Treasures of the Master Drawings Fair, from a Surprising Portrait to a Strange Dreamscape

I have developed some affection for the enterprise, which is much more diffuse than other New York fairs.

A few days ago I made my return visit to this year’s iteration of the annual Master Drawings in New York fair. I have developed some affection for the enterprise, which is much more diffuse than other New York fairs — to experience it one needs to perambulate among a selection of Upper East Side galleries beginning from a 54th Street location (technically on the west side) up to 93rd street. (Most, though, are clustered between 60th and 80th streets, so it can be easily walked in an afternoon.)

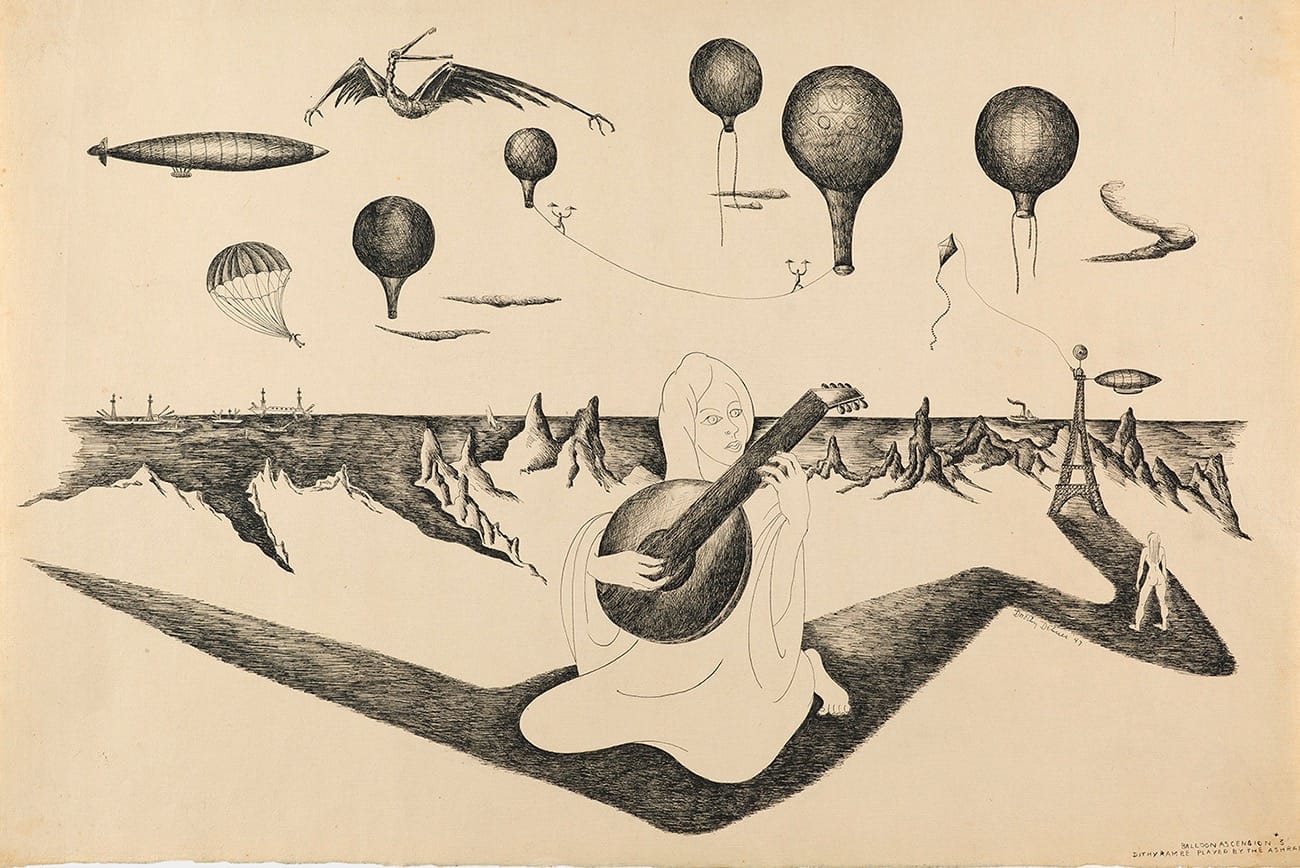

As with times previous, I found myself drawn to a diversity of work: illustrations, studies, human portraiture, animal portraiture, nudes, a couple of surreal landscapes, and inventive, post-war abstract works. I was surprised to find the latter, and when I admitted to Katherine Degn of Kraushaar Galleries that I admired her gallery the most of those I had seen that day, she said to me that their emphasis was more on the “drawing” than on the “masters.” This is where I saw a strange dreamscape by Dorothy Dehner titled “Balloon Ascension #3: Dithyrambe Played by the Ashraf” (1947), and a couple works that were not actually drawing: a print from a woodcut by John Storrs “Repose (Reclining Figure Under a Tree)” (ca. 1920); and a black-and-white, abstract work by William Kienbusch, “From the Porch, Cape Split #2” (1972), which might represent an old set of antenna that used to typically line the roofs of houses in the 1970s.

I paid less attention on this trip to works from the European Renaissance, with a couple of notable exceptions. Jacopo Pontormo’s work at Christopher Bishop Fine Art was quite impressive. Pontormo’s double-sided drawings represent four key scenes depicted in paintings that once occupied a loggia (a covered exterior gallery) at Villa Castello and which were lost after the Medici dynasty ended. According to Bishop, the drawings represent complex interconnected mythological narratives that dovetailed with the realpolitik intrigue of Cosimo I, who assumed the Ducal throne of Tuscany as a teenager to continue the reign of the Medici family after the assassination of a cousin, Alessandro.

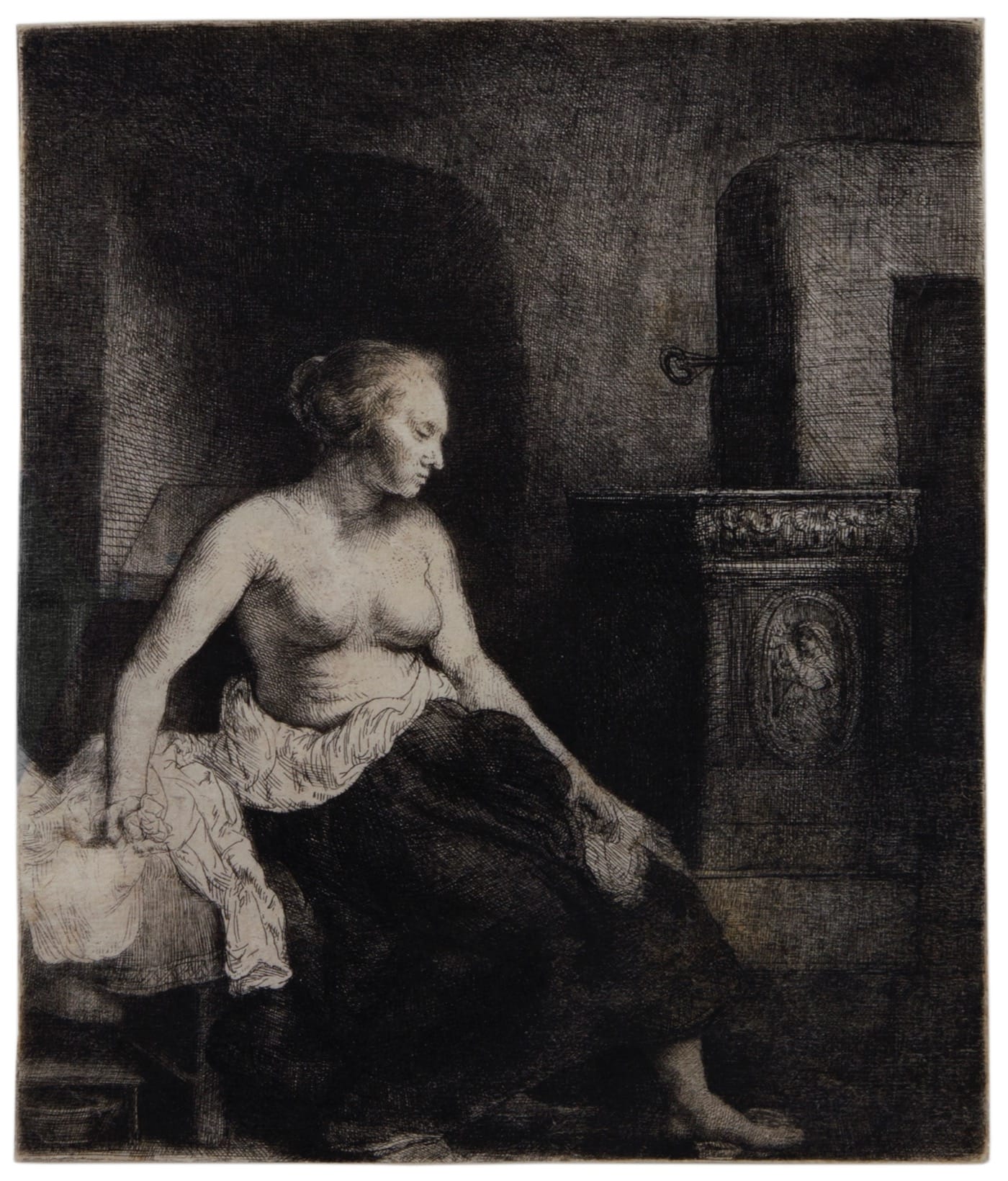

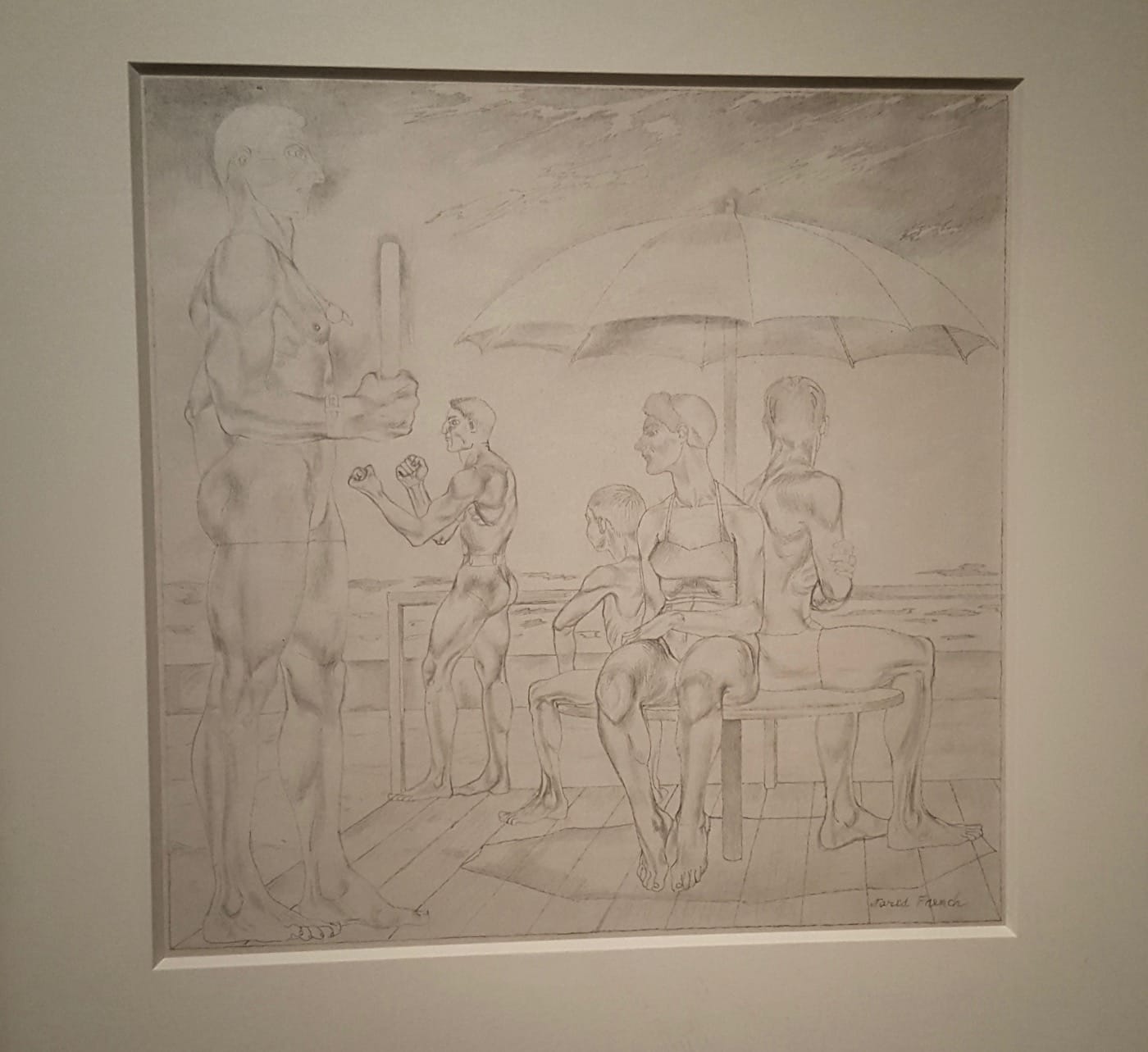

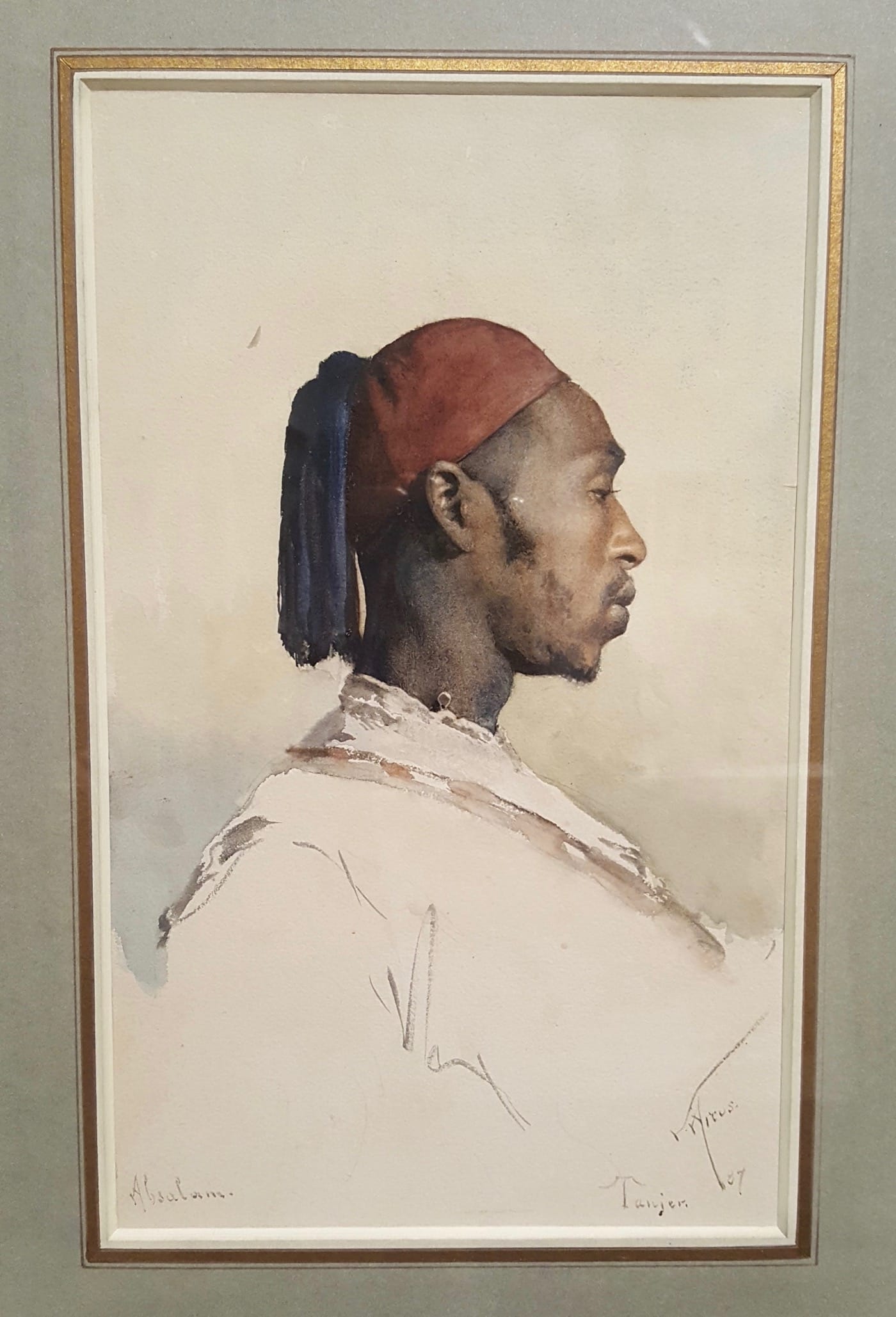

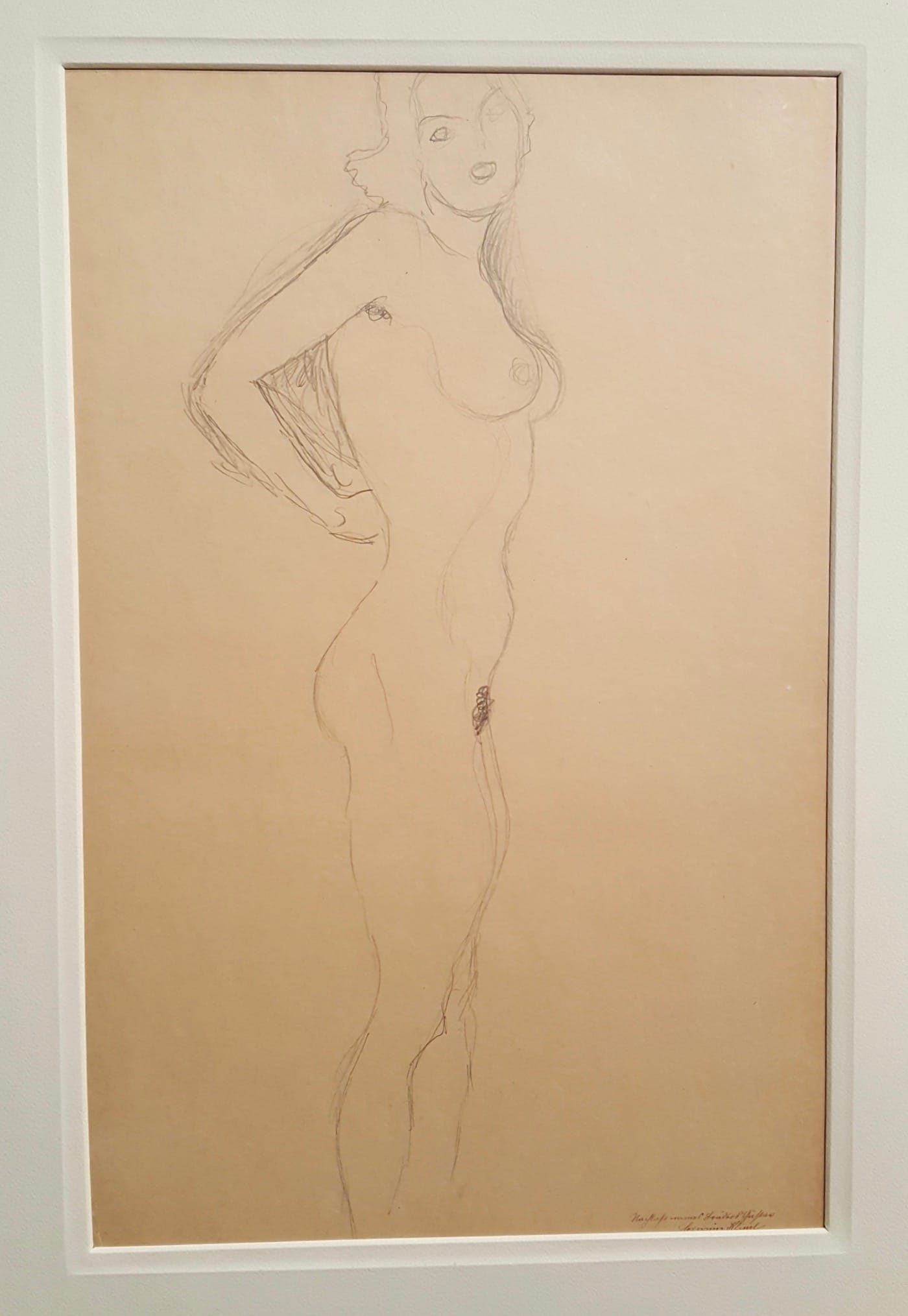

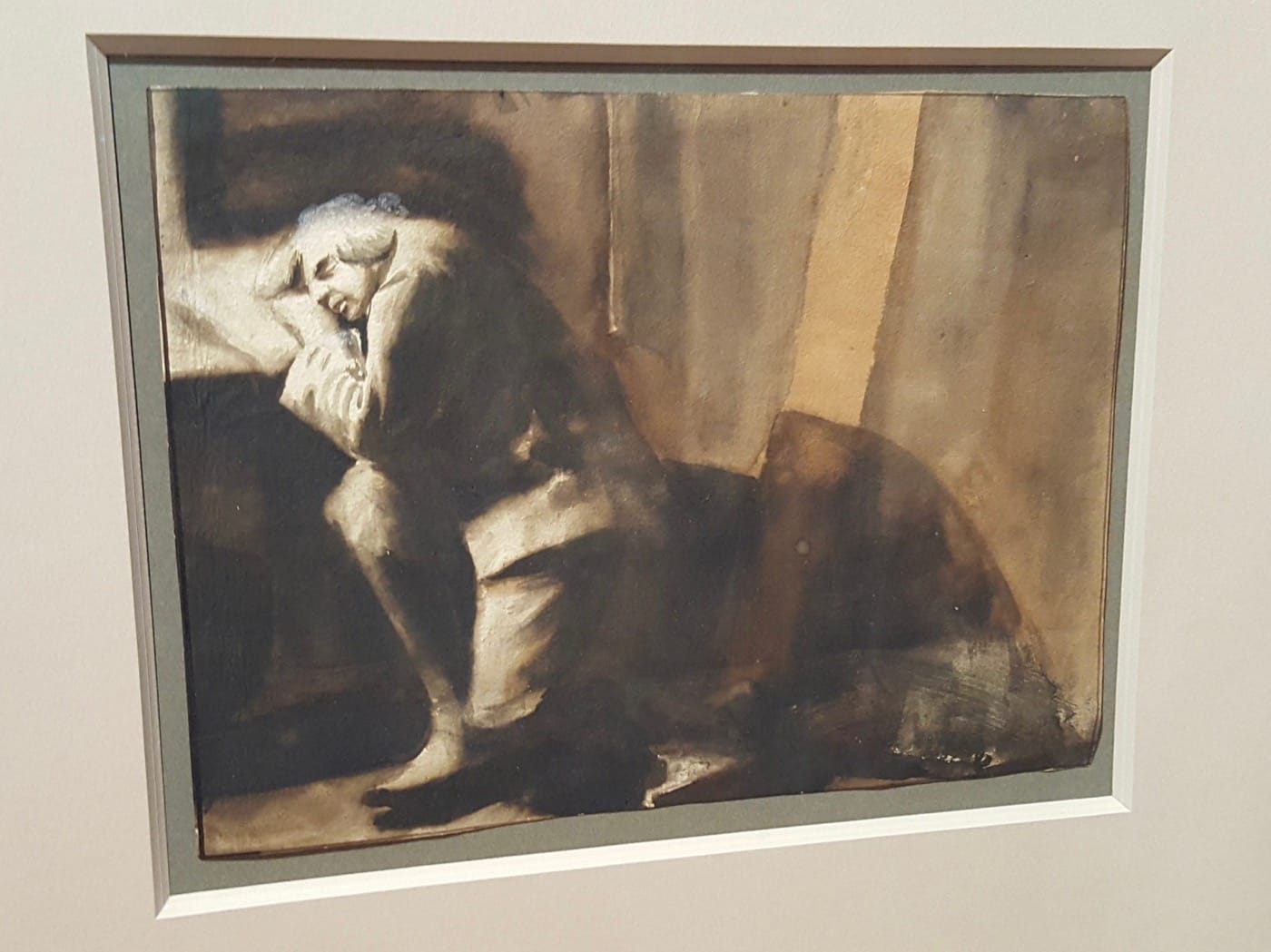

Among my other favorites are a small, reddish study of a lion in repose by Théodore Géricault. It’s simple, but gets the blasé dispassion of the creature when it’s at rest. I was also completely engaged by Rembrandt Van Rijn’s “Woman Sitting Half Dressed Beside a Stove”(1658), an etching and engraving that captures the weariness of the subject. The more I see of Rembrandt, the more I’m convinced that as much as he was a master, he was also an empath. I was surprised to find a portrait of someone who looks like me in Santiago Arcos y Ugalde‘s “Absalam” (1887), on display at Stephen Ongpin Fine Art. Santiago expertly renders the facial hair of the Moroccan man, as well as his quiet self-containment; it’s rare to find this among the work across the fair: a dark-skinned person given this sort of dignity. I was also excited to see the drawing study by Jared French of a painting I’ve seen at the Whitney Museum of American Art: “Study for State Park” (1946). I immediately recognized the drawing because the painting had stayed in my memory years after seeing it — the strained poses of the characters are so strange and yet they seem comfortable in their strangeness.

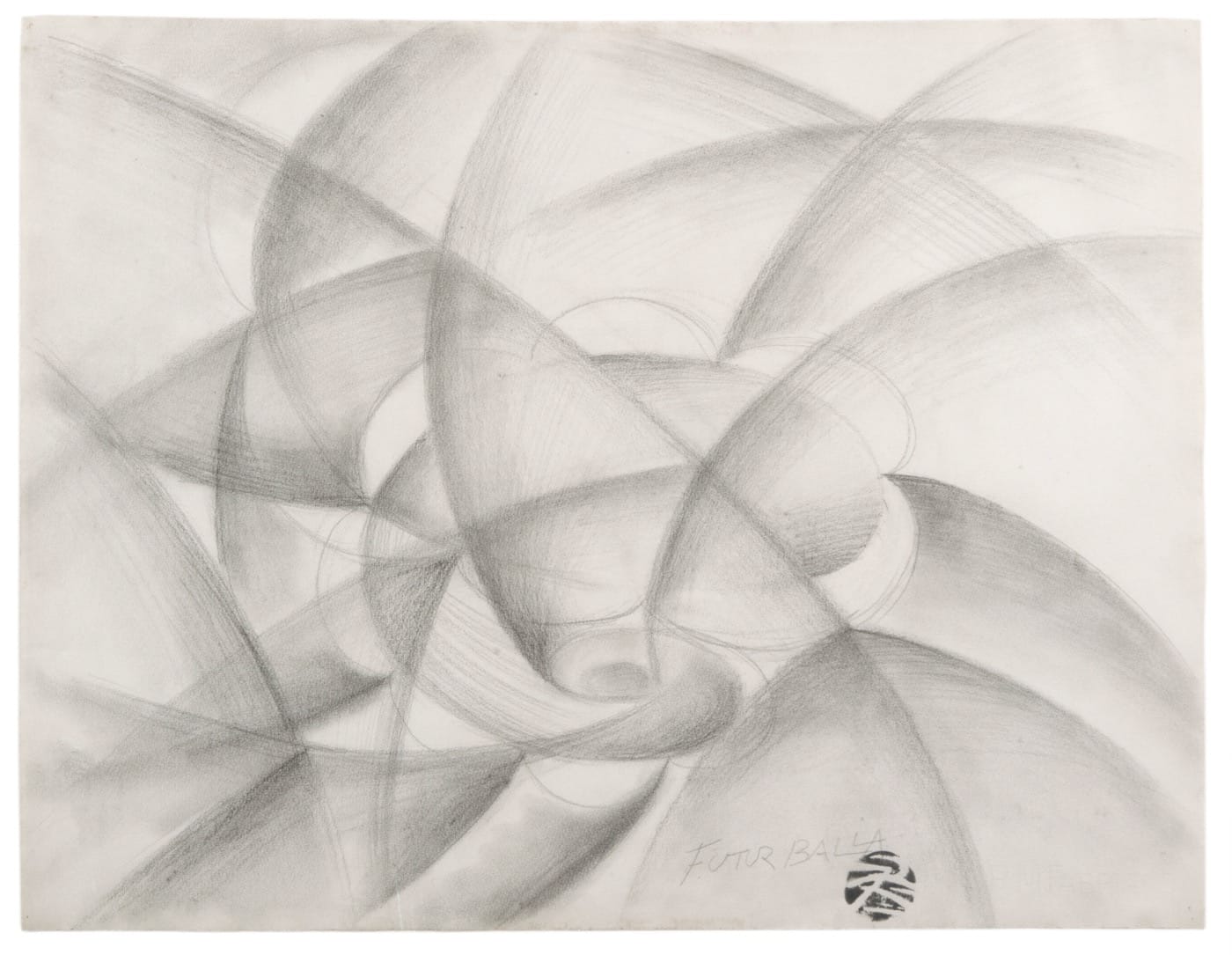

Lastly, I was happy to run into Giacomo Balla’s “Vortice” (ca. 1913-14) at David Tunick. I have for a long time loved the Italian Futurists, particularly Balla, who made several paintings that looked liked swirling squalls of hurly-burly, and this constant activity certainly feels like a foundational feature of modern life, evocative of the way we live now.

Master Drawings in New York continues at several locations in Manhattan through February 3.