Contemporary Artists Contextualize the Work of Black Panther Photographers

Vanguard Revisited: Poetic Politics & Black Futures highlights Bay Area artists and artist collectives whose work contextualizes the lasting impact of BPP ideology and activism, and the photographs of Ruth-Marion Baruch and Pirkle Jones.

SAN FRANCISCO — Vanguard Revisited: Poetic Politics & Black Futures at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) celebrates a radical photo documentary project that portrayed the Black Panther Party (BPP) for the profound social justice movement it was.

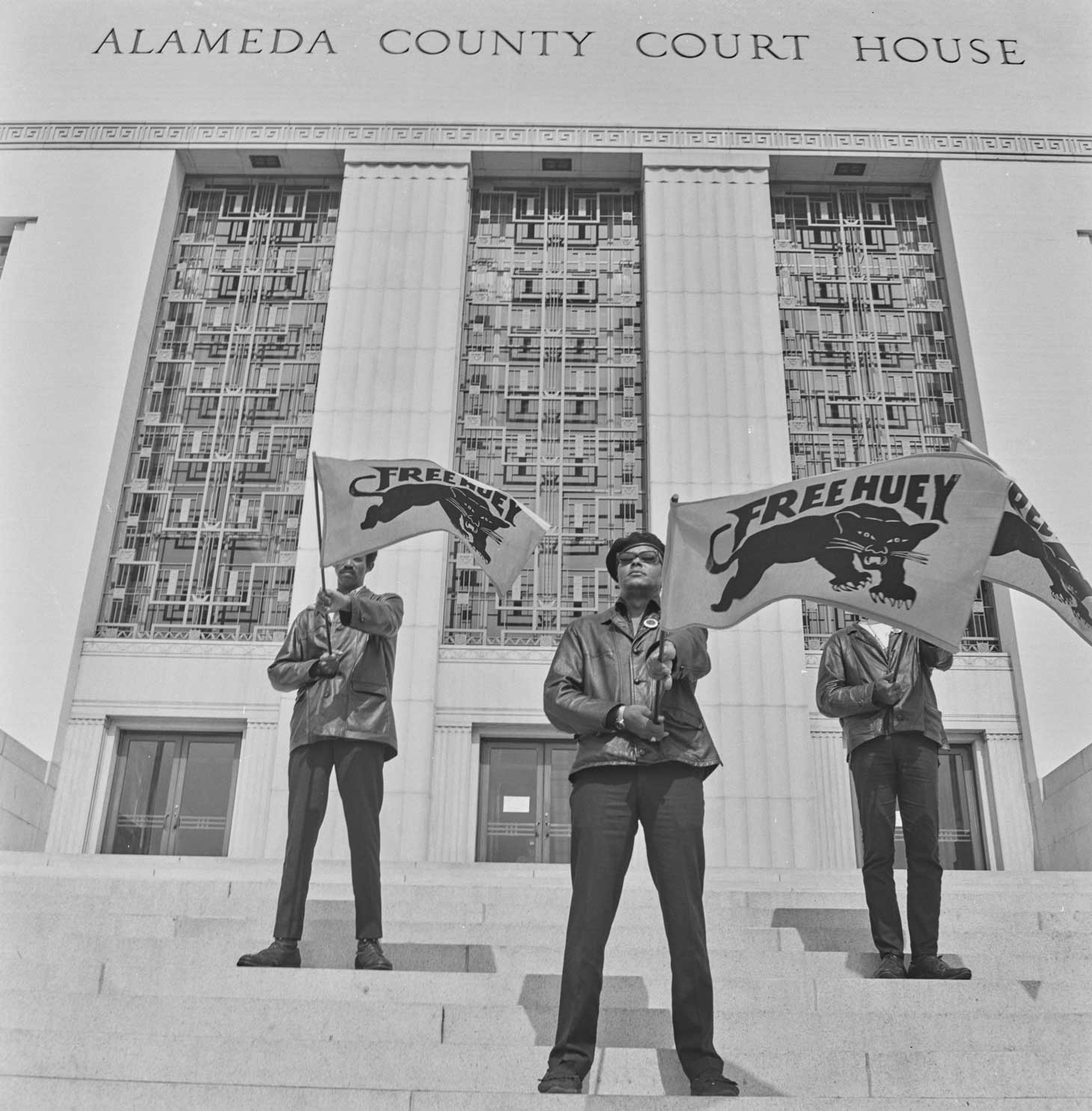

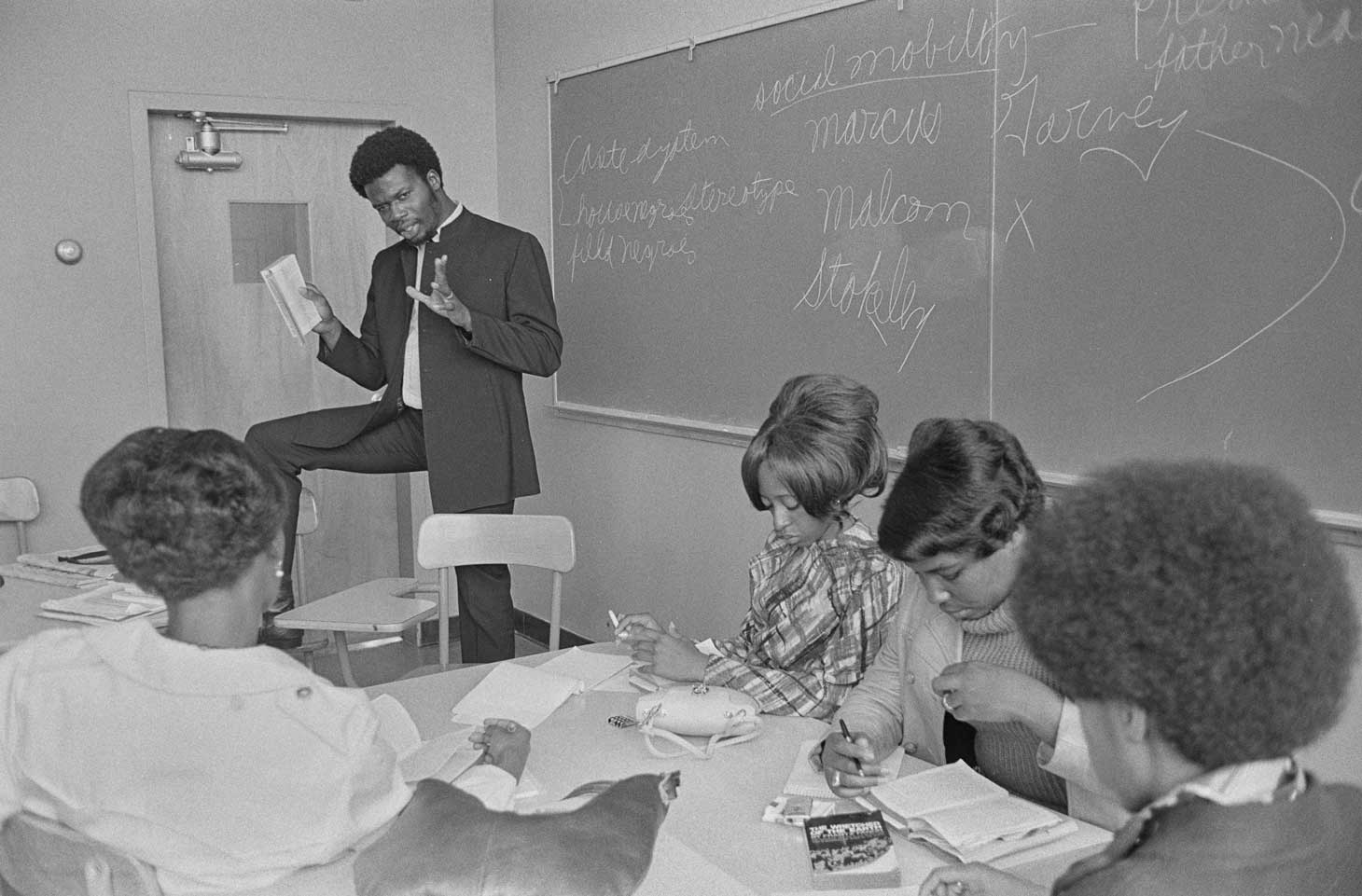

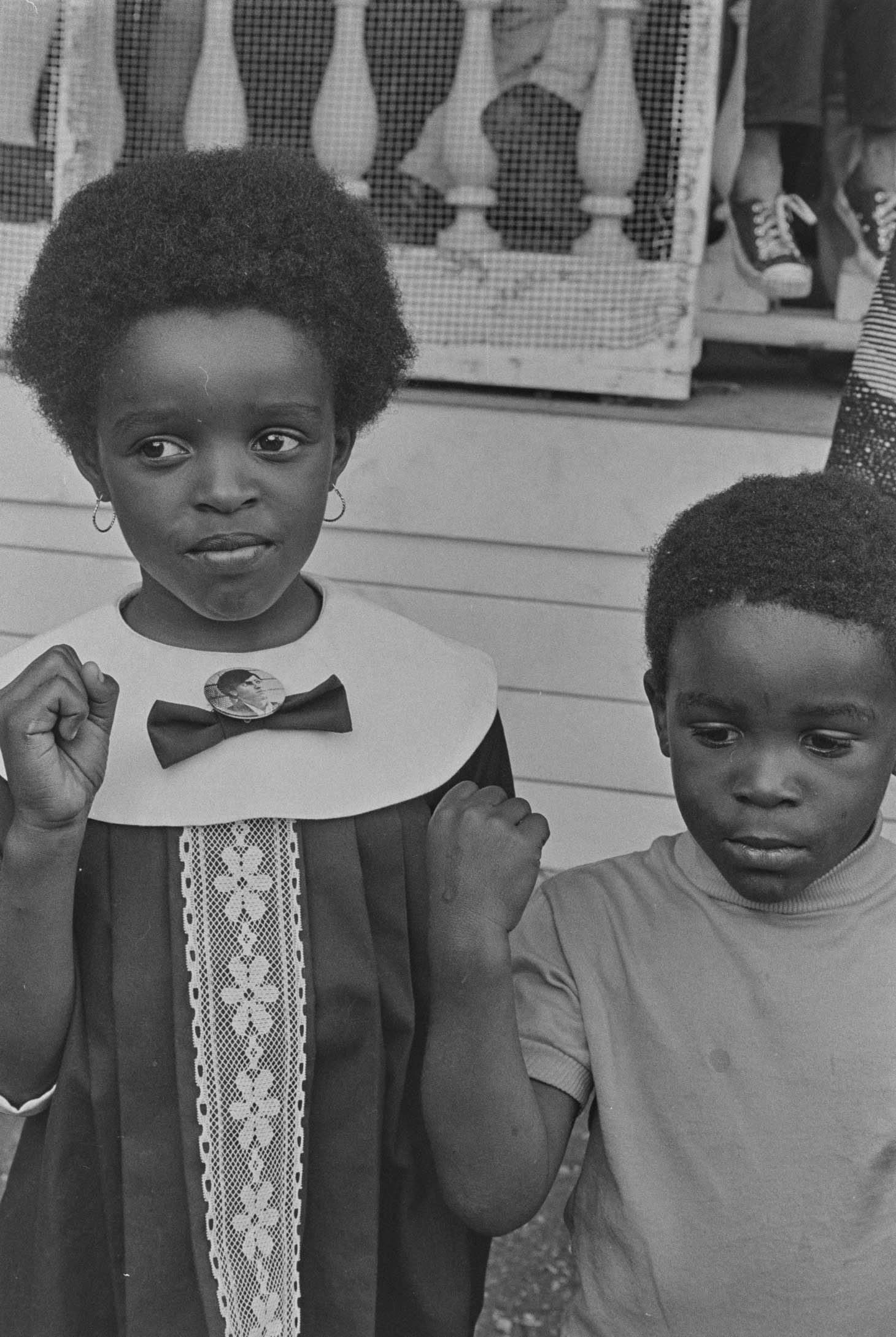

“Radical” is the word that precisely describes the work of photographers Ruth-Marion Baruch and Pirkle Jones, who both studied at SFAI when it was known as the California School of Fine Art. In the production and late-1968 presentation at San Francisco’s de Young Museum, their body of work A Photographic Essay on the Black Panthers, rejected corporate media portrayals of the BPP as what former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover described as “the greatest threat to internal security of the country.” Instead of the terrorizing threat to conservative white America Hoover insisted the BPP was, Baruch and Jones captured scenes of peaceful protest, empowerment, community engagement, and service that formed the foundation of BPP activism. By inviting input on matters of participation and representation from Party members including Kathleen and Eldridge Cleaver, the photographers abandoned journalistic assertions of neutrality that shaped photo documentary and essayistic practices of the day. What emerged is a powerful, lucid visual statement about one of the 20th century’s most important socio-political movements.

Five decades following, Vanguard Revisited confidently holds space that its predecessor did not. Specifically, it highlights four contemporary Bay Area artists and artist collectives whose work contextualizes Baruch and Jones’s photo essay and the lasting impact of BPP ideology and activism.

Tania Balan-Gaubert, Troy Chew, and Nkiruka Oparah, together know as 5/5 (Five fifths) Collective, suggest a domestic setting in their installation “Anybody Home?” (2019). Hung opposite a tastefully ornamented rocking chair are framed photos of couches abandoned on city sidewalks, displayed as portraits would be. The vernacular images suggest the material comforts of home, and the housing insecurity created first by discriminatory home loan practices, and later, unchecked gentrification throughout the Bay Area.

Kija Lucas’s “Grinnell 222” and “Buxton 287,” from the series In Search of Home (2018), take up the physical and psychological effects of uprooting, moving, and establishing roots that many African Americans experienced during the Great Migration. The nuanced taxonomic metaphor Lucas weaves of her family’s movement through 13 states speaks to a desire for grounding and acceptance within the communities they inhabited.

Christopher Martin and Tosha Stimage pursue a less nuanced, but no less powerful approach. Their bold, graphic design-influenced pieces “Black Panther,” “Black Power,” and “A & OP position to Nation” (all 2018) visualize the power of language, and how pervasive symbols are interpreted. Stimage’s monumental white heads centered on a black ground arouse specific references, including 18th-century silhouettes and their sinister photographic offspring mugshots. To non-Black viewers, the muted mirrored heads may read as harmless, but that is not the only interpretation the work brings up. In today’s heavily surveilled social media environment, pictures of Martin’s “Black Power” fly under the censorial radar while “Black Panther” is reliably removed for defying Instagram’s community content standards. Without question, the swastika symbolizes extreme violence enacted against people of color, LGBTQIA+ community members, and people of the Jewish faith. But what does it mean for audiences who identify with the equally empowering Black Panther symbol when it is censored? These pressing questions reinforce how symbols must be considered according to context and experience.

Baruch and Jones’s work debuted in a churning social cauldron: the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Senator Robert F. Kennedy, the death of BPP member Bobby Hutton at the hands of Oakland Police, riots at the Democratic National Convention, athlete protest on the medals podium at the Mexico City Olympics, and in early 1969, the opening of the notorious flawed Harlem on My Mind at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Though pressed by city politicians to cancel the exhibition, de Young Museum director Jack McGregor ultimately relented after Baruch and Jones alerted local art critics to possible censorship. The installation attracted record-setting crowds.

Vanguard Revisited curators — artist Leila Weefur and SFAI students enrolled in the Collaborative Practices course — thoroughly absorbed the social and institutional history that couches the de Young exhibition. As audiences, we witness the range of contemporary aesthetic practices on display and the emphasis placed on contextual understanding. The outcome is an engaging installation that speaks as much to exhibition practice and institutional roles in social justice efforts, as it celebrates the exceptional work of Baruch, Jones, and the contemporary artists who so well represent the Bay Area today.

Vanguard Revisited: Poetic Politics & Black Futures, curated by Leila Weefur and SFAI students, is on at the San Francisco Art Institute through April 7.