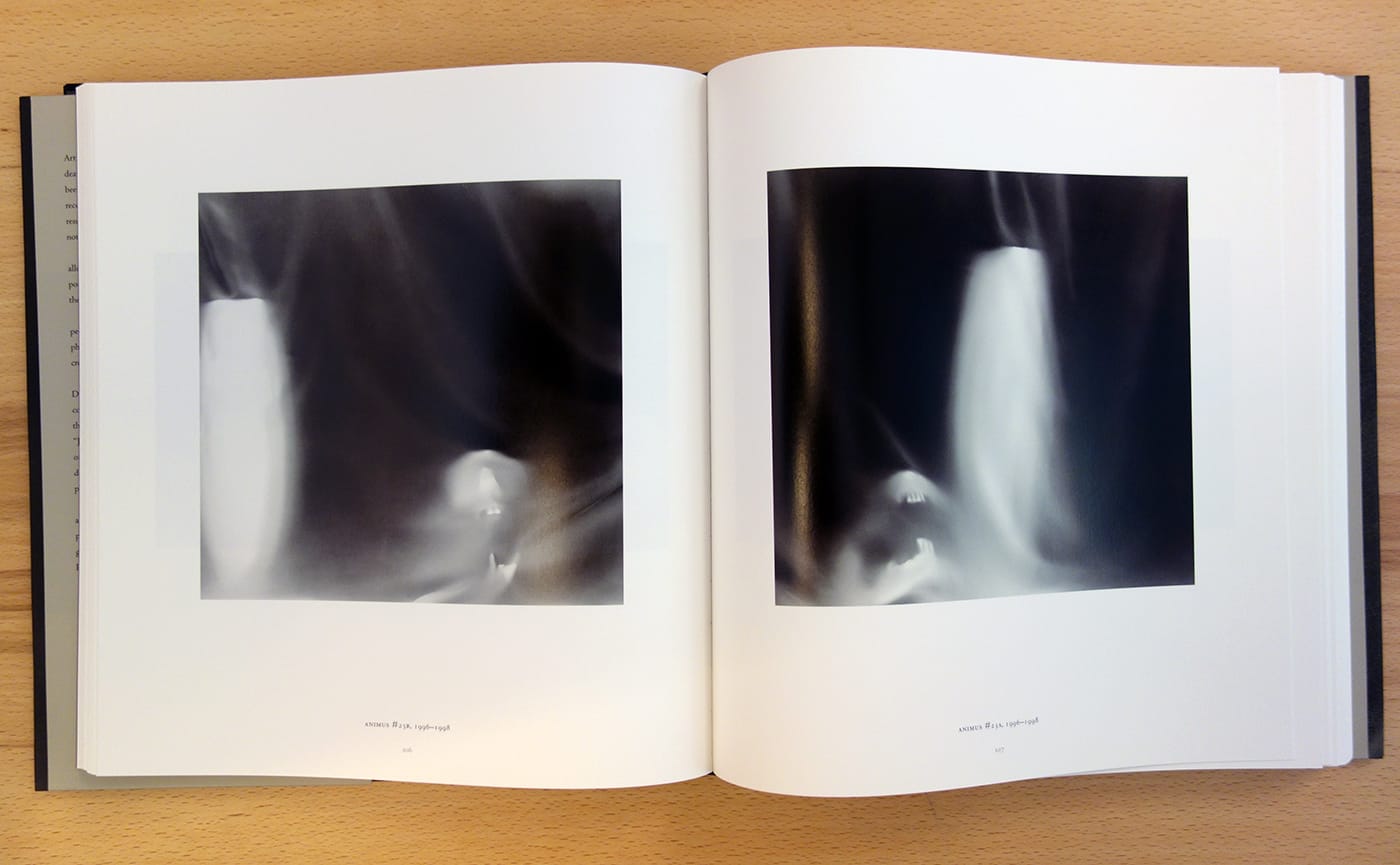

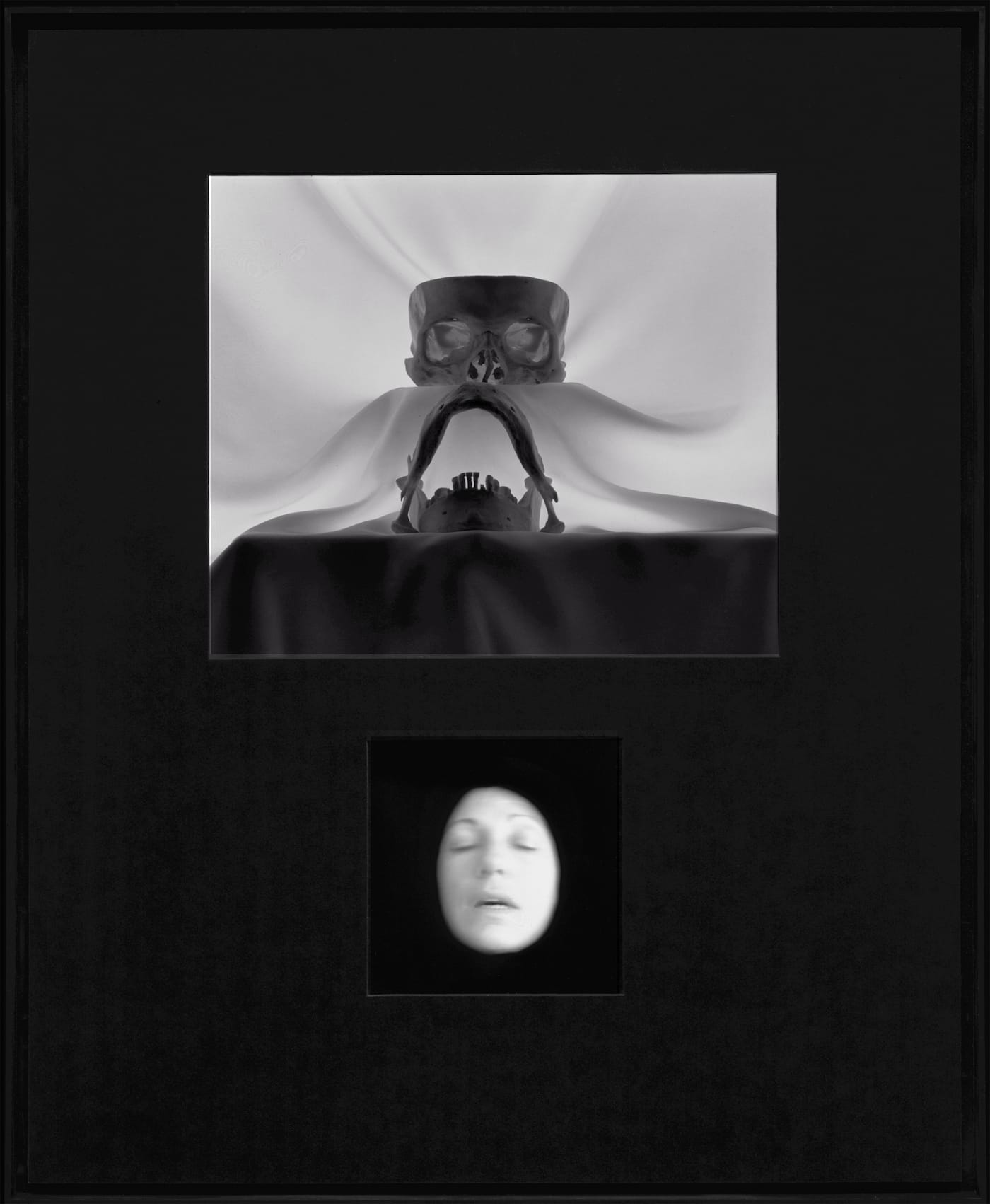

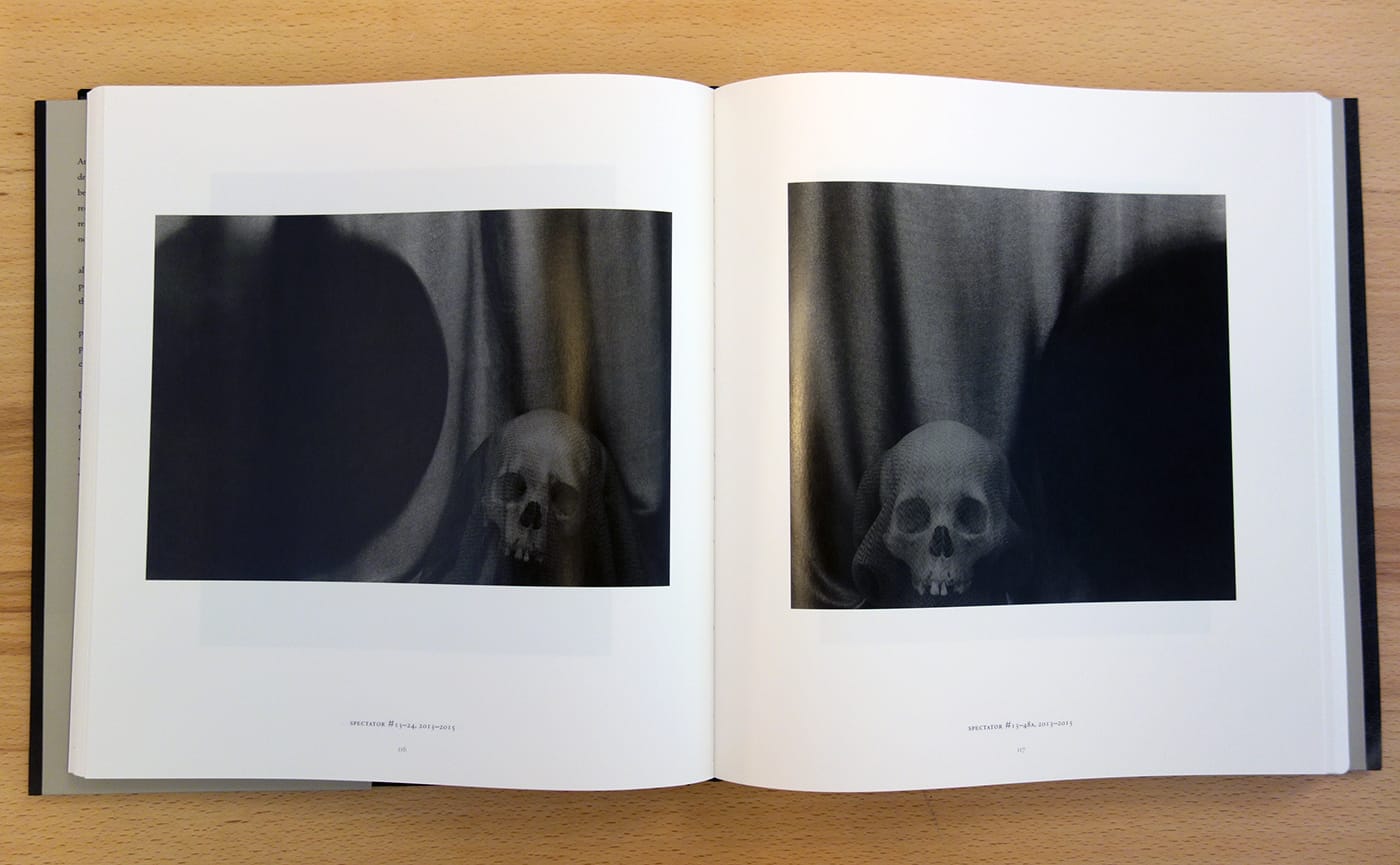

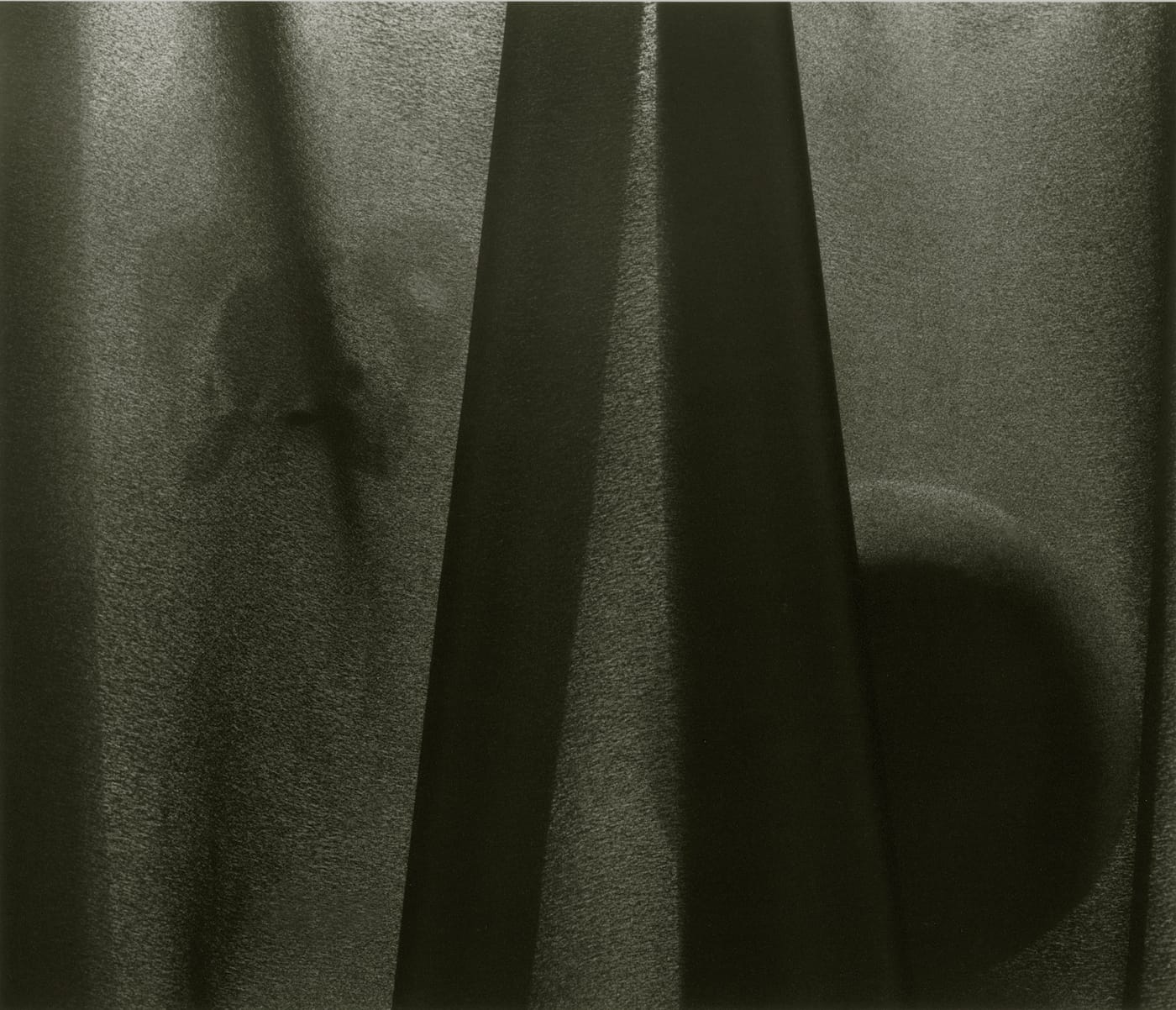

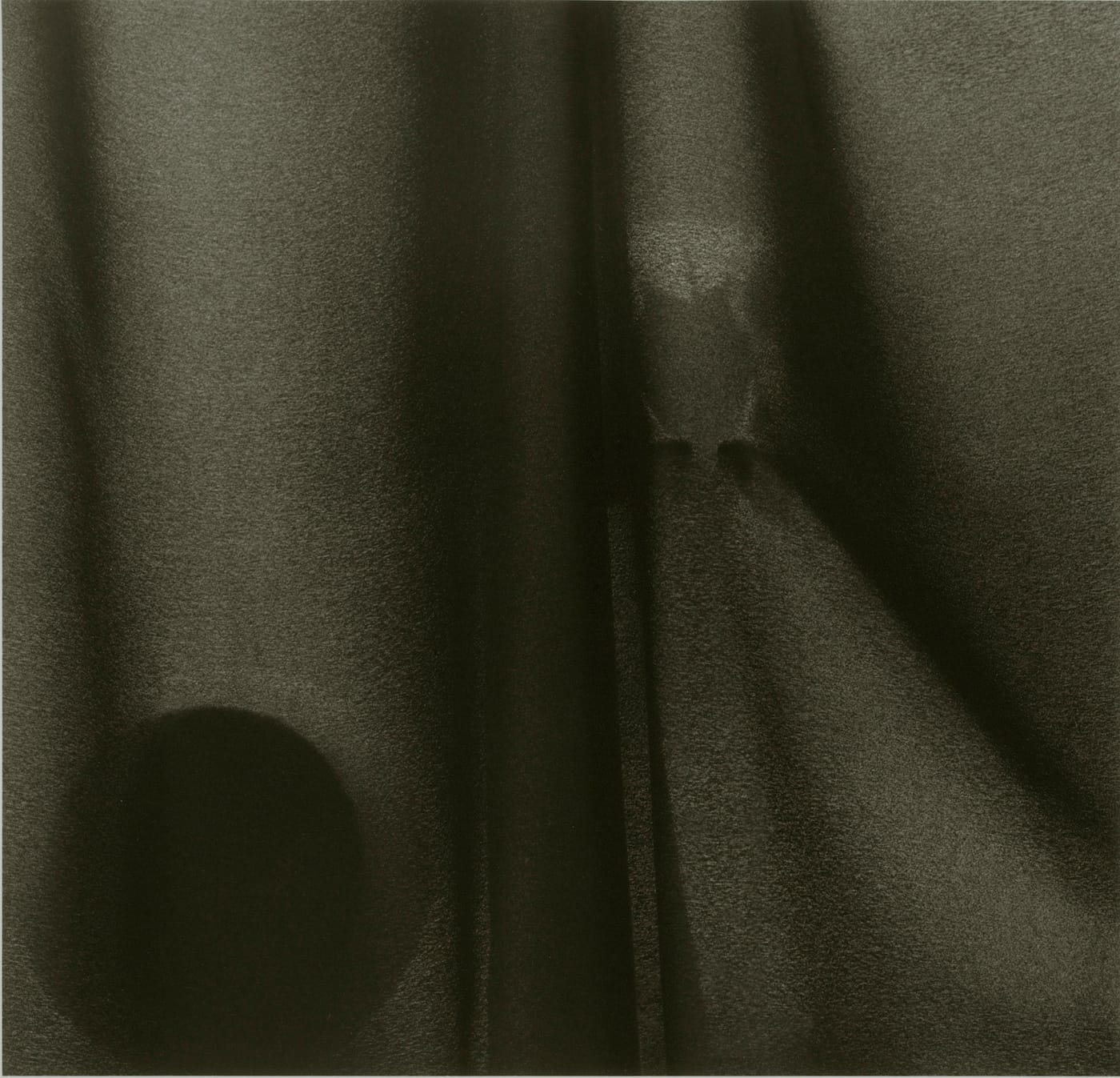

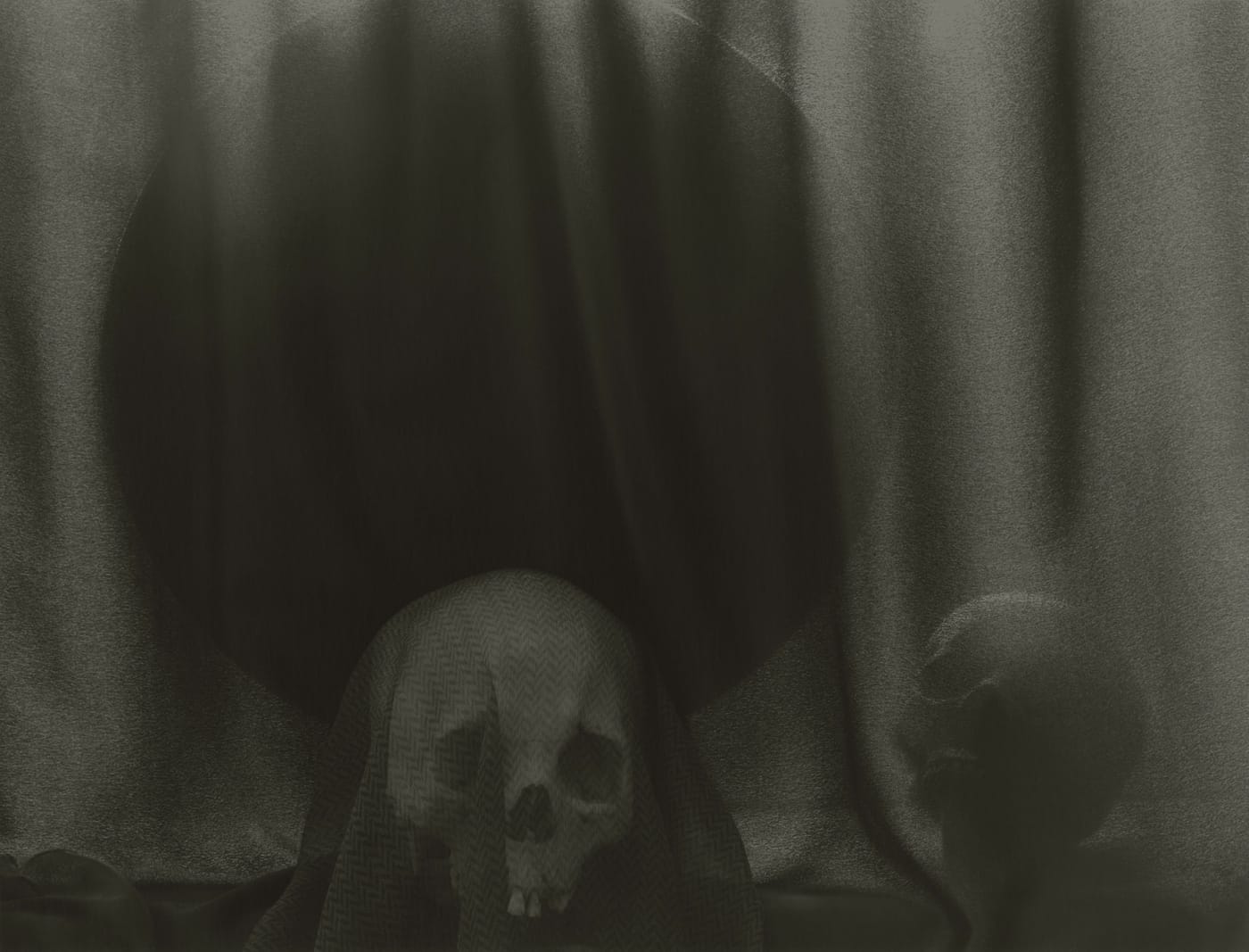

“I got the idea of trying to combine the skull and myself as a death mask,” Stern said. In the first skull series, called Dispossession (1990–92), a black skull in shifting positions, its jaw sometimes divided from the cranium, is contrasted to Stern’s face, which never changes. “On the psychological level it was a kind of exorcism,” she said of her work with the skull, and it was a subject that she kept returning to even as she moved on to different projects. Full Circle (2001–09) had ambiguous black circles mingling with skulls masked by a scrim, symbols of the infinite, while (W)holes (1994–2008) involved animal skulls staged ethereally, with translucent black backdrops, fangs and broad eye sockets projecting a wild form.

“I have tried in all of the work, whether they’re the human skulls or animal skulls, to invest them with a sense of life and energy and movement and emotional qualities,” she explained. “From my point of view, what sets them apart from a lot of other work that photographers have done with skulls is they are not presented in a literal manner.”

An extensive essay by Donald Kuspit accompanies Stern’s photographs in Skull. In it, he considers her use of the skull in the context of work like Irving Penn’s photographs of animal skulls, and Hans Holbein the Younger’s anamorphic skull in “The Ambassadors” (1533). Unlike in other artist’s monographs, which tend to separate essays from the images, his narrative is woven through the entire book, forming a rhythm between the recurring visage of this exposed human core, and his considerations of its ubiquity in art. He notes that in “Stern’s epidemic of death — the isolated, autonomous skull run rampant and unstoppable — suggests that it will never submit to anyone, suggests that it is as all-powerful as Holbein’s death-dealing skull.” He adds that this “omnipotence of death is Stern’s theme, not the omnipotence of the artist.”

Light and shadow are also a major theme in Stern’s work. Although she has mainly employed three skull “models” over the years, all acquired legally from a medical supplier, the use of natural and indirect illumination, and its dynamic lines in the black-and-white photographs, gives them a universal quality. These bones could be anyone’s, and there’s an inevitability embodied by their presence. As Stern said, “In all of the work, what has been uppermost in my mind has been animating them and infusing them with some kind of mystery and light and movement, so they’re not just objects against a backdrop.”

Skull by Lynn Stern is out now from Thames & Hudson.