How John Berger Restores Our Relationship to Art

A new biography on Berger reveals a writer who to this day speaks most eloquently and passionately to our frustrations, fears, hopes, and desires.

As early as the mid-1950s, the art critic John Berger complained about the ways in which art was shown, taught, and written about. The art world — a term he deplored — was too insular, and the art historians and critics did very little to mitigate this. Perhaps most crucially, they failed to share art’s profound connections to human experience. It was no wonder that people expressed little interest in artworks, Berger said in a 1956 article for the New Statesman, because they’ve been led to believe “that such works as do exist have nothing to say to them.” Today, Berger’s demands appear more urgent and his criticisms only truer.

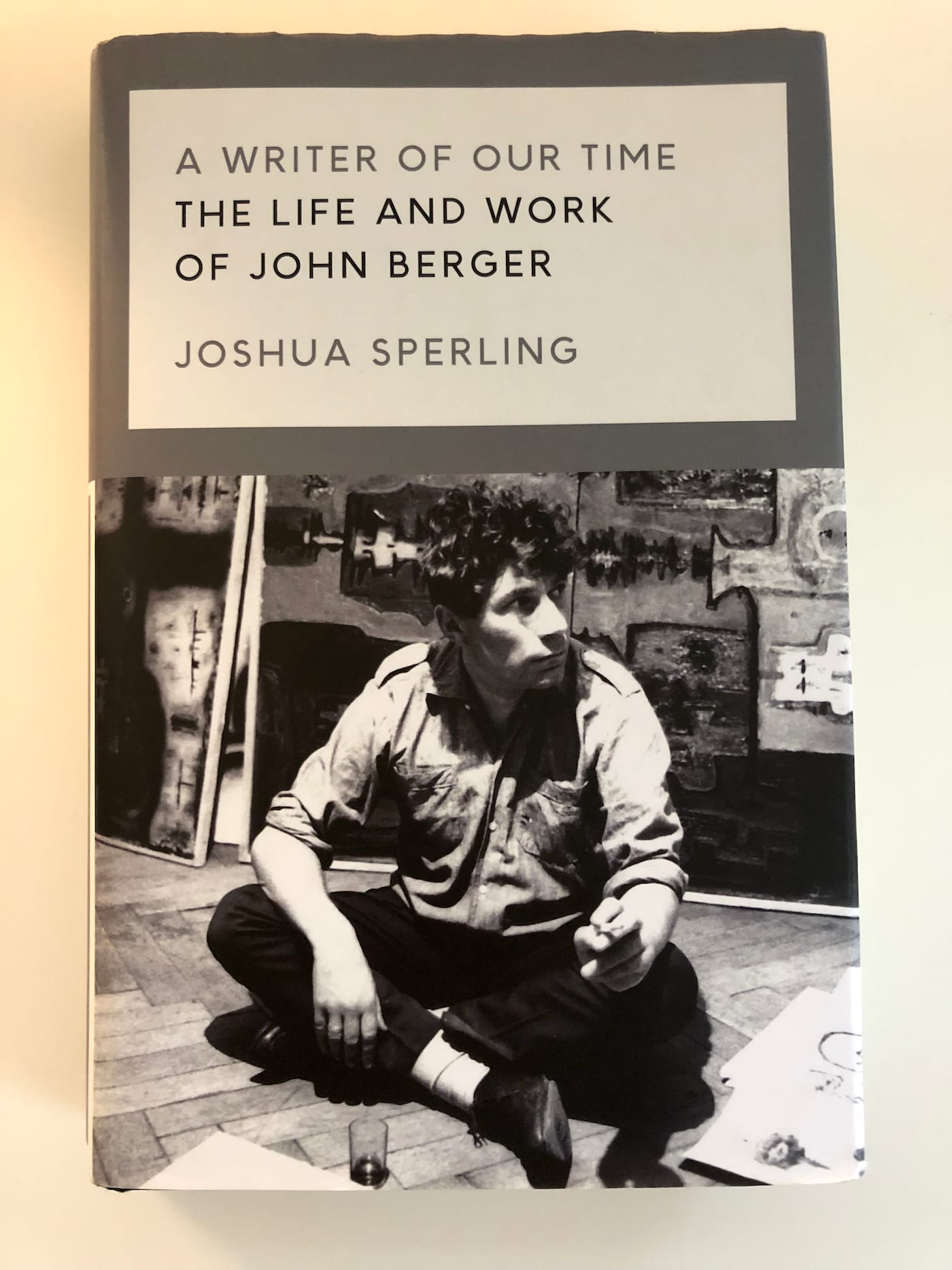

A new biography on Berger — the first published since his death in January of 2017 — reveals a writer who to this day speaks most eloquently and passionately to our frustrations, fears, hopes, and desires. The book, authored by Joshua Sperling and published by Verso, is titled A Writer of Our Time: The Life and Work of John Berger. At Sperling’s Los Angeles book launch, where I led a conversation with him, he explained that the title is a riff on Berger’s first novel, A Painter of Our Time. But the label of “a writer of our time” is also earned.

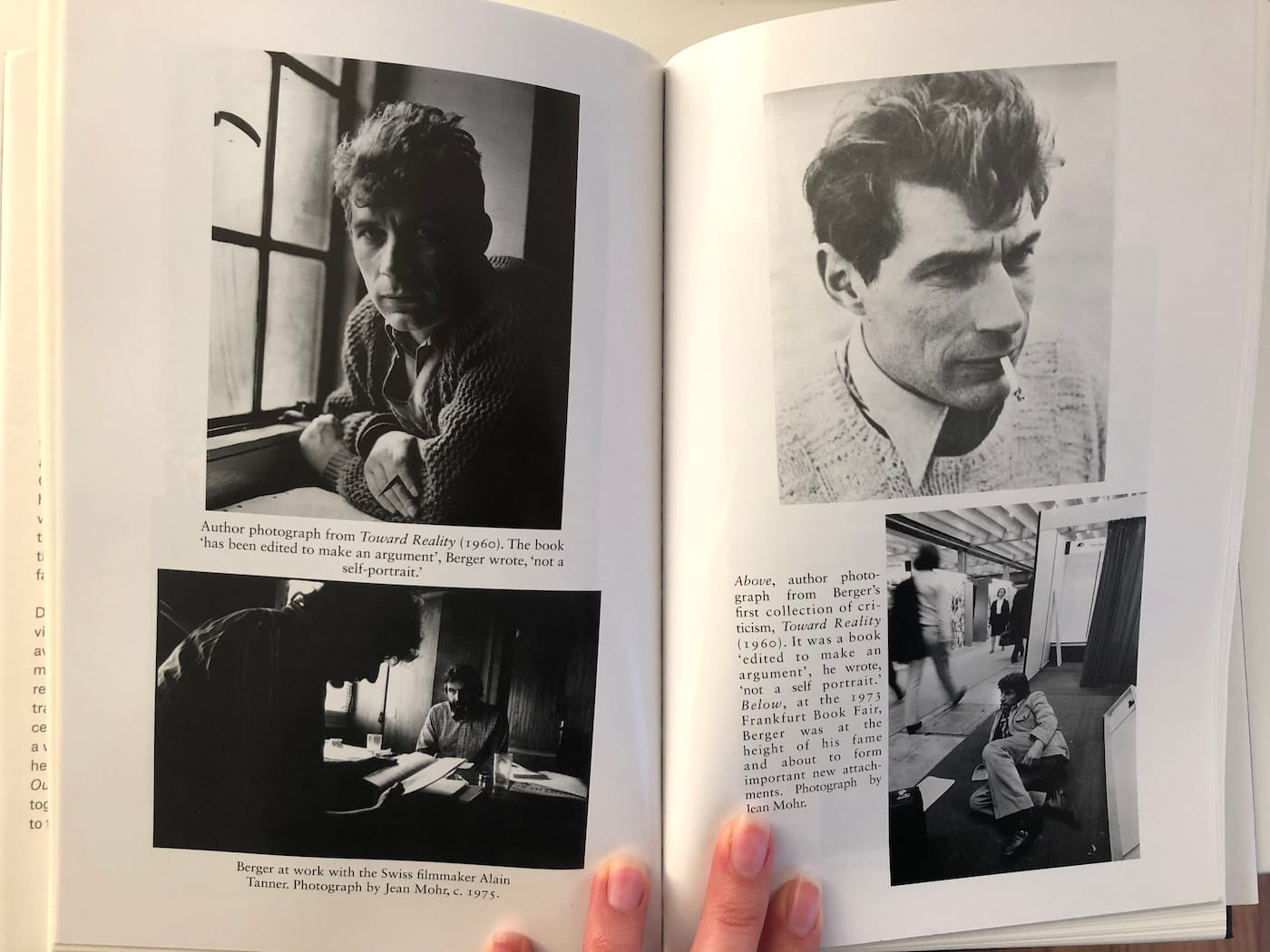

Early on, we are introduced to Berger as a fierce art critic and adamant Marxist in his 20s, raising controversy with his attacks on London’s old-school “museum critics.” Berger did not identify with the fashionable abstract art of the day — it was alienating and apolitical (in fact, for the rest of his life, he showed limited interest for abstract art). Instead, he advocated for a return to social realism: paintings depicting tangible, everyday life. And his call was heard, as he went on to foster a generation of British artists who would eventually be known as the “Kitchen Sink” painters, even organizing an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery.

Moving into his 30s and the 1960s, Berger let go of his grip on social realism and opened his horizons to modernist art. Disappointed with the work of contemporary artists, including those he had cultivated, he turned his attention to artists like Manet, Picasso, and van Gogh. “No longer championing the coming art of the future,” Sperling writes, “he now championed what was lost but revolutionary in the art of the past.” And it seems, with few exceptions, that Berger’s eye stayed on the past for the remainder of his art writing career.

Today it might seem strange for an art critic to focus most of their energies on dead artists. But Berger found clarity in the past. As he once articulated in a 1973 essay on the 16th-century Grünewald altarpiece, engaging with artworks from even centuries ago helps to illuminate our present condition simply by paying attention to our reactions and how we look. “I was anxious to place it historically,” he writes of his initial encounter with the altarpiece. “Now I have been forced to place myself historically.” While Berger was no longer wedded to a social realist aesthetic, he carried with him a belief from his early criticism: that meaningful art will always connect with some aspect of human experience.

But Berger also accomplished something more: he restored a sense of connection to the past in a capitalist culture that was anxiously moving forward. “In an age otherwise characterized by belatedness and alienated repetition, his whole project was to return art to its origins, to rediscover the aura of shared moments and places, and to reinvest experience with a sacred meaning that the instant culture of capitalism had removed from it,” Sperling sensitively observes of Berger’s famous 1972 television program Ways of Seeing, in which he spoke about canonical works of art in a personable way. “It was a personal, artistic and intellectual programme of reenchantment.”

Berger continues to enchant me (and not just because he was very handsome). If you, like me, have taken an art history class, you might remember the ways in which paintings are coldly dissected into diagonals and paths of light. Or how they are relegated to movements and memorized into compartments. Berger, on the other hand, brings the past into the present. He places trust in what we see on our own terms, rather than spoon-feeding us art historical terms.

Throughout the biography, Sperling illuminates how Berger’s own life and social circumstances interweaved into and informed his writing. For me, A Writer of Our Time put much of what I love about Berger into context. And this is especially true in the last couple of chapters, which make up the most beautiful section of the book.

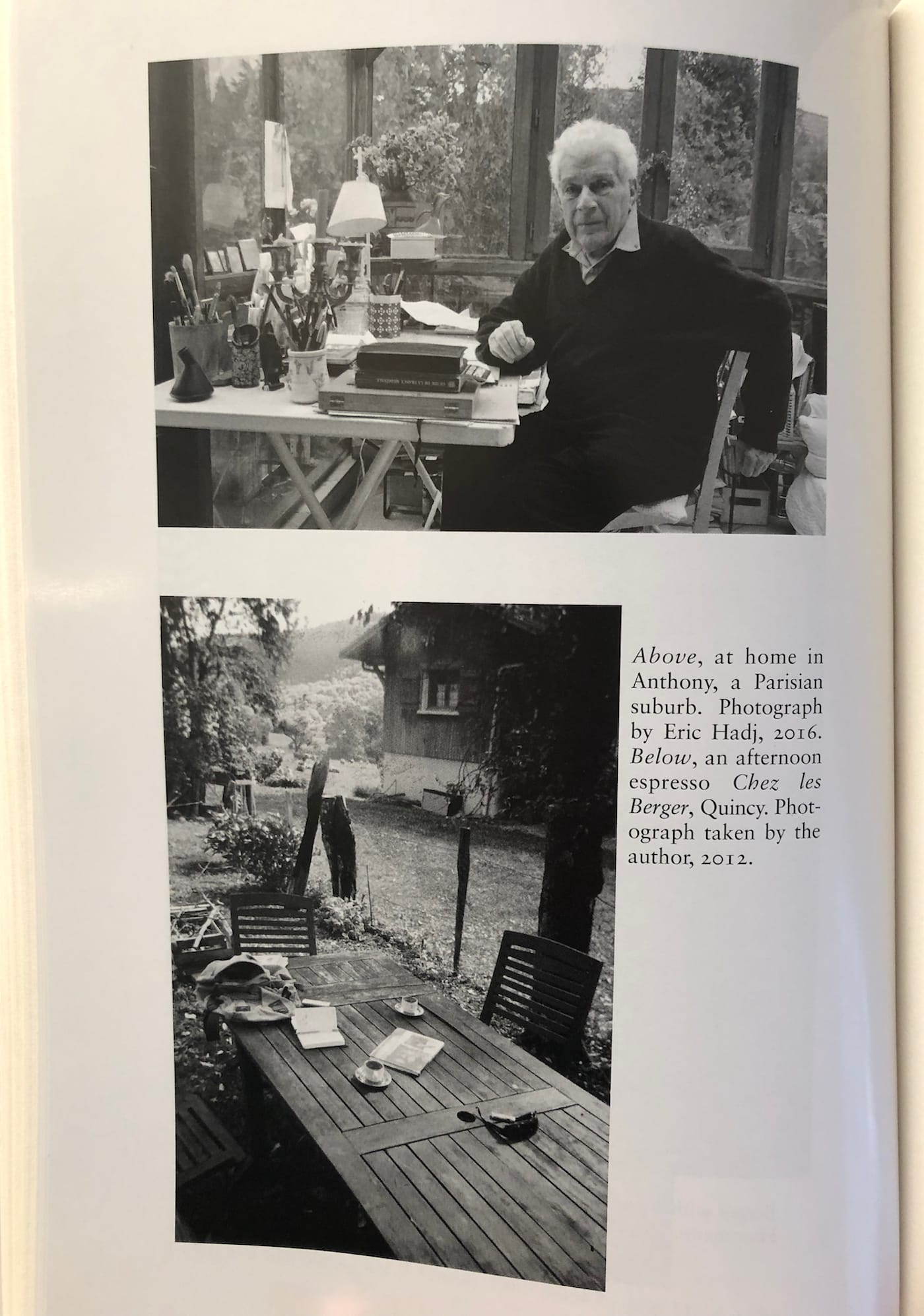

Moving into his 40s and the 1970s, Berger became, in Sperling’s words, “softer.” He became invested in ideas of love and hope, and how art could bring us unity and wholeness in fragmented times. This shift also coincides with Berger’s move to rural France, where he would settle for the remainder of his life. He had never identified with the British — in fact, he had many qualms with them — and it wasn’t until the age of 48, in the village of Quincy, that he felt like he belonged. “I feel at home here in a way I have felt nowhere else,” he said in 1981.

Suddenly it becomes clear that Sperling has been building to this point: the significance of place in Berger’s life and work. On the one hand, he finally felt grounded in a community — he had gained “not only a home but an anchor,” as Sperling puts it. In a fast-paced world, “he was after something durable” and found it. On the other hand, Berger became increasingly interested in how place informed a painter’s vision and how their environs showed up on the canvas, like how the frothy sinks of J.M.W. Turner’s father’s barbershop manifested in his paintings of waves. “Painting, for Berger, was rooted in the experience of sight, and sight was rooted in the local and particular,” Sperling writes. “Visibility takes place somewhere.” (Whereas abstraction was “placeless.”)

Perhaps Berger turned softer because he had finally found resolution: he was no longer searching for a sense of place. But up until that point, paintings — his greatest love — had been the most hospitable, offering him that durability he was after. In the 1990 essay “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye” — an essay that I find myself returning to again and again — he describes the 20th century as “the century of disappearances,” marked by mass emigration, both forced and voluntary. This, he says, explains why film, the most ephemeral of art forms, is the art form of that century. Against this backdrop, paintings provide us with a sense of permanence and place, because they are “static and changeless.”

For some, Berger’s fixation on painting might seem old-fashioned. Others might rightly note that in some ways he was not a writer of our time, particularly in his narrow focus on Western art. But what continues to resonate, at least for me, is Berger’s broader vision for our relationship to art: that it can be deeply revealing of our history, where we came from, and where we strive to belong. In an age of flashy, obscenely expensive art, it is easy to forget this. In that sense, Berger’s writing still serves as a compass to realizing that amidst our scattered, continually shifting lives we can find momentary shelter in art.

A Writer of Our Time: The Life and Work of John Berger by Joshua Sperling is now out from Verso.