Eileen Gray, an Architect Ahead of Her Time, Reclaims the Spotlight

By every measure, Eileen Gray ought to be as well-known as her Modernist male contemporaries. An exhibition at Bard’s Graduate Center offers a smart correction to the historical record.

Between 1926-1929, Irish architect and modernist Eileen Gray designed and built E 1027 — a white, angular villa in France’s Roquebrune-Cap-Martin on the Côte d’Azur. The villa was Gray’s first major architectural work and she designed it to be a living space that integrated her artistic vision both inside and out — from her distinctive furniture designs to the villa’s floor-to-ceiling windows and sunken solarium. The design of E 1027 prized movement, light, and efficiency; every part of every room served a purpose to Gray. There was no “wasted” space. Already a well-known furniture designer, Gray was one of the pioneering architect-designers of what would come to be known as the International Style.

By every measure, Eileen Gray ought to be as well-known as her male contemporaries, if not more so, as E 1027 was the first Modernist building completed by a female architect. However, the story of E 1027 — and what happened to it during the twentieth century — has cast an oversized shadow across Gray’s broader biography. The current Eileen Gray exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery offers a smart, nuanced counterbalance to the classic sort of E 1027-centric history that has largely obscured her extensive, complex oeuvre.

Gray studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London from 1900-1902. Captivated by the 1900 L’Exposition Universelle, she moved to Paris in 1903 to attend courses at Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi where lacquer became her preferred métier, both professionally and personally. (Gray, who was bisexual, would reportedly drive around Paris in a convertible with one of her lovers, the nightclub singer Damia, with Damia’s pet panther in the backseat. Gray’s family’s wealth also ensured both her education and independence.) She and artist Seizo Sugawara opened a lacquer workshop in 1910, in addition to the weaving workshop she set up with another artist, Evelyn Wyld. In 1914, Gray even became one of the first women in Paris to get a driver’s license and drove an ambulance during World War I.

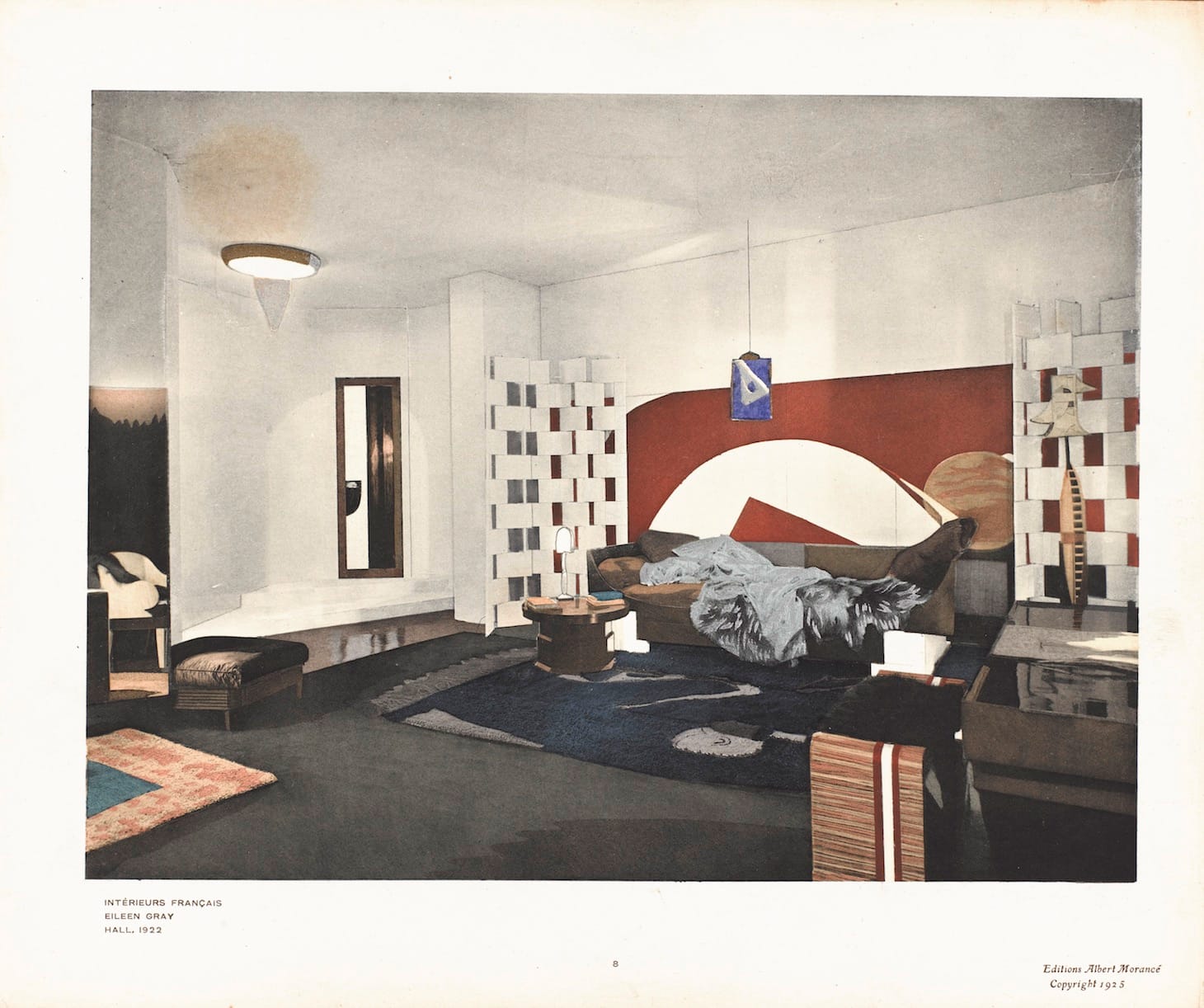

Gray undertook her first interior project in 1919 — an apartment for society maven Juliette Lévy — full of lacquered block screens, exotic light fixtures, and the famous (if a bit fetishizing) “Dragons” armchair. The photographs, schematics, and journal sketches featured in Eileen Gray — many of which have never been publicly exhibited before — demonstrate how her style and expertise built up through the decades of the early twentieth century. Under the male pseudonym Jean Désert, Gray opened her own gallery in 1922, the clientele of which would quickly come to include Ezra Pound, James Joyce, and the Rothchilds. Her work with E 1027 marked her first foray into architecture (completed when she was 51) with the encouragement of her then-lover, the Romanian-born architect and L’Architecture Vivante editor Jean Badovici.

The villa’s enigmatic name is a numerological reference to Gray and Badovici and its symbolism has become a significant part of the villa’s contemporary mythos. (E is for Eileen; 10, 2, and 7 correspond to Badovici’s and Gray’s initials, intertwined with each other.) Two particularly iconic pieces of Gray’s furniture from the house include a lightweight tubular side table (designed so her sister could have breakfast in bed), and the Transat deck chairs. When the villa was completed, L’Architecture Vivante devoted an entire issue to it. “Even the furnishings should lose their individuality by blending in with the architectural ensemble,” Gray wrote in the 1929 issue, and from images it’s clear that E 1027 embodied that ethos.

When Badovici and Gray separated in 1932, she left E 1027 to him and began construction on a new villa (“Tempe à Pailla”) in the adjacent French town, Menton. In the early 1930s, E 1027 caught the attention of the well-known Swiss-French architect and artist, Le Corbusier, a friend and frequent guest of Badovici’s, and in the ensuing decades it became impossible to sort out the credit of E 1027 as the men began implicitly and explicitly writing Gray out of the E 1027 story.

Often described as jealous of Gray’s talent — and unwilling to accept that a woman could design something as brilliant and thought-provoking as E 1027 — Le Corbusier painted eight cubist murals on the villa’s walls in the late 1930s, ensuring that his name is invariably linked to the history of villa. Further, he painted them while nude, an act that Gray, and many later historians, have taken as an assault on the villa. As Michael Watts outlines in The Economist, “The house has played a big part in Gray’s story, thanks to an episode that has become the focus of books, essays, documentaries, a novel and even a course on the sexual politics of architecture.” E 1027 is a brilliant example of pioneering architecture and it is unfortunate that Gray’s biography is inevitably defined by Le Corbusier. Aptly, Bard’s Eileen Gray relegates Le Corbusier to a historical footnote.

Although Bard’s gallery is currently closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it offers a fantastic online compilation of the exhibition’s themes, and thus Gray’s career. Comprising over 200 works — including furniture, lacquer, architectural drawings, photographs, notes, portfolios, and archival materials — the online version also features in-depth discussions of a subset of these items, contextualizing them within Gray’s oeuvre. A Transat chair, a rocket lamp, lacquer screens, and a stepstool towel rack (to name a few) all become the subjects of discussion among curators, gallery educators, and teen scholars.

From her early textiles and lacquers to her armchairs and architecture, Gray’s overall design aesthetic emphasizes geometry and continuity in form and materials. Object-centered histories — and Bard’s approach more generally — accentuate Gray’s more holistic approach to design. Almost a century after their original design, her emphasis on facilitating harmony between people and objects remains timeless.

Eileen Gray continues online indefinitely via the Bard Graduate Center gallery. The physical exhibition (18 West 86th Street, Upper East Side, Manhattan) was curated by Cloé Pitiot and is temporarily closed due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Upon reopening, the exhibition is scheduled to remain on view through October 28, though visitors should check the gallery’s website for updates.