Using Collage to Illuminate How People Are Shaped by Identity Strategies

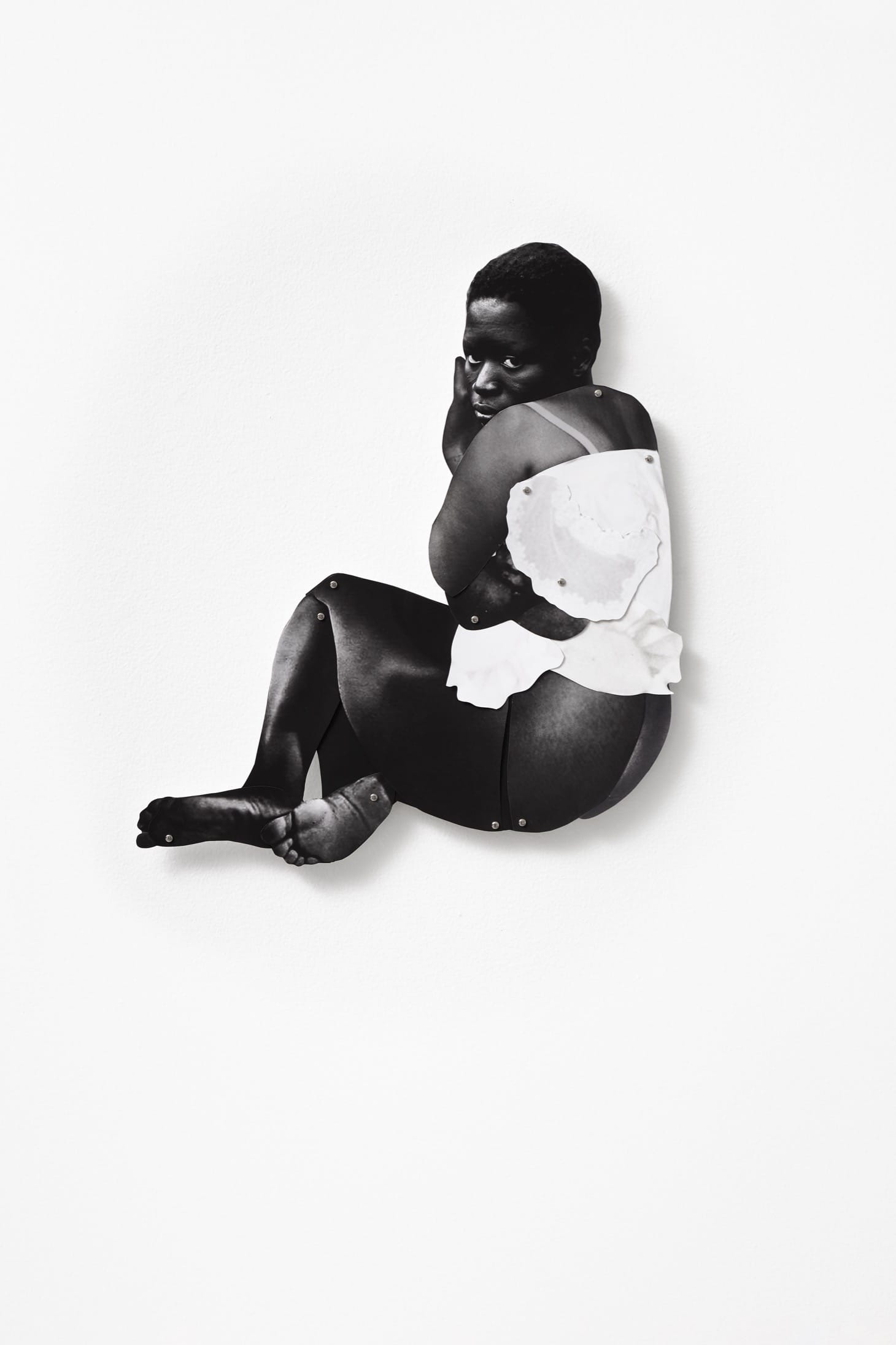

Frida Orupabo's individual collage figures literally expose different layers as if asking the viewer to reflect on what they themselves are composed of.

OSLO, Norway — Black and white digital or paper collages keep clear and minimalist forms. Most of them present isolated figures composed of different parts; they have deformed bodies and usually stare at the viewer as if questioning his or her gaze. And the gaze, the sight, and its power remain important for Norwegian-Nigerian artist Frida Orupabo. “I’m interested in how people see, and how the ways of seeing influence perception of such things as race, sexuality, gender or family” — as she has said in an interview. All of Orupabo’s works present black silhouettes emphasizing subjects important for her exploration: how the black body has been perceived in the past, and how to challenge negative ways of seeing it and thinking about it now. Orupabo’s approach seems particularly intriguing within the Norwegian art context, in which a focus on race is not very present, and the art scene remains mainly white. There are other artists in Norway dealing with similar issues, such as Fadlabi, Victor Mutelekesha, Anawana Haloba, Sandra Mujinga, Wendimagegn Belete, but Orupabo is exceptional in terms of her direct approach.

Born and raised in the small town of Sarpsborg in southern Norway, now living in Oslo, Orupabo started to work with digital collages in 2005 when she got her first computer. Before that, she worked with paint and drawing, but it was her sociology education that gave her a unique approach to the visual arts. After finishing her master degree at the University of Oslo she started to work as a consultant at the Pro Sentret — a service for people who have experience selling or trading sex — an experience that adds sensitivity and empathy to her art.

Frida’s artistic explorations trace how people are shaped by various identity strategies, tensions, and structures of power. Her collages are a way of making these structures visible through what is personal, rather than general. Individual collage figures assembled with a paper pins literally expose different layers as if asking the viewer to reflect on what they themselves are composed of.

But paper is not the only material she uses. Orupabo’s Instagram manifests as a personal digital collage — a combination of stills, text, sound, and video loops. More than 2000 posts vary among fragments from her private life in Norway, the cultural and political history of Nigeria, and random images and pictures with quotations, book covers, or pieces cut from cartoons. Orupabo treats Instagram as a sketchbook, a base of continuously changing inspirations, a practice of storytelling, a form of a personal archive. And the archive becomes here an ambiguous entity: treated half seriously, half in jest playing with the notion of the power by creating alternative personal stories with political overtones.

In 2017 one of her followers invited her to the exhibition A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions at the Serpentine. It was Arthur Jafa. Since that time the artists have collaborated closely on various projects and they take part in the current 58th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale. Since this first exhibition in London, her collages have been shown in New York, Berlin, Stockholm, Warsaw, Prague, and Oslo. A particular distinction between Instagram pictures and physical or material collages presented in the gallery space is important. Instagram images are connected with the collage works in a sense of exploring similar subjects and aesthetics, but here similarities between them end; on a formal level collages belong to a different realm of reality and rules. While on Instagram Orupabo sketches more freely and personally, collages presented in the gallery spaces are definitely more restrained.

The strength of collage images relies on controlled coincidence — the tension between compilation and composition, and shifts from the past to the present. Once a fragment is derived from its original source and combined with other elements, the complication becomes a composition and new meanings and senses come into being. The collage medium sets up a paradox: The original source remains existing and visible, (especially if fragments are analyzed separately) and yet it is no longer there. The absence of the past is present as visible manifestation. It is as if a deconstructed history was opened for new interpretations. But who has the power to define or determine a new sense? Who controls the dominant discourses of perception and influence how most people see and understand things?

Asking the viewer to interpret the collage means asking the viewer to revise and rethink his or her own repository of images and this question might be either answered or just ignored. The ambiguity of time, the simultaneous coexistence of the past and present allowing the confrontation one with another, gives collage the possibility to act as subversive. I would emphasize subtle but crucial words here: possibility to act as subversive, not being subversive. I think about subversion here in the sense of intelligent resistance and opposition, a strategy which relies on imitating or even identifying with the subject of criticism and then shifting the meaning. However, this moment of transition, this moment of shifting the meaning is not always readable; subversion is a kind of indirect criticism full of ambiguity. In that sense subversion might also be understood in the way Judith Butler describes it — as the use of language against its original version, in which a new meaning undermines the existing codes or cultural stereotypes.

Frida Orupabo uses exactly this potential of the collage medium extensively in her practice. The sources of (as she describes it) vintage and colonial images vary from eBay, Tumblr, Pinterest or Google, and it is not that important to the artist from where they were taken. She admits: “the focus is on how I feel about them.” Once transformed into a new piece, photographic compositions are left untitled — always. This creative process that on a surface may look as if erasing names from history, hiding, or silencing the sources, in fact, emphasizes the scale of the colonial violence — an endless possibility of reproducing images as disturbing pieces of evidence .

Orupabo’s intuition here is right: It is history itself that is wrong. If images and documents were produced from the position of privilege and power, by this very fact they carry in themselves errors, misinterpretations and absences. Black history to a large extent is the history of the absence, and the collage medium works exactly to reverse it. Orupabo’s attention seems to be especially focused on black women’s bodies.

Looking at Orupabo’s large, female collage figures hanging on the walls or presented in cabinets, they may remind us of dolls or (from the art history perspective) classical Madonnas, especially women holding children. However, I would rather reflect on two things which seem more important: the material of digital photography, and the imaginary of black women throughout art history. As Deborah Willis noted in her book, The Black Female Body: A Photographic History, until the late 19th century, black women, if they appeared in the Western art, they were mostly “exotic but rarely exalted.” They functioned as backgrounds, as iconographic devices to illustrate other subjects connected with White people’s history. Photography was not less innocent, and accompanied by popular culture, anthropology, ethnology has historically contributed to the ways black woman have been regarded and visualized.

Orupabo’s collages deconstruct this imaginary realm, rather than relating to classical art traditions. What they expose are half-naked, deformed bodies composed with surprising elements; their heads look as if derived from a different reality.

Orupabo’s inspirations are many. From Grada Kilomba she takes a critical approach to memory, trauma, gender, and racism; from Ifi Amadiume new ways of thinking about women’s sexuality and place in history; from Kara Walker an ease in transforming disturbing history into strong and clear language of art; from Francis Bacon a way of showing the body; and from Audre Lorde a strong voice and sensitivity.

Orupabo’s work on image and representation is a lesson on history, but is not an art history nor a history of discourse — that concept of the past that is focused on wars, victories, and structures of power has failed. Such a concept of history cannot reproduce anything more than just violence, real or symbolic. Orupabo’s lessons are about empathy, the ability to listen, see things — and of utmost importance — see human beings. Without these basic abilities, facts and images can be about anything, and a history of perceptual failure can repeat itself endlessly — important knowledge for the interesting times we live in.

A selection of Frida Orupabo’s “Untitled” works is on display at the 2019 Venice Biennale exhibition May You Live in Interesting Times at the Central Pavilion in the Giardini section (Venice, Italy).