The Astonishing Discovery of an Artist’s 9,200 Portraits of an Alternate Queer Self

The previously unknown Polaroids of April Dawn Alison were not just snatched from the jaws of oblivion, but are now in an esteemed museum collection.

SAN FRANCISCO — There’s something fairytale-like, or even cinematic, in the story behind the April Dawn Alison show currently at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) — a tale almost as compelling as the moving, playful, poignant photographs of the show itself. That’s a lot of adjectives for a trove of found Polaroids displayed in a single gallery of the museum, but that smallish space contains multitudes. What should be a modest exhibition instead feels very big, in scope and significance, with images dating back some 50 years that feel totally current, timely, even necessary.

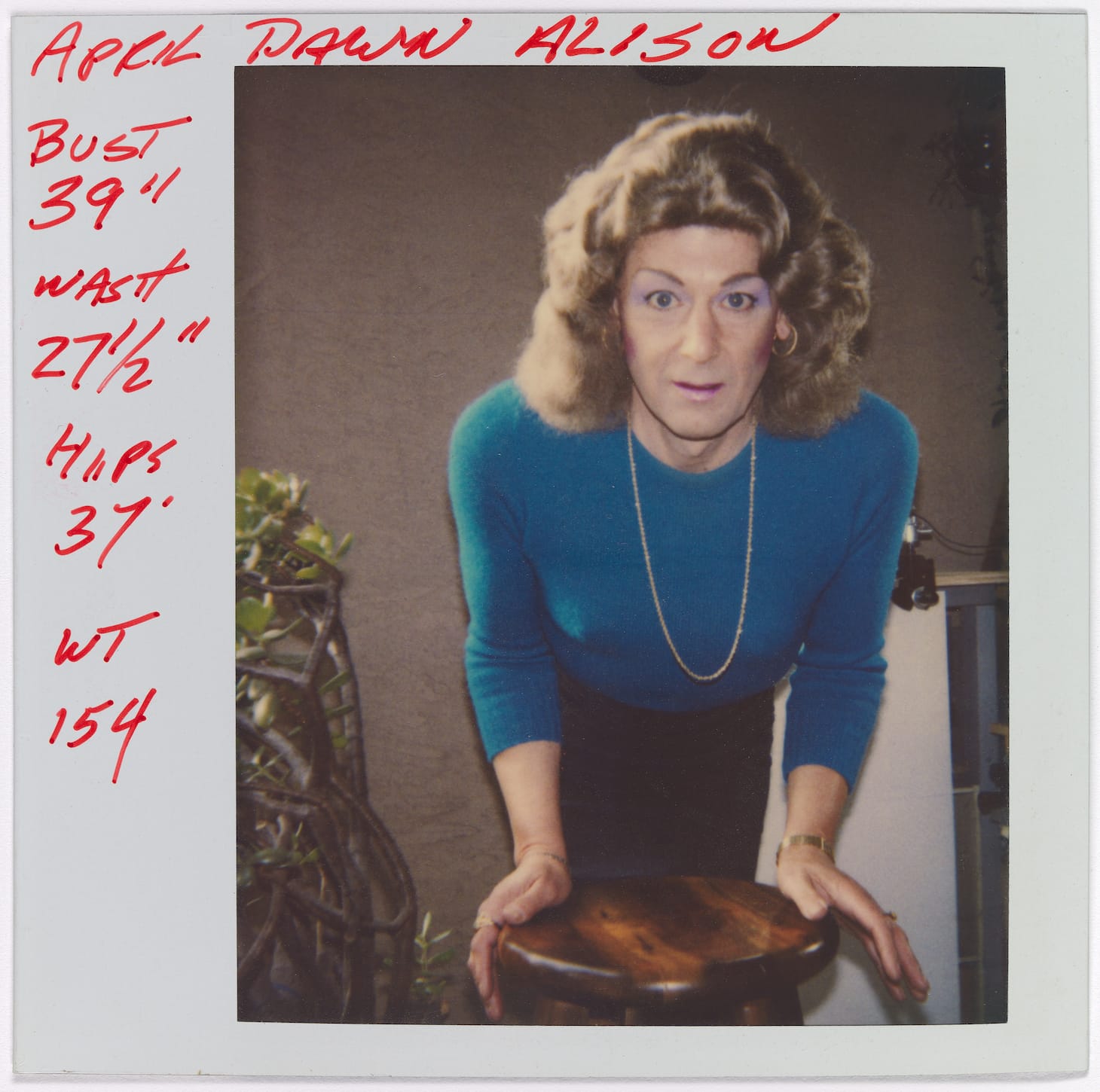

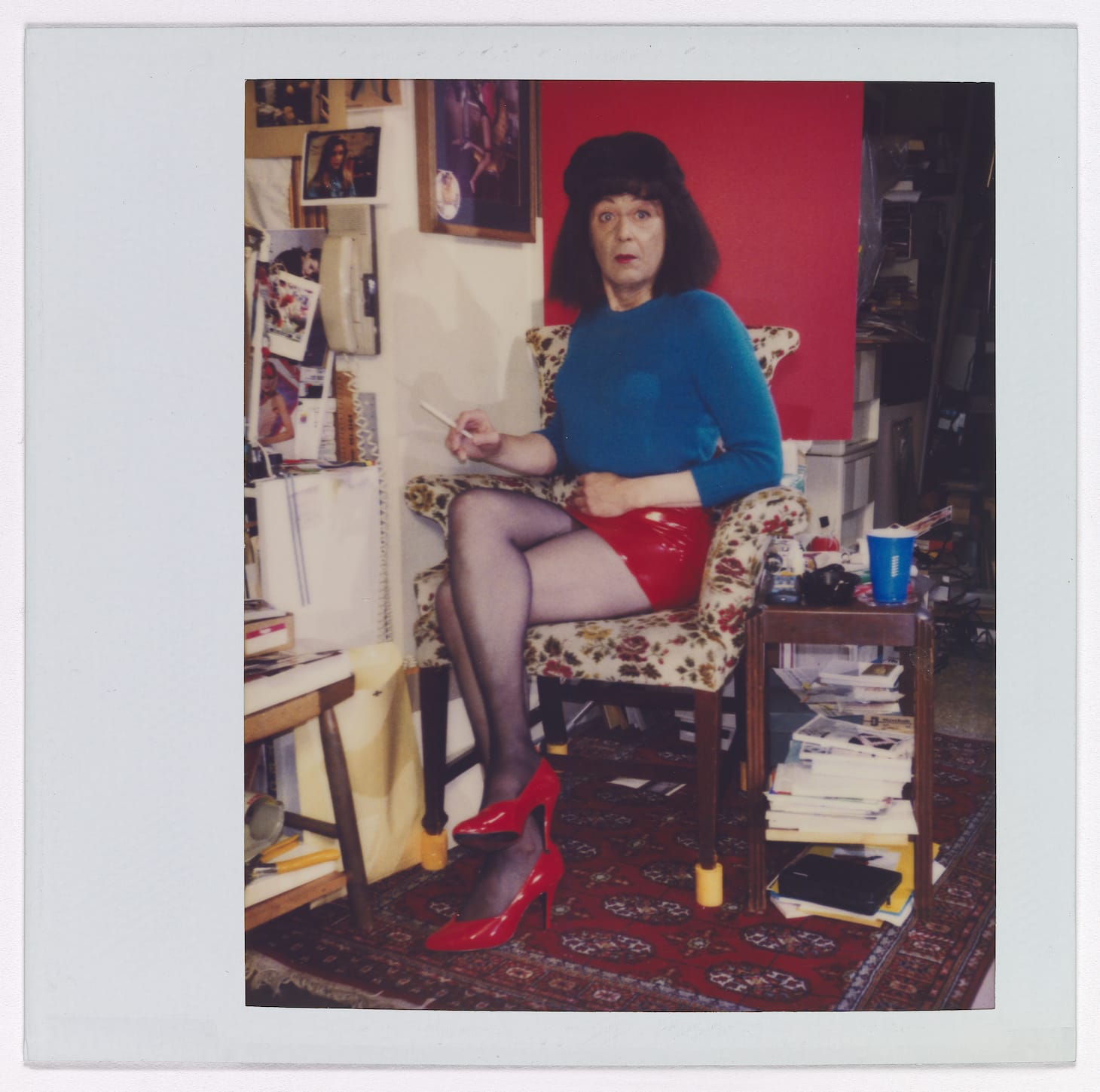

First, the story. A Bronx-born military veteran named Alan (Al) Schaefer lived alone in Oakland, California, where he worked as a commercial photographer by day, and by night (or mornings, or on weekends; we don’t know) created, cultivated, and carefully documented the life and times of an alternate self called April Dawn Alison. By “carefully documented,” I mean 9,200 Polaroids, the vast majority self-portraits, taken over more than 30 years in the life of the artist, beginning in the late ’60s or early ’70s. The photos capture April Dawn Alison as perfect lady, glamor puss, fun gal, sex kitten, domestic goddess, object of BDSM desire, among other aspects of her personality. A treasure trove of both quantity and astonishing quality that, so far as we know, was never seen by anyone but the artist, until Schaefer’s death in 2008.

Schaefer’s possessions were tossed out or sold away after he died alone in his apartment at the age of sixty-seven. When the apartment’s contents of value — stereo, cameras, enlargers — were catalogued for sale, the estate liquidator held onto 14 boxes filled with Polaroids, sensing they might also be worth something. That he not only kept them but kept them together is an astounding moment of foresight and good fortune. This private archive came to the attention of San Francisco painter Andrew Masullo, who bought it all and in 2017 donated the whole lot to SFMOMA. A previously unknown oeuvre not just snatched from the jaws of oblivion, but now in an esteemed museum collection.

Within two years, curator Erin O’Toole has shaped both an important exhibition and an accompanying book, published by MACK, thoroughly illustrated with photos and with excellent short essays by O’Toole, New Yorker writer Hilton Als, and artist, LGBTQ activist, and Transparent producer Zackary Drucker. The essays bring up many paradoxes of the show, such as: What are the ethics of publicly exhibiting the private photographs of a deceased artist? What pronoun is properly used here, he or she (the essay authors each make individual choices)? Is the artist Schaefer or April Dawn Alison (O’Toole convincingly argues for the feminine persona)? And Drucker considers April Dawn Alison’s possible desire for personal visibility versus the need to protect her personal safety, even in the Bay Area where there’s long been a vibrant queer community, but where in the ’70s and ’80s being a trans woman in public would certainly have been dangerous (and can still be). As Drucker writes, “Being seen is simultaneously vulnerable and empowering.”

It took months for O’Toole to sift through the April Dawn Alison archive. “The good news is that most of the pictures were made as part of larger shoots, rather than as single images, so I could analyze them in groups,” she told me via email. “As I was choosing the final cut I was thinking about aesthetics and storytelling, as you say, but also about recurring themes, chronology, and how to give a sense of the sheer variety of the various personas, scenarios, and poses. I wanted to represent the spirit of the entire archive and suggest its immense scale without overwhelming people with too many pictures.”

The result is a single room, lined with pictures in thematic groups where the viewer moves through the evolution and aging of April Dawn Alison over more than three decades. And however fabulous the whole backstory, in the end it’s the photographs themselves that are the vibrant the stars of the show.

There’s one very enlarged photo as you enter the gallery: April Dawn Alison in a fitted red sweater and sharp white skirt, a gold whistle around her neck, fistfuls of Polaroids in both hands. It’s an arresting image, all the more so at that scale, and I wondered if O’Toole wasn’t tempted to enlarge other images. “Personally, I love the intimacy of Polaroids,” she wrote back, “and I like that the small scale forces people to look closely and take their time as they move through the show.”

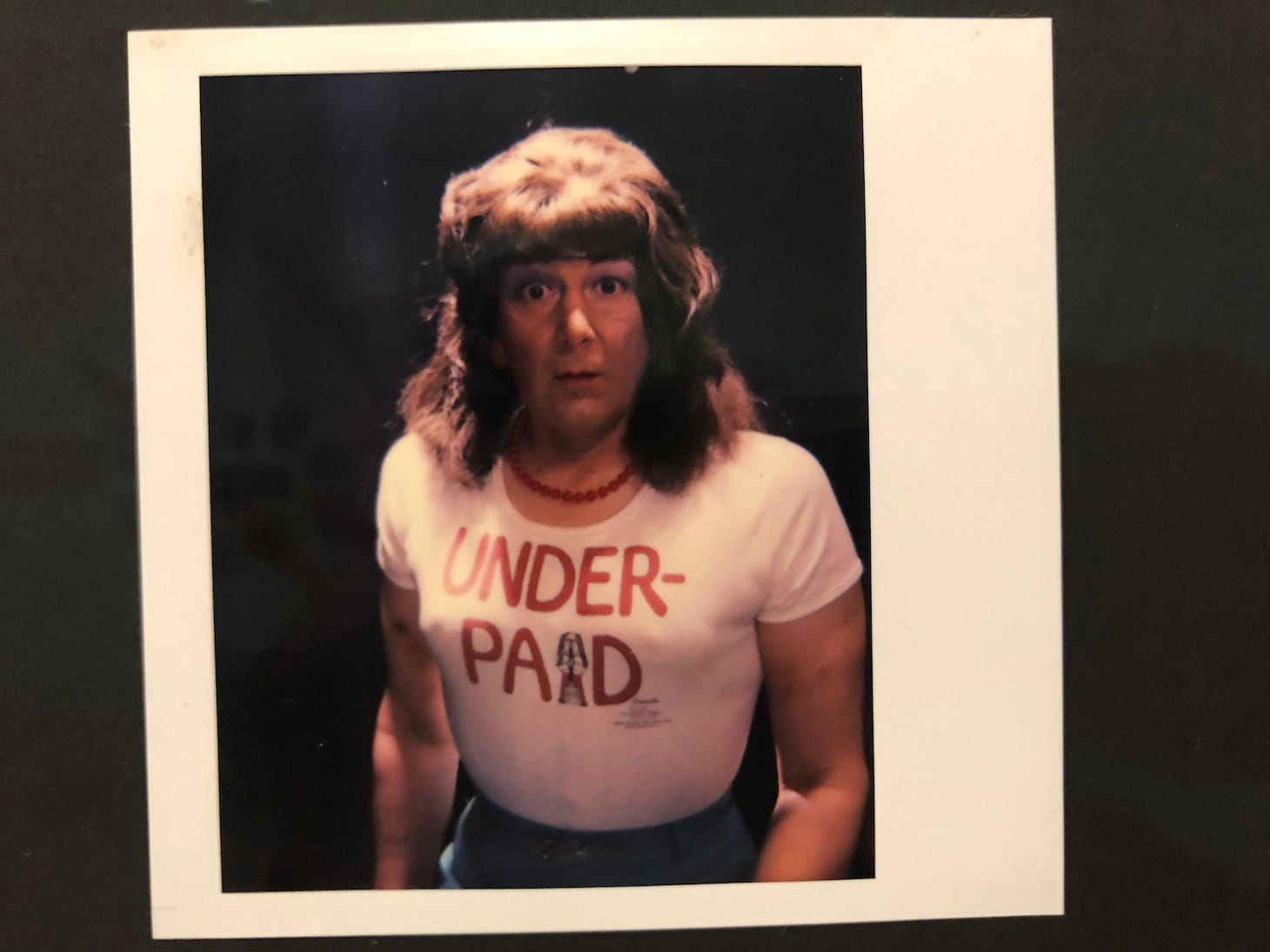

It’s true that I lingered a long time with each grouping, always finding new details — photographs on a back wall, the shimmer of blue eyeshadow, a jade plant on an outdoor balcony — that begged me to look further. And I couldn’t help but draw conclusions. Am I wrong to think April Dawn was a feminist? She esteems women’s work, posing while loading the dishwasher or alongside the vacuum cleaner. In one series she wears a tight white T-shirt bearing working-woman cartoon character Cathy standing in for the “I” of the message: UNDERPAID.

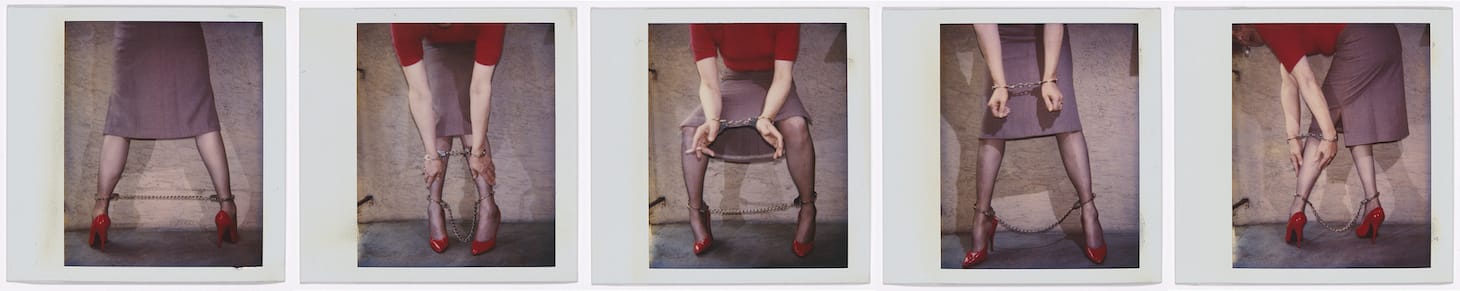

In a time of increasing LGBTQ activism and visibility, April Dawn Alison is wonderfully cheering — a beautiful time capsule of queer expression — but sometimes also quite sad. It’s impossible to look at her careful makeup and clever outfits and not feel sorry that maybe no one else got to appreciate her appearance in her lifetime. Though O’Toole has spoken with Schaefer’s relatives and many friends, she’s not so far found anyone who knew about April Dawn Alison, much less met her. That sense of loss is especially poignant in, for example, what looks to be a party scene, complete with balloons, where presumably there was just one guest. Or in the tableaux of BDSM where April Dawn Alison is trussed, gagged, hanging, but where there was (presumably) no partner in play. Which does beg the question, could she have tied herself up so effectively? Done it all herself, even where she hangs upside down above the kitchen sink?

I confess to feeling unsure the first time I walked through the April Dawn Alison show, wondering if it was OK to closely examine work that was kept private during its maker’s lifetime. But after spending time among the photographs, it’s impossible not to feel that three decades of carefully staged and produced self-portraits constitute, in O’Toole’s words, “a conceptual project.” Art, in other words. And art requires a viewer.

We might never have answers for all the questions this body of work raises. But we have what’s left to us here, which, for all its mystery, is quite a lot. We’re lucky to have it.

April Dawn Alison continues at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (151 3rd Street, San Francisco) through December 1. The exhibition is curated by Erin O’Toole.