R.I.P. Ric Ocasek, Icon of Blankness

Whenever the chugging intro to “Just What I Needed” or “My Best Friend’s Girl” plays, fans of adolescent drama pump their fists and say yeah.

Rest in peace, Ric Ocasek, the gawkiest new wave icon, the most repressed control freak, the strangest and most deadpan singer-songwriter to have crafted pop jewels. With the Cars, Ocasek wrote cheerful singalongs, impassive baubles, bewildering hooks, deceptively friendly formal paradoxes. There aren’t many tighter pop bands — their shiny coldness fascinates in its severity. He even wrote songs that approximate emotions, if you care for that sort of thing.

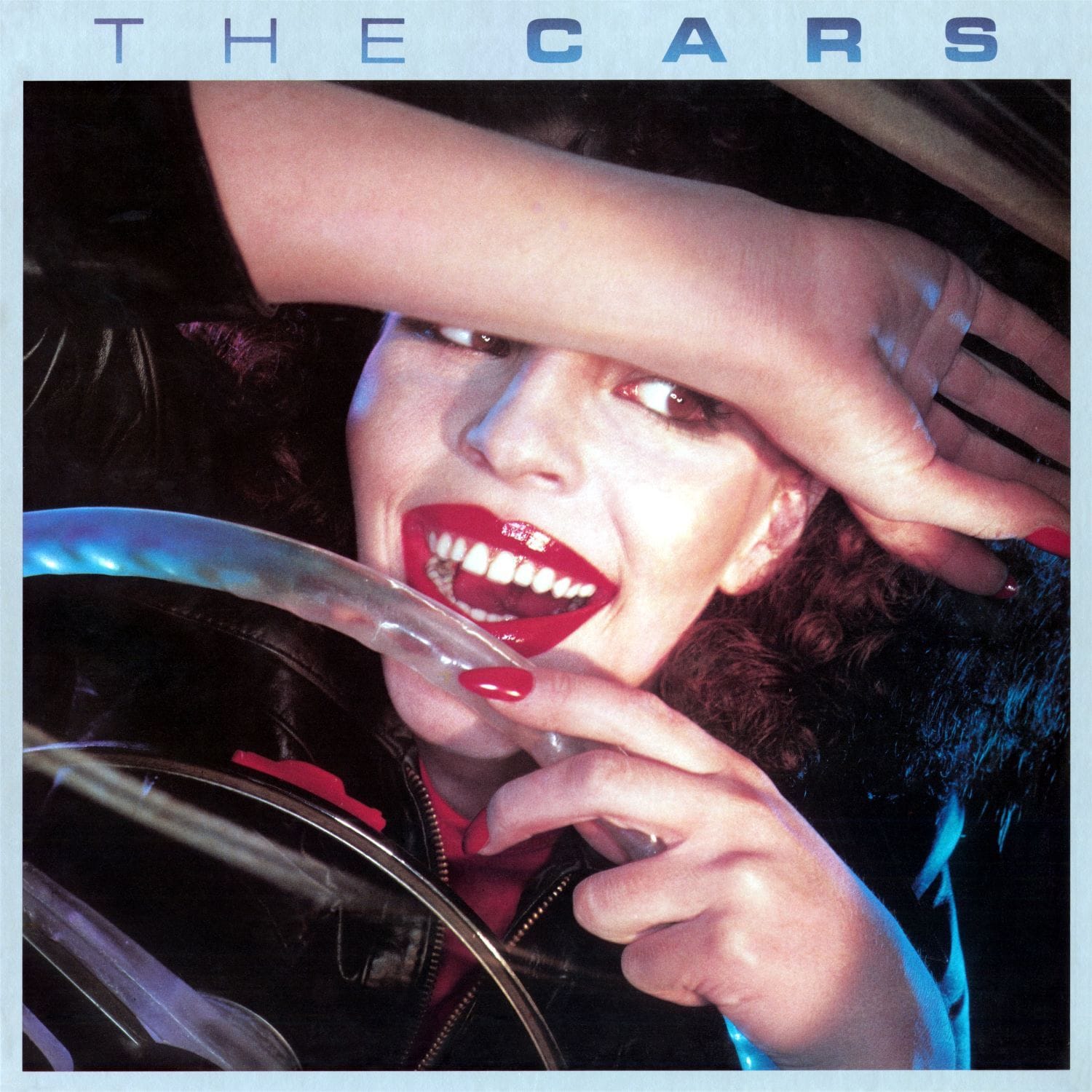

The various members of the Cars were rock veterans, having played in bar bands around Boston for years before coming together in the mid-‘70s. By the time their self-titled debut, The Cars (1978), came out, Ocasek and bassist-singer Benjamin Orr had been musical collaborators through a decade’s worth of stylistic permutations, searching for the most exactly detached pop genre, shedding acoustic folk and pub-rock guises before settling on their signature power-pop new-wave hybrid.

Of the two vocalists, Ocasek was the robot-voiced nerd, Orr the slick hunk (often his baritone sounds like he’s flexing in the mirror). Lead guitarist Elliot Easton and keyboardist Greg Hawkes soloed expertly and inscrutably over the steady thumping backbeat of drummer David Robinson, formerly of the Modern Lovers.

The Cars, their biggest seller, beloved among power-pop aficionados, applies arty synthesizer textures and knowing humor to what’s essentially traditional melodic ‘70s hard rock. It’s the rare album where the majority of the songs have endured as rock radio hits (even the nonsingles!). To this day, whenever the chugging intro to “Just What I Needed” or “My Best Friend’s Girl” plays, fans of adolescent drama pump their fists and say yeah.

“You’re All I’ve Got Tonight,” a hit nonsingle, is definitive: over a tightly wound, slowly building, vaguely menacing amalgam of snarling guitars and glittering synthesizers, Ocasek sneers an arch come-on. “I don’t care if you use me again, I don’t care if you abuse me again,” announces the nerd to someone who has probably done none of those things — there’s no indication the addressee is present or listening. If the song were sadder or quieter, the same lyrics would suggest a vulnerable confession; if the lyrics admitted desire rather than projecting it onto the other, it would sound like a hard-rock sex jam.

As it is, given the guitar swagger, this is the defensive condescension of someone afraid to sound lovelorn. The desperation is unmasked when the chorus hits and the refrain (“You’re all I’ve got tonight/I need you tonight”) is revealed as both pathetic and hilarious. “You can mock me, I don’t care,” insists Ocasek, but the imaginary lover will never mock him as much as those preening guitars do.

Through the disjunction between smoothly functional music and a dorky singer, “You’re All I’ve Got Tonight” typifies a classic new wave dynamic. It’s an anomaly in their catalogue: their subsequent music rarely so resembled conventionally expressive songwriting, rarely required attention to lyrical ironies, and never did they play so strictly by the conventions of ‘70s rock again.

Thanks to Roy Thomas Baker’s production, which daubs on the oohing multi-tracked harmonies endemic to power pop and pre-punk hard rock, their debut has a cheerfully corny quality — red-blooded American boys play new wave music!

“[T]hey have taken some important but disparate contemporary trends—punk minimalism, the labyrinthine synthesizer and guitar textures of art rock, the ‘50s rockabilly revival and the melodious terseness of power pop—and mixed them into a personal and appealing blend,” wrote Robert Palmer in The New York Times when they appeared at the Bottom Line in August 1978. The description is perfect in in the way it captures a certain queasy density: they really do cram all those ingredients onto the same album.

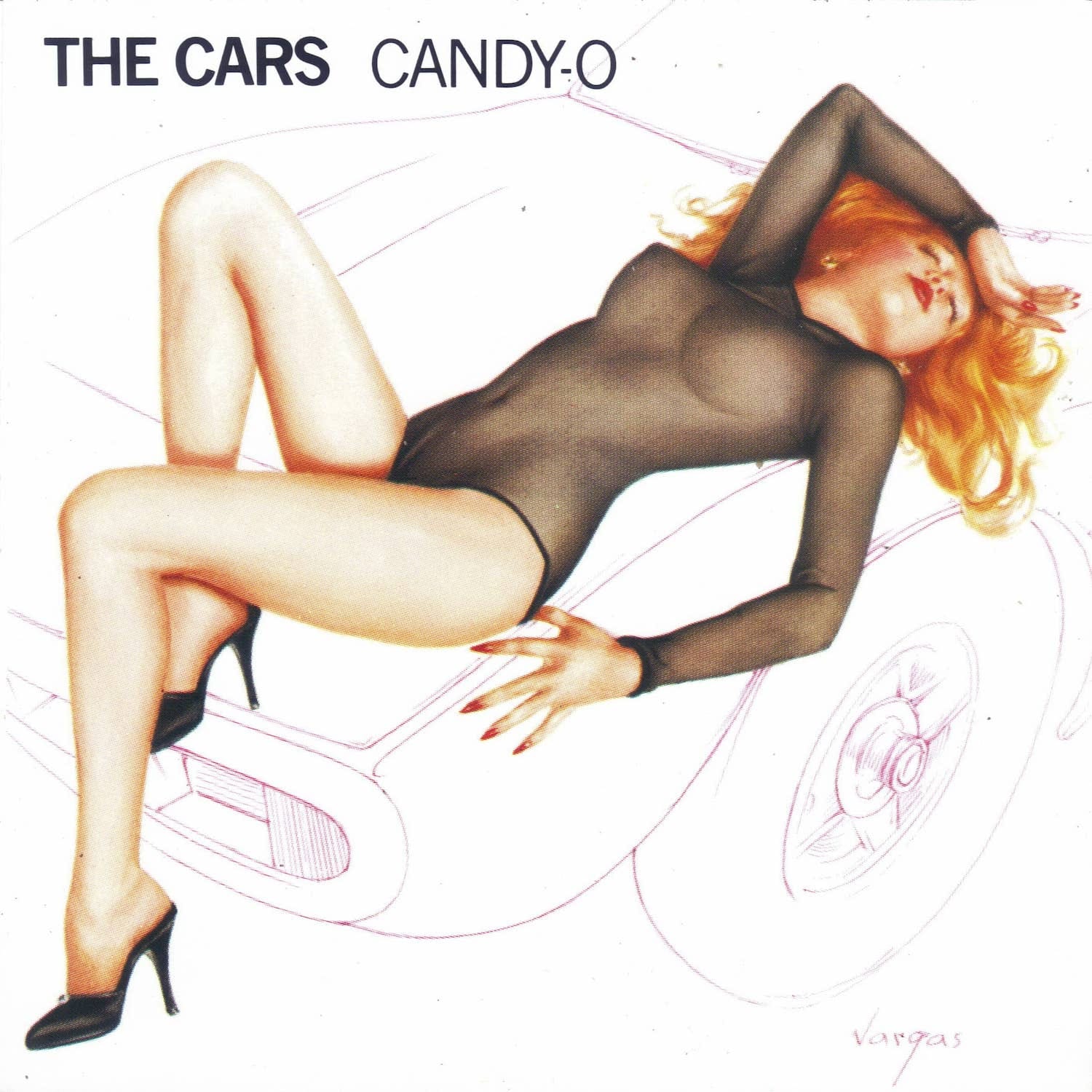

Nonetheless, The Cars defined a stark, unsettling sensibility, and their second album, Candy-O (1979), was the realization: it cuts the debut’s otiose elements (rockabilly, power pop’s wholesome cheer, overdubbed background singing) and leaves something sparer, scarier, more mechanical.

The leftover empty space reveals the extent to which their sharp angles gleam. In blankness lies excitement and distance. This is classic Cars — the world’s sleekest and coolest pop album. Candy-O soars and glides, extracting a control freak’s satisfaction from the precise interlockings of circular, metallic keyboards, blunt rhythm guitar, and barbed riffage that exist less to display technical skill or express feeling than to click into a shimmering, totally efficient musical machine. The album is as glassy, sinuous, and perplexing as a sex toy you don’t know how to use.

These songs contain more hooks than most bands will write in a career: the entwined bassline, aerobic synthesizers, skeletal percussion, and precisely timed handclaps (clap clap! clap clap clap! clap clap clap clap! clap clap!) in “Let’s Go”; the three or four separate keyboards in “Night Spots,” twisting about in patterns too complex to unravel; or the jerky, dinky bounce of “Lust for Kicks,” which cycles playfully through a set of reflexive key changes. (Rap beats with key changes, like Rae Sremmurd’s “Powerglide” or Kasher Quon & Teejayx6’s “Dynamic Duo,” display the same delight in automated patterns.)

The lyrics are there if you want them, but they’re not included for communication’s sake, or even to establish tension with the music; they function as decoration. Bits of language like “Alienation is the craze,” “They wanna crack your crossword smile,” and “Shoo be doo” establish the appropriate aura of sex and danger. But Ocasek isn’t fooling anybody: the album’s real romance lies between form and abstraction.

Candy-O wouldn’t sound so cold and detached if not for the pop context, the superficial cheer. One doesn’t marvel over the impersonality of industrial or ambient music, because those aren’t supposed to be expressive forms. The songs on Candy-O quiver with subdued alarm, a nagging feeling that something substantive has been excised, but you can’t place what.

By obsessively refining a polished compendium of knotted genre conventions at the expense of feeling, the Cars both apotheosize and violate popform: direct emotion is also a genre convention, the only one omitted. Their pop formalism lands with a crisp minimalist shock: they are pointedly, aggressively impersonal, which is how you know real people are involved.

Panorama (1980) wasn’t as big a hit, critically dismissed as art-rock, but in retrospect their third album’s dark guitar sound and robotic hooks play as unadulterated new wave. Their increasingly jagged edges make the music stiffer and starker, yet the electronic polish is retained; sound effects like the garbled robot voices on “Panorama” and the cascading sirens that explode in the middle of “Getting Through” fit right in. “Misfit Kid” is a marvelously incoherent attempt at social commentary, as slithering keyboards and echoey drumclaps create a shimmering, ominous electronic surface. “I’m the American misfit kid/I’m still wondering what I did,” muses Ocasek. “I get rhythm, I get cornflakes/I get fast love, I get wasted yeah.” Brilliant!

Shake It Up (1981) is jauntier and more frivolous, abounding with bouncy dance tracks (“Shake It Up”); exquisite exercises in gilded melancholy (“Since You’re Gone”); and gushing synth breakdowns that sparkle and fray (“I’m Not the One”). On “Cruiser” the band attempts to write a loud, rockin’ riff, yet even this sounds automated; intricately woven around the bleepy keyboard hook and the floaty background harmonies, the song zooms. A detached approximation of rock energy that winds up more definitive than the original model is also a hallmark of classic Cars. When the song unravels in a tangle of guitars and wires, it feels as satisfying as solving a puzzle.

Those albums are the Cars’ achievement. Ocasek was also renowned as a producer, having collaborated over the years with a number of artier underground bands (Suicide, Romeo Void, Bad Brains, Guided By Voices, Le Tigre, Brazilian Girls) — whose eccentricities the Cars shared, albeit in more sublimated ways — as well as other pop bands (Weezer, No Doubt).

He scored solo hits, too; his goofy, robotic solo debut Beatitude (1982), in particular, is weirder and tighter than the Cars’ subsequent music, which flirted with ‘80s pop styles without fully committing. Heartbeat City (1984) was a commercial comeback, with five Top 40 singles, but the flushed, percolating electronic sound didn’t mesh with their sensibility (except on the aching hit ballad “Drive”), and Door to Door (1987) could have been a pop metal album if only they’d turned up the guitars.

Straightforward discographical exposition suits the Cars because they specialized in fine distinctions and subtle advances. This was not a band that made discrete statements; they didn’t fit the critical ideal of clear progress from album to album. They had a serviceable formula, and they adjusted it precisely.

Critical appreciations of new wave tend to stress how strict aesthetic distance creates feeling through inversion — how emotions can be more affecting when presented with detachment — which is true of the Cars: the mock desperation of “Dangerous Type,” or the amused infatuation of “You Wear Those Eyes,” qualify as appropriately subverted pop ironies.

But there’s also a sense in which the Cars negate that whole critical tradition. Most comparable bands — Roxy Music, Pet Shop Boys — use blankness as one ingredient in a more complex synthesis, a yardstick by which to measure desire and absurdity. For the Cars, blankness — repression — is the sum of their art, lacking the human qualities to balance the equation.

Of their contemporaries, the only pop band I know whose modest, workaday formalism matches theirs is New Order. Like the Cars, New Order depends on the contrast between the beautifully functional and efficient music and dorky singing; but Bernard Sumner’s vocals are so endearing that the result is paradoxically expressive, vulnerable, deeply felt. By contrast, the Cars are pure consumer object: shiny, inexpressive, chilling. There’s no equivalent endearing ingredient in most of their music, and so their detachment remains total.

Yet their sound, while devoid of feeling, does not lack disjunctions or textual weirdnesses. Candy-O and Panorama fascinate partially because their effort-to-content ratio is so skewed; by the standards of empty pop product, these albums are quite intricate. If there’s no emotion invested in the performance, why bother with such precision? Why strain to align the drums and bassline on “Double Life” so exactly? Why must the guitar solo on “It’s All I Can Do” complement the synthesizer in perfect harmony?

These songs suggest that the need for exactitude parallels the need for affectlessness. But what’s behind this compulsion? Why should pop music even exist, if not to communicate? The surreal drive to put so much work into something so trivial produces a gripping dissonance — and, to my ears, an endless delight.

Sometimes we want a totally inexpressive band, after all. Human virtues are often imposed on us in unwelcome ways, and it’s nice to escape for a while. Sometimes we want to dance to rhythms that are jokes about repression.

Some bands make statements; the Cars delineated a sensibility. If the sensibility resonates, they did their job. Rest in peace, Ric Ocasek.