Refugees Connect Their Personal Stories with a Museum’s Ancient Artifacts

The Global Guides program at the Penn Museum hires recent refugees from the Middle East to give personalized tours. The leader of my tour was Moumena Saradar, a refugee from Syria who has lived in Philadelphia for two years.

PHILADELPHIA — Famous for its world-class collection of ancient Middle Eastern art, the Penn Museum’s newly renovated galleries highlight the wealth of art and innovation that is the cultural heritage of the present-day Middle East. With a particular emphasis on Iraq and Iran, where the museum acquired most of its Middle Eastern objects, this gallery emphasizes the interconnected, global character of the ancient world, in which the trade of goods, skills, and cultural practices spread far beyond any one empire’s borders. Copious texts in these galleries paint a picture of urban societies not unlike our own.

On a Sunday afternoon, I had the privilege of attending the Global Guides program. Launched in tandem with these renovated galleries, the program, which is open to the public, seeks to bridge cultural gaps by inviting Global Guides — all recent refugees from the Middle East — to connect their personal stories with ancient artifacts.

The leader of my tour was Moumena Saradar, a refugee from Syria who has lived in Philadelphia for two years and worked at the Penn Museum for one. She began by describing the urban nature of these ancient sites. The first stop on our tour was Tepe Gawra. Kurdish for “great mound,” Tepe Gawra is a tremendous structure with 21 levels. It was first occupied around 5000 BCE, but has been in constant use for over three millennia. On display is a model of the structure, glass cases full of artifacts, a large photograph of the site, and wall text characterizing this site as a “busy family home.” The wonderful objects in these cases range from a beautiful obsidian cup, so thin and finely crafted that it looks like gray glass, to little clay animal figurines and rattles for children, mostly dating between 4300 and 5500 BCE. Saradar noted that some objects bear the stamp of the creator, with ancient insignias representing each family’s craft, like logos. She showed us a photograph of her grandfather’s shoe-making workshop in Damascus, at which her entire family assisted. It’s an example of the enduring tradition of craft-based family businesses in the contemporary Middle East.

The next station on the tour was Tell Al-‘Ubaid. Dating from 4500 years ago, the site was excavated in Iraq. The objects we saw emphasize the flowering religious lives of the ancient city’s people. Beside an incredible temple column covered in geometric patterns of creamy pink shell and dark stone are flower-shaped clay nails that would have studded the temple walls. They belong to a temple dedicated to Ninhursag, “Lady of the Mountain.” The architectural fragments suggest how majestic this site must have been.

According to Saradar these architectural traditions of mosaic tiles and geometric patterns persist in present-day mosques throughout the Middle East — and contemporary buildings can have deep ties to the ancient cultures in this gallery. She shows us a video of Umayyad Mosque in her home city of Damascus, Syria, and she explains that it was built on ground considered holy for thousands of years. Once the site of a temple dedicated to a Syrian storm god, it was converted into a Roman temple to Jupiter before becoming a mosque. This site is a living example of the mosaic tradition seen in this gallery.

The next site includes artifacts from various parts of the Royal Cemetery of Ur. A silver lyre and a sculpture of a ram perched among flora are from the Great Death Pit; they were found alongside the bodies of 74 individuals who met an unknown end. A less grim and far grander discovery in the same tomb complex is Queen Puabi’s headdress. Containing lapis lazuli, carnelian, and over five pounds of imported gold, it is a testament to the incredible wealth and artistry of Akkadian society.

Gold and jewelry continue to hold significance in Middle Eastern society, particularly within wedding ceremonies — including Saradar’s own. She showed us a picture of her grandmother’s earrings, which have passed down to her. She remarked that Akkadian is the father language of Arabic, and we moved on to the gallery of cuneiform tablets to discuss the importance of writing in Middle Eastern history. Invented by the Sumerian culture in present-day Iraq six thousand years ago, cuneiform is one of the earliest forms of writing. The tablets on display run the gamut of practical applications, from medical texts to school tablets showing students’ fumbling attempts to learn cuneiform. Saradar screened a video of contemporary Arabic calligraphy, and passed around a physical example.

We stop in front of a single, imposing Assyrian relief. This alabaster sculpture stands almost eight feet tall, and shows a mythical, winged figure who appears to pluck a cone or piece of fruit. Even in this gesture, his stance is utterly unyielding, with an emphasis on musculature and strength. Three thousand years ago, the Assyrian empire brought many cultures together under one ruler. Saradar told us that over three miles worth of these reliefs (all originally painted) have been excavated. Though not displayed here, other Assyrian reliefs depict the explicit violence their enemies would face. Together, these images were a form of psychological warfare, showing visitors the fate of those who resist. It’s a fitting reminder that autocracy and propaganda are not a modern phenomenon.

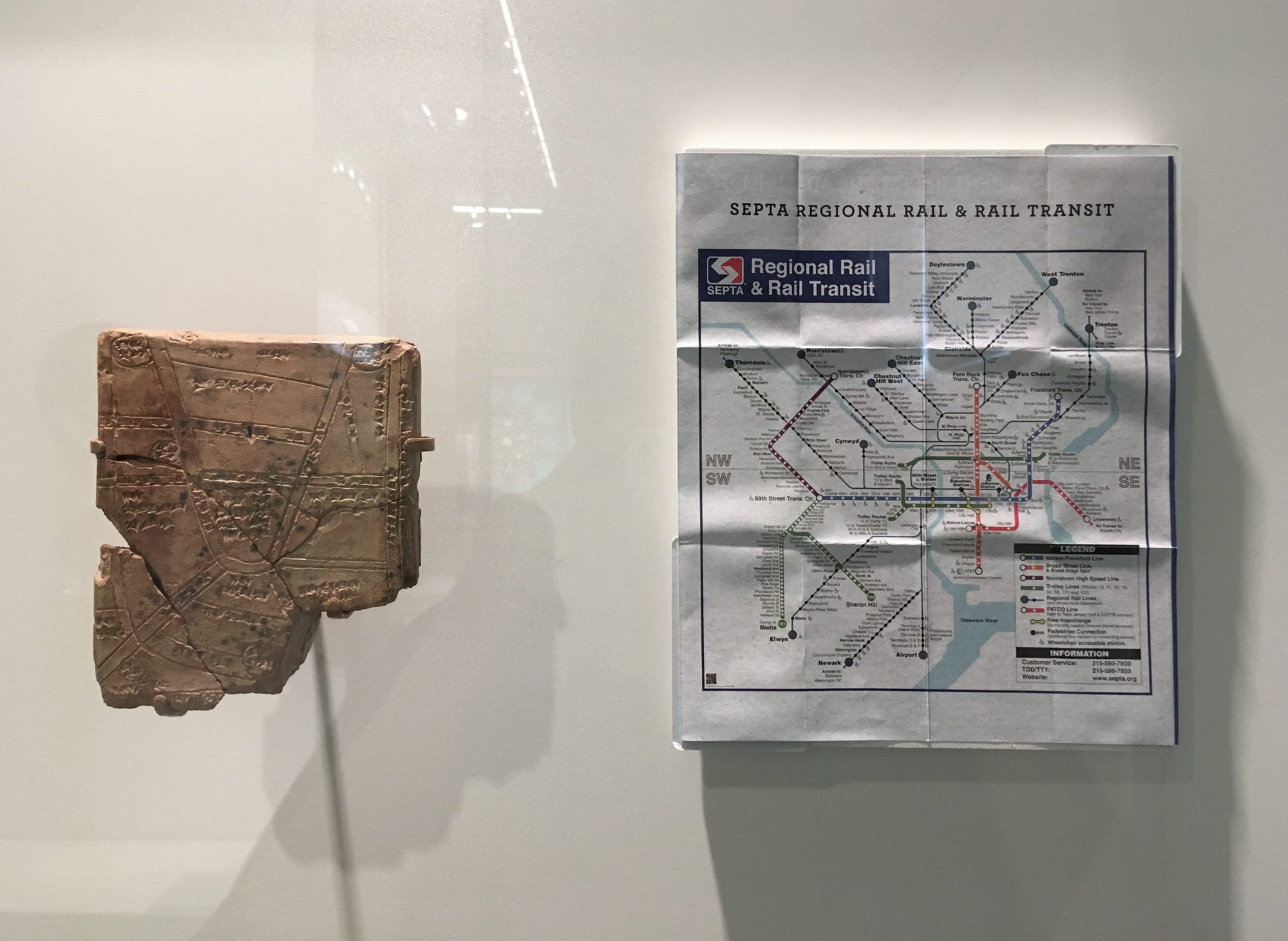

The tour sweetly concluded with a case containing a Philadelphia public transit map alongside an ancient map made of clay and marked with cuneiform. Their similarities in sprawling and succinct routes are a tender reminder that the past is not so different, and that our needs and desires are not so dissimilar. Saradar left us with a story about her first few weeks in Philadelphia: how she carried around the same SEPTA map everywhere and never felt lost.

Amid heightened public discourse about the ethics of museum acquisitions (see recent protests at the British Museum and the Getty’s feud with an Italian city), it’s difficult for me to experience this gallery without considering the baggage of provenance. The museum asserts that its Middle Eastern objects were acquired fairly and ethically; most are the result of excavations funded by the Penn Museum in collaboration with local governments. The possibility of an ethical excavation seems debatable to me, given the fact that many of these excavations occurred against a backdrop of strife-ridden fallout from British colonial rule, and were co-sponsored by the British Museum. Yet my trip to the Penn Museum complicated my feelings, not least because of Saradar’s thoughts; after the tour, I asked her opinion of the museum’s program and her experiences as a refugee in Philadelphia.

For Saradar, the Penn Museum has become a home away from home, a safe place where she has ample time and space to mull over her feelings about Syria and her cultural heritage — issues she says she didn’t consider when she lived in Syria, but are powerful and potent now that she lives in the United States. Heritage tied to her land means more to her now that it is inaccessible, and so these artifacts — and the Penn Museum itself — have become cultural ambassadors within her own immigration story. Though she recognizes that many others in her local network of Syrian and Iraqi refugees feel differently, she is content with the museum’s ownership of these objects. There, she says, they are safe from destruction and war. Saradar added that programs like the Global Guides are innovative ways for museums to create real, positive change through their artifact collections. I was shocked to discover that around half of the program’s participants don’t know a single person from the Middle East, according to exit surveys. This showcases the dire need for such programming, particularly at a museum that serves a wide population beyond Philadelphia.

As someone who has revisited the Chinese Art galleries of the Penn Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art whenever I felt too untethered from my heritage, I firmly believe in the power of museums to promote a very particular sense of intimacy with history, for which I have yet to find an adequate replacement. In this era of the rightfully rigorous critique of many museums’ ill-gotten goods, thoughtful programming and context are paramount for healing and cross-cultural understanding.

Saradar is no stranger to a global, itinerant life — though originally from Syria, she spent her formative years in Nigeria, where she became fluent in English at an early age and picked up some Hausa, though she says it’s a bit rusty from disuse. At 17, she returned to Syria, where she went to high school and college for lab science before marrying and traveling to Saudi Arabia with her husband. They returned to Syria for a few short years, where they began building their new home. When the war seemed immanent, Saradar moved with her husband, parents, and five children to Egypt. There, they went through the incredibly long and difficult process of becoming refugees. She and her entire family now live in Northeast Philadelphia.

Although Saradar says she has grown to love Philadelphia, with its neighborly vibe and diverse, global communities, the relocation has been a difficult process for her family. Yet I also sense in her a special kind of confident calmness, an unflappable practicality that she has used to navigate the challenges all refugees must face: to get here, she and each family member underwent a whopping four in-depth interviews with American and UN representatives, and passed an intense screening process that took a year and a half of waiting and wishing for its conclusion. During that time, the slightest contradiction could mean disqualification. Once here, refugees are only legally entitled to 90 days of aid from a social worker to arrange crucial details like housing, employment, medical care, IDs, and social security cards. Saradar speaks of how lucky she feels — to exit Syria with her family intact, and to have proficiency in English, which landed her a job as a medical translator and her current role as a Global Guide.

The most exciting facet of the Global Guides program may be entirely invisible to viewer; it’s something I didn’t consider before speaking to Saradar and program administrators Ellen M. Owens and Kevin Schott. This program accomplishes the hugely significant task of providing jobs specifically for refugees, who often face incredible difficulties finding employment. No less significantly, this job uniquely allows Saradar and her two fellow guides a safe space to narrativize their own stories.

The program has also had an incredibly successful impact on the museum’s staff; Saradar is one of only two Muslim women who work at the Penn Museum. The program is slated to run as long as funding can be secured and to be expanded to each of the other galleries as they are renovated over the coming years. Next on the roster are Mexico, Central America, and Africa. If Global Guides are hired for every gallery, this program will result in a more diverse, inclusive museum staff that culturally reflects the museum’s artifacts. It is a move that other institutions should consider. As the relevance of some museums to the populations they serve is rightfully under question, there can be nothing more relevant than creating jobs for refugees and folding underrepresented communities into the museum’s team.

Global Guides tours at the Penn Museum (3260 South St, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) are free with admission and take place Saturdays and Sundays.