Reconsidering Identity in Art

This is the kind of group exhibition that rarely happens in New York — a gathering of artists from different countries, cultures, generations, and aesthetic approaches focused on the construction of identity.

On March 25, 1941, Wifredo Lam (1902–1982) sailed from Marseille, France, to Cuba, where he was born. He was the child of a mixed marriage: his mother was Ana Serafina Castilla, whose legacy was Spanish and African, and his father was Enrique Yam-Lam, who was Cantonese.

He was returning to a country that he had left nearly 20 years earlier, in 1923, when he sailed to Spain. During his journey home, he and his fellow passengers and friends, such as Andre Breton, were detained in Martinique because the Vichy government regarded them as traitors.

It was during this period of detention that he and Breton met the Martinican poet Aime Cesaire, who had written Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land) in 1938.

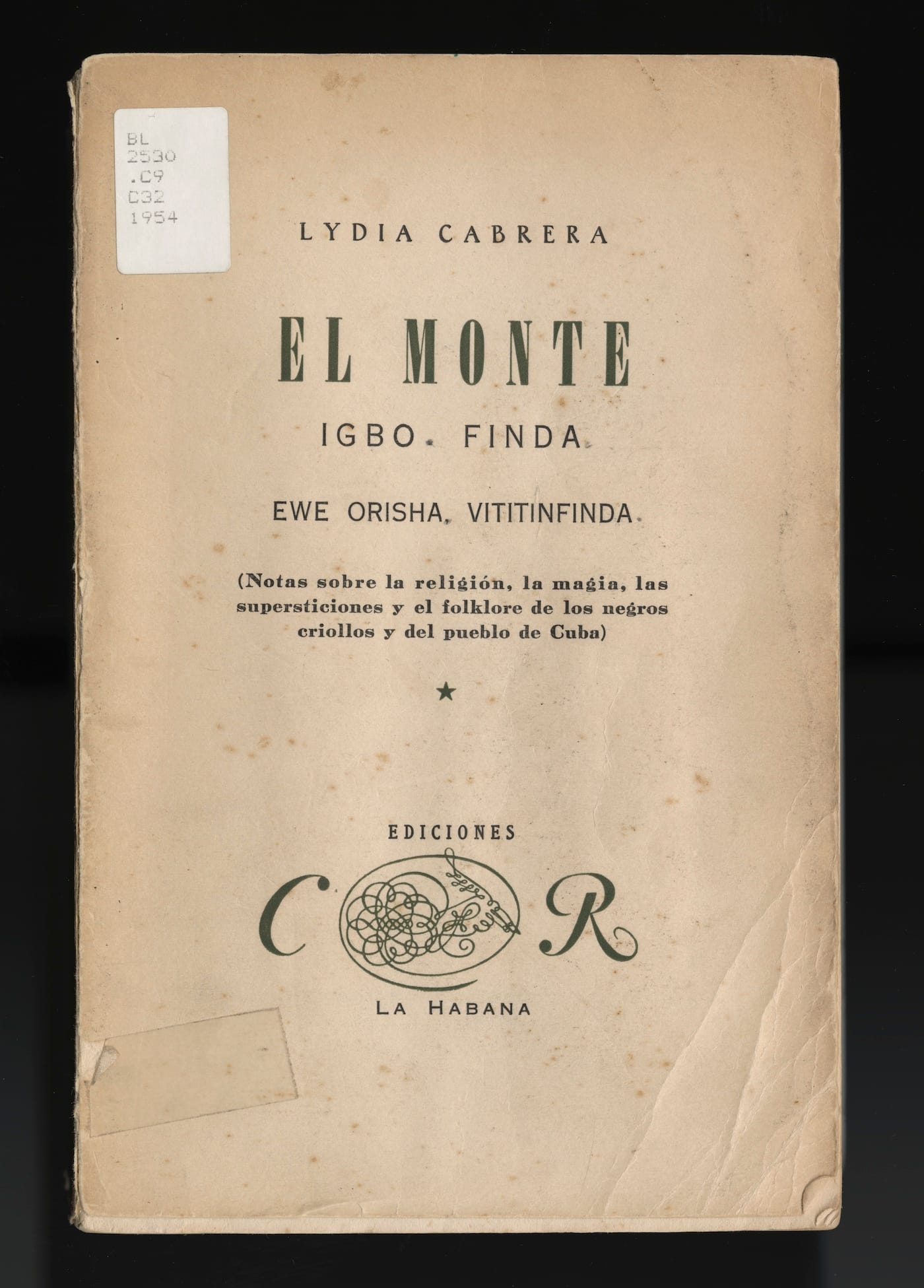

In this book Cesaire used the term “Négritude,” a poetic and theoretical affirmation of African culture as it had manifested itself in the Caribbean. In 1943, Lam provided the illustrations for the Cuban edition, which was translated by Lydia Cabrera. The publication of this signal poem — which was the first and only time that Lam, Cesaire, and Cabrera collaborated — introduced the concept of Négritude to Cuba and its Spanish-speaking population.

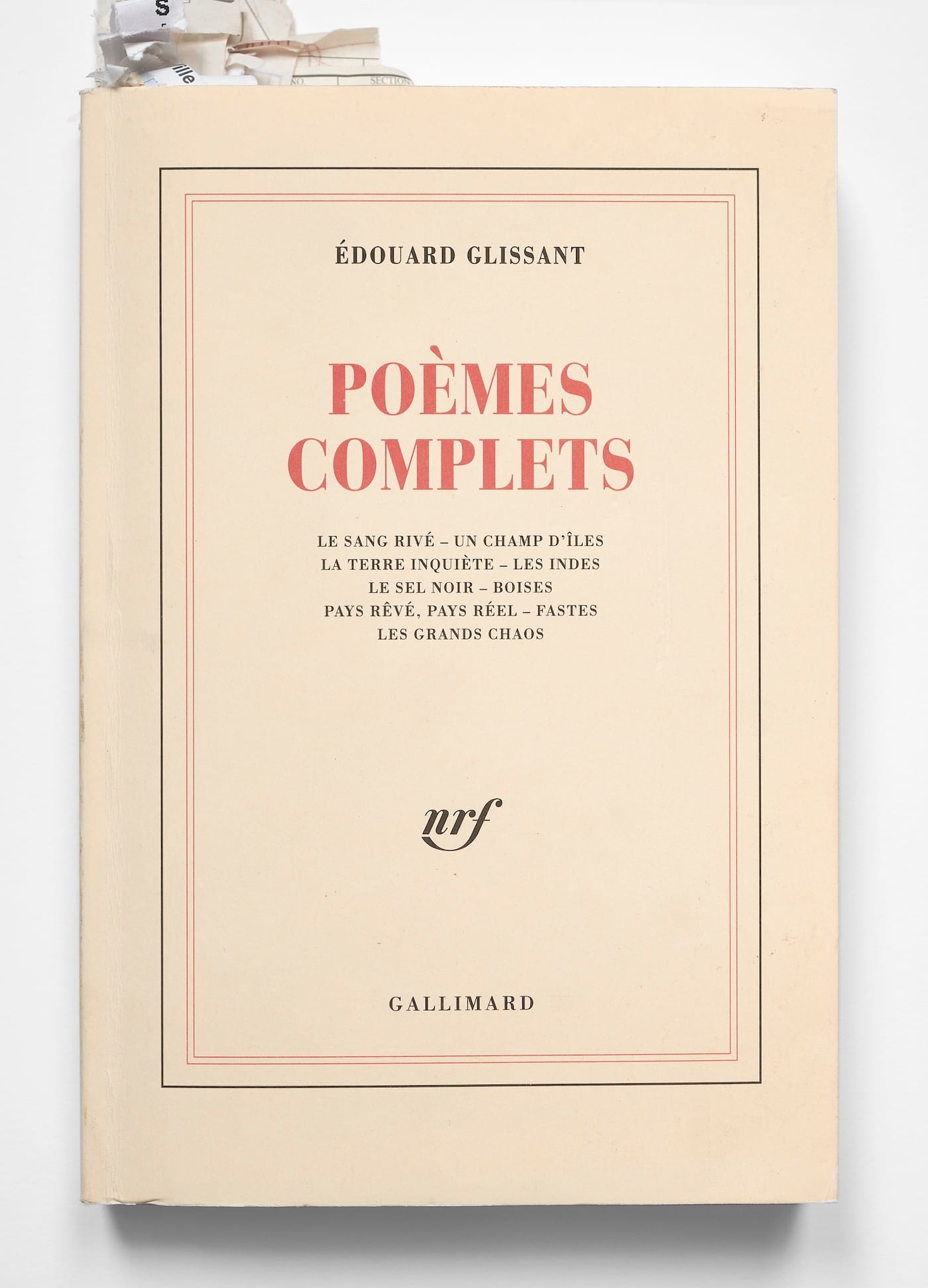

Cesaire was not without his critics. The most important one was Édouard Glissant, a Martinican who was 15 years Cesaire’s junior. In the late 1940s, Glissant began formulating an alternative to Cesaire’s “Négritude.” The term he came up with was “Créolisation.” Cesaire had argued for a Pan-African identity for all people of African descent living in the diaspora, while Glissant believed in a non-hierarchical and local situation in which the children of mixed marriages could construct their own identity. Whereas Cesaire believe in a static sense of identity, Glissant believed in a fluid one.

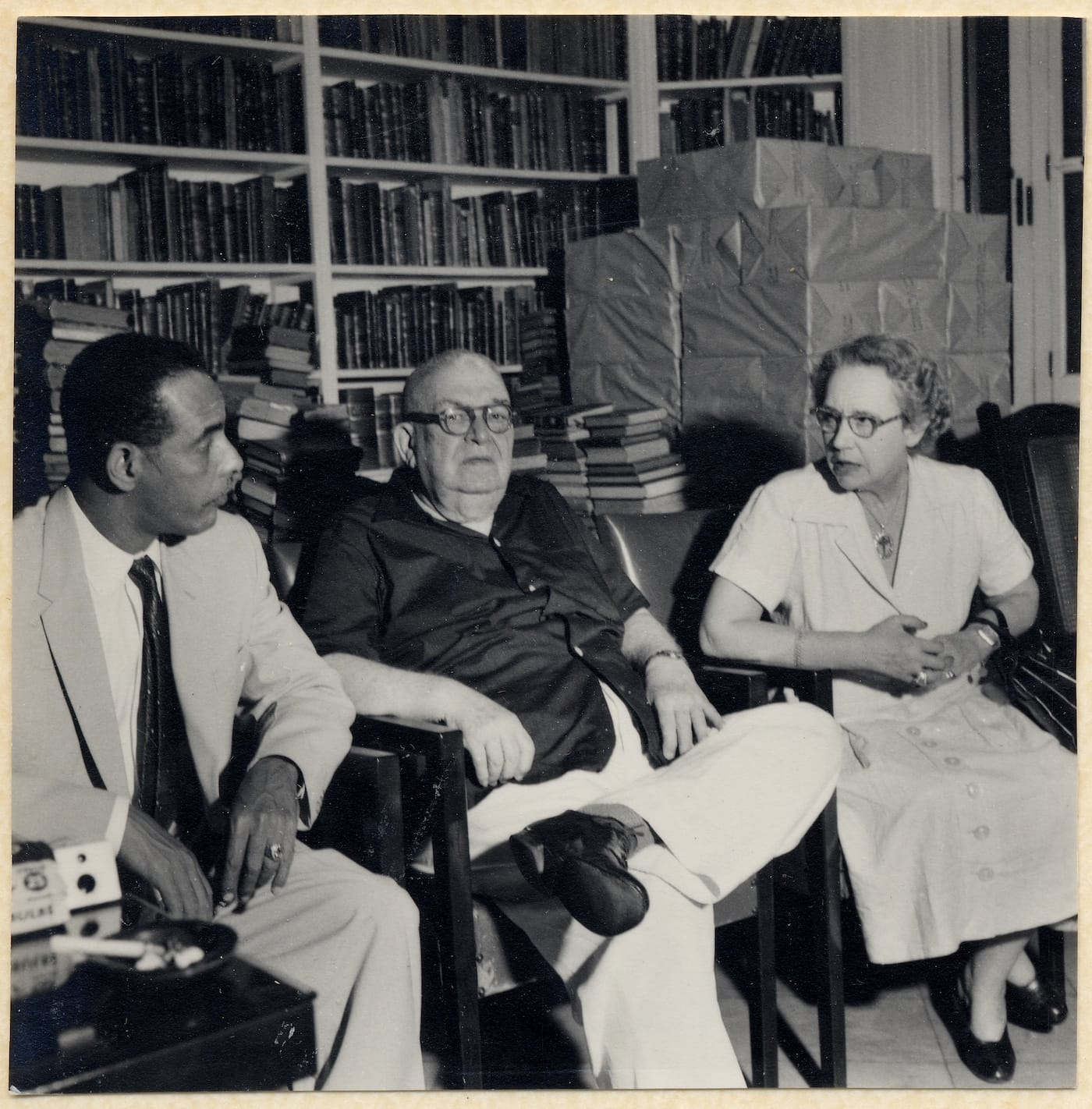

Having written about Lam for the first time in 1988, I was naturally interested in the new exhibition, Lydia Cabrera and Édouard Glissant: Trembling Thinking, at the Americas Society (October 9, 2018–January 12, 2019), curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, Gabriela Rangel, and Asad Raza. Along with early editions of books by Cabrera and Glissant, magazines containing their articles, drawings by Cabrera, and a wonderful film interview with Glissant, the exhibition contains works done in different mediums by Etel Adnan, Kader Attia, Tania Bruguera, Manthia Diawara, Mestre Didi, Melvin Edwards, Simone Fattal, Sylvie Glissant, Koo Jeong A, Wifredo Lam, Marc Latamie, Roberto Matta, Julie Mehretu, Philippe Parreno, Amelia Peláez, Asad Raza, Anri Sala, Antonio Seguí, Diamond Stingily, Elena Tejada-Herrera, Jack Whitten, and Pedro Zylbersztajn. Many of the works — but not all — directly address or deal with Glissant and Cabrera and their considerations of identity.

This is the kind of group exhibition that rarely happens in New York — a gathering of artists from different countries, cultures, generations, and aesthetic approaches focused on the issues surrounding the construction of identity. And while one could quibble about aspects of the show, including the dearth of context provided by the wall text, there was a lot of material to see and think about. If one purpose of a group exhibition is to inspire viewers to learn more about the different artists and writers they have encountered, then this show has more than succeeded.

In the catalog essay, “Trembling Thinking, or Ethnography of the Unknowable,” written jointly, the exhibition’s curators state:

For Cabrera and Glissant, thinking beyond narrow understandings of identity was a practice of necessity — one from which we can learn. But in order to do so, we must listen to both carefully, as we live in a time of defenses erected against “others.”

At a time when the President of the United States can proudly announce that he is a “Nationalist” and the recently elected President of Brazil said that he would rather his son die than be gay, the self-determination of one’s identity has become a matter of life and death, whether it is as blunt and final as a death sentence or the lifelong agony of living a closeted life.

Later, in the same essay, the authors point out that Cabrera asserted that “there is no way to understand Cuba without studying its Black culture,” while Glissant believed “there was always something unknowable, something opaque, inside each person, which, rather than being what divides us, is what links us.” As more and more societies demand conformity and enforce an oppressive view of transparency, Glissant’s “opacity” presents an alternative.

Cabrera and Glissant did not have time to be cynical or ironic. For them, resistance was vital and could be enacted on many different levels and in many different ways, including their own writing, which challenges distinctions. Glissant was a poet, a philosopher, and novelist. Cabrera was a poet, artist, feminist, and prolific scholar of Afro-Cuban religions. If you are at all interested in any of these issues and the intellectual history of the Caribbean, especially in Cuba and Martinique, you should go see Lydia Cabrera and Édouard Glissant: Trembling Thinking.

The exhibition contains Flamariouss (2006), a book collaboration between the Korean artist Koo Jeong A and Glissant, Hommage a Édouard Glissant (2014), an accordion book of colored brushstrokes by Etal Adnan; and a set of 12 small works done in acrylic and sumi ink on rice paper by Jack Whitten for his painting, “Atopolis: For Édouard Glissant” (2014).

In Kader Attia’s video, “Héroes heridos” (2018), series of interviews with refugees and emigre activists living in Spain, one of the interviewees uses the term, “feminization of poverty” to describe the pressure on refugee women to work as prostitutes. As Glissant points out in the film interview, which greets the viewer in the front gallery, capitalism has survived the longest of all systems because it could adapt to world chaos. However, he also believes that all systematized approaches to daily life are ultimately doomed to fail.

While Lam’s relationship to Cesaire is well-known, at least in poetry circles in the US, his relationship to Cabrera is less so. And yet, they lived near each other in Cuba during World War II, and he did at least one portrait of her, “Retrato de Lydia Cabrera (Portrait of Lydia Cabrera)” (1940s).

I think it is worth considering that he painted this portrait while his work was undergoing change, and he had begun to recover aspects of his childhood, which included the memory of his godmother, Antonica Wilson, practicing Santeria, a pantheistic Afro-Cuban religious cult that was a syncretic combination of Yoruba belief and Catholicism. I see this as an example of Glissant’s “créolisation.”

Cabrera published over one hundred books during her lifetime, few of which are available in English. Afro-Cuban Tales (University of Nebraska Press, 2004), translated by Alberto Hernandez-Chiroldes and Lauren Yoder is well worth buying. Cabrera was a brilliant, complex figure whose work should be better known to an international audience.

I like that the curators focused on two individuals rather than one. Cabrera and Glissant agreed on many things but they also went their own way. One was from Cuba and wrote in Spanish while the other was from Martinique and wrote in French. This diversity, which is central to the exhibition, is reflected in the array of material the curators presented.

There are names that will likely be new to the visitor, including Amelia Pelåez, who traveled to France with Cabrera in 1927 to study painting. Her “Mujer con pez (Woman with Fish)” (1948) is a knockout. Another highlight is Tania Bruegera’s figurative sculpture, “Displacement” (1998/2005), which is made from Cuban earth, glue, wood, nails, and textile. A video projected onto the wall documents the sculpture as a costume being worn at a public street performance in Cuba.

In this modestly sized exhibition, the curators introduce us to the multi-layered, complex cultures, traditions, and legacies that are part of the history of the Caribbean, amalgams that underscore the significance of interracial and cultural marriages and the possibilities they beget.

Lydia Cabrera and Édouard Glissant: Trembling Thinking, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, Gabriela Rangel, and Asad Raza continues at the Americas Society (680 Park Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through January 12, 2019.