The Evolving Designs of US Voting Ballots

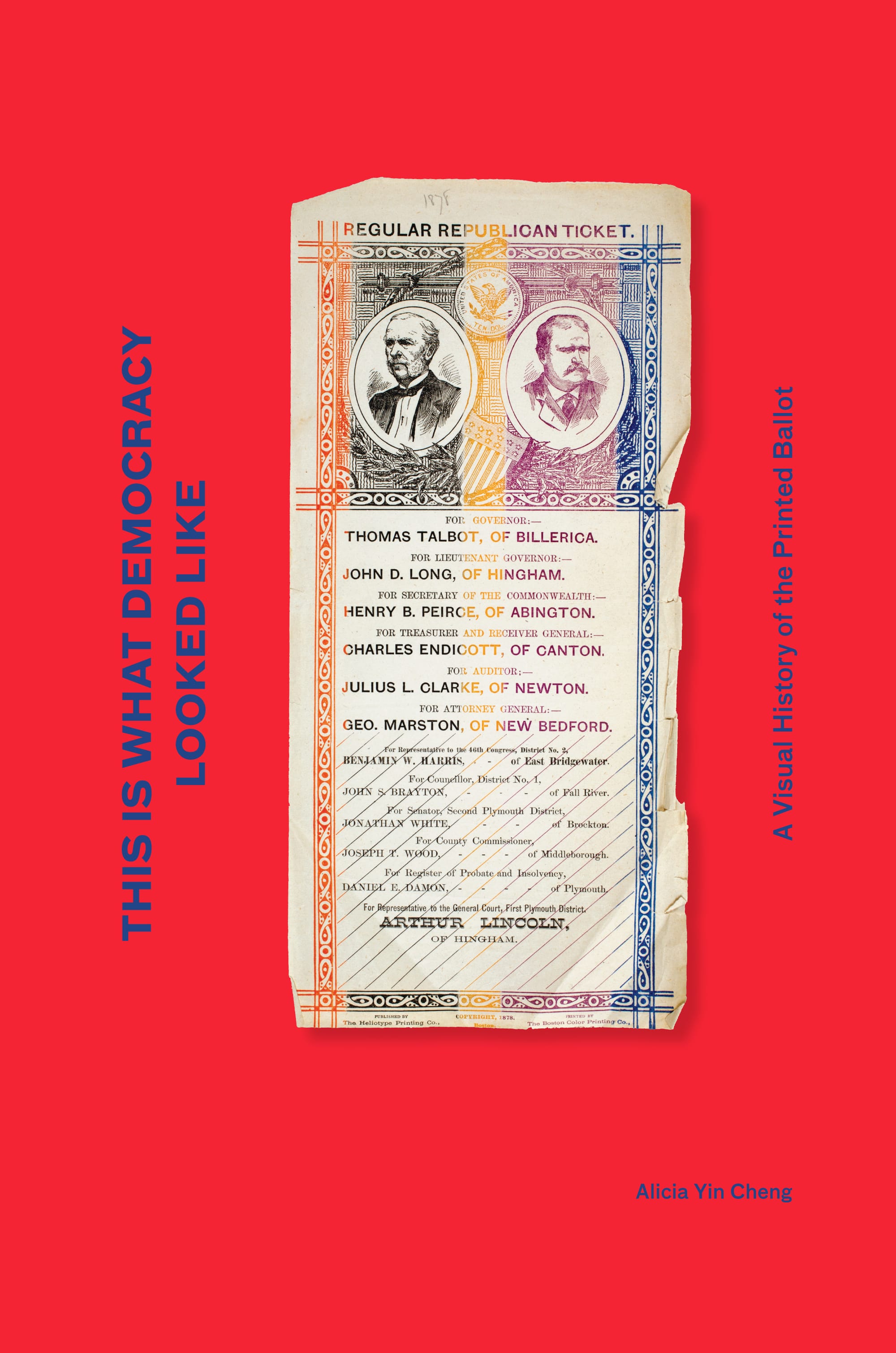

This Is What Democracy Looked Like by Alicia Yin Cheng is the first book of its kind to look at the history of ballot design.

Back in 2008, graphic designer Alicia Yin Cheng read a Jill Lepore article in the New Yorker about how Americans used to vote. A line about the ballots being colorful and public caught Cheng’s attention. Lepore, a historian at Harvard University, made time to meet with her, and Cheng considered writing a history of ballot design, but the project got pushed off.

After Donald Trump got elected president, Cheng revisited the idea and wrote the first book of its kind, This Is What Democracy Looked Like: A Visual History of the Printed Ballot, which was published this summer by Princeton Architectural Press.

“After the 2016 election, I was reeling,” Cheng said over the phone. “I took refuge in the idea that surely our republic has survived worse.”

In the book, Cheng explores the history of the physical and material act of voting. Before paper ballots, people used the viva voce system, rooted in ancient Greece, where voters announced their candidate to a clerk. In some US colonies, voters would use objects, like corn and beans, to vote yea or nay; and in other states, people would line up on opposite sides of a road to signal how they were voting.

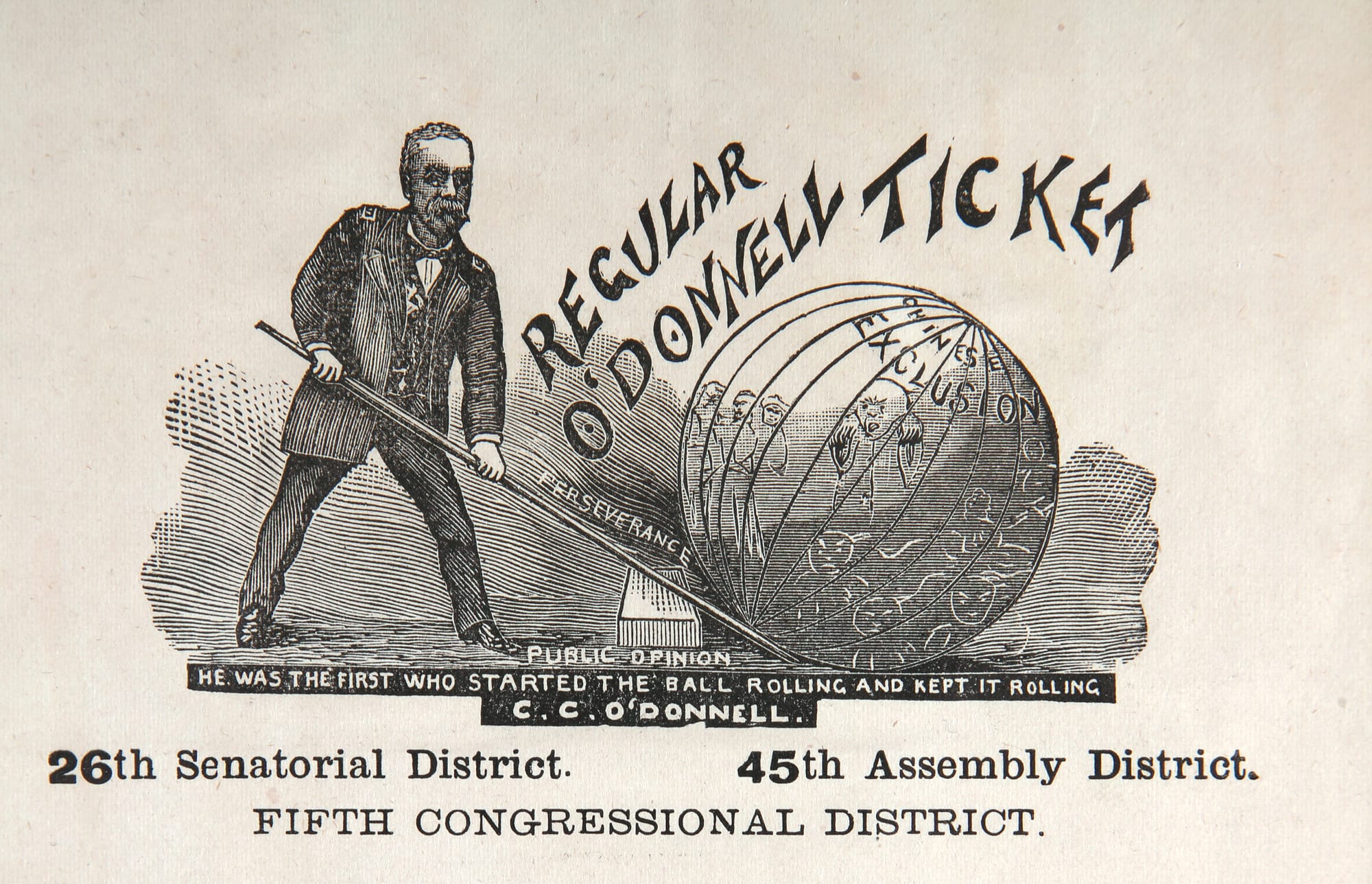

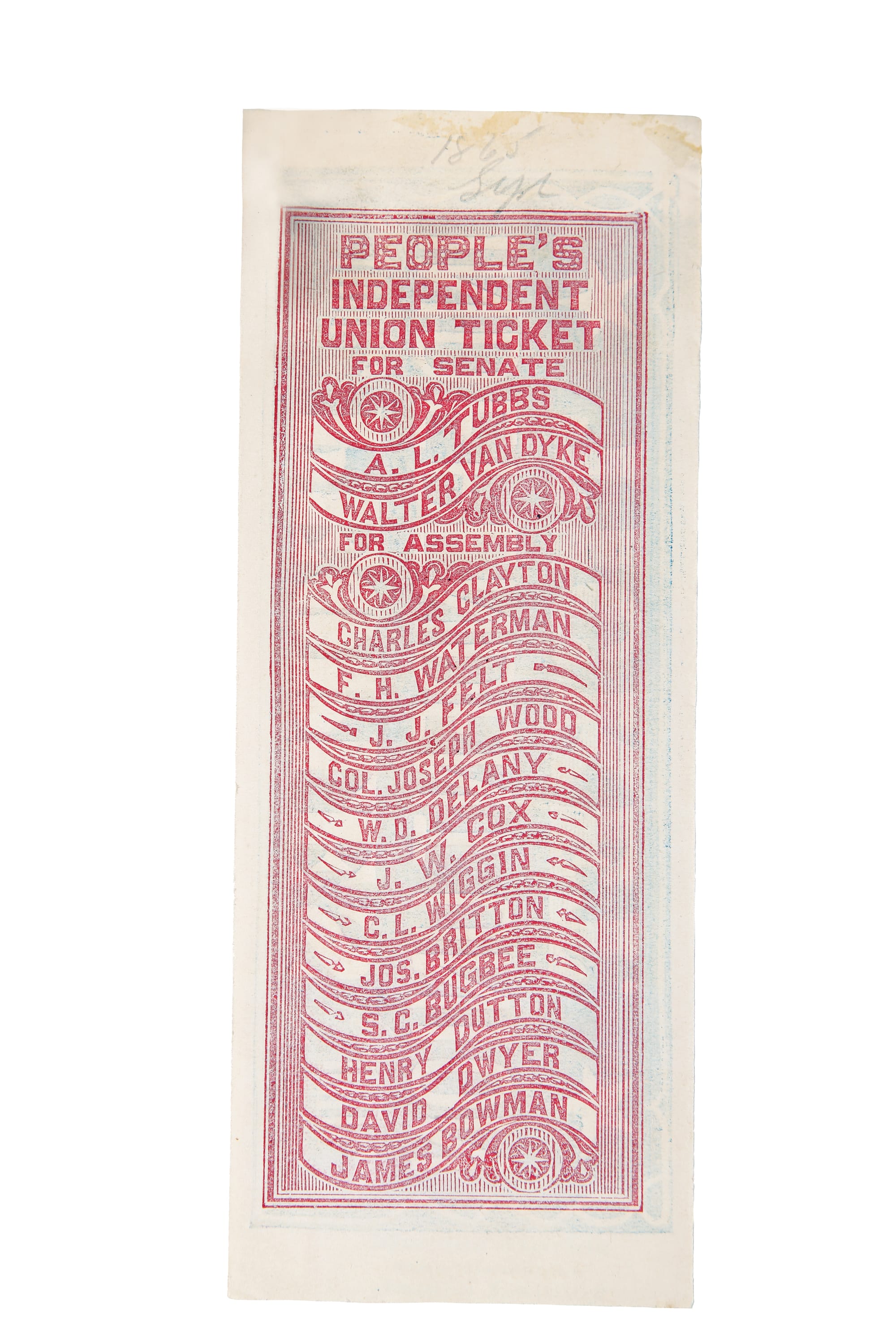

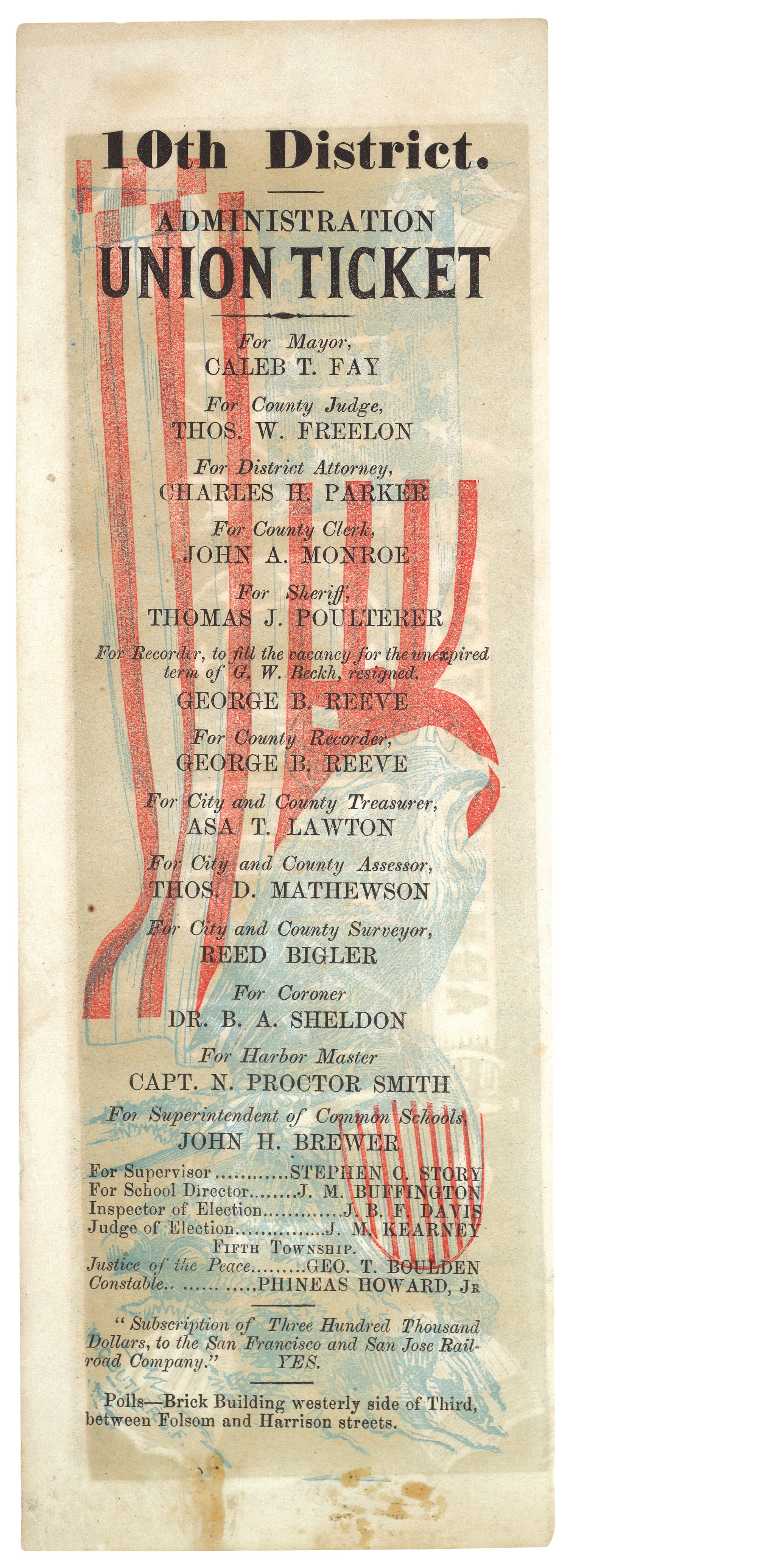

In the early days of the paper ballot, at the start of the 1800s, each municipality had its own requirements, which were not systematically enforced. Early ballots were slips with just one name or handwritten. Voting was an open system, and in some places, party workers solicited voters, handing out “straight party” tickets, which could be put in ballot boxes with no selections made. Cheng found blatantly racist and anti-immigration ballots, such as one in 1876, in San Francisco, where candidate Dr. C. C. O’Donnell pledged to deport all Chinese immigrants within 24 hours of taking office. Cheng describes the lettering used on this ballot as “early Chopsticks.” Printed ballots were required to be destroyed, so these examples shouldn’t really exist at all, Cheng says, quoting one collector who described them as “the most fugitive ephemera.”

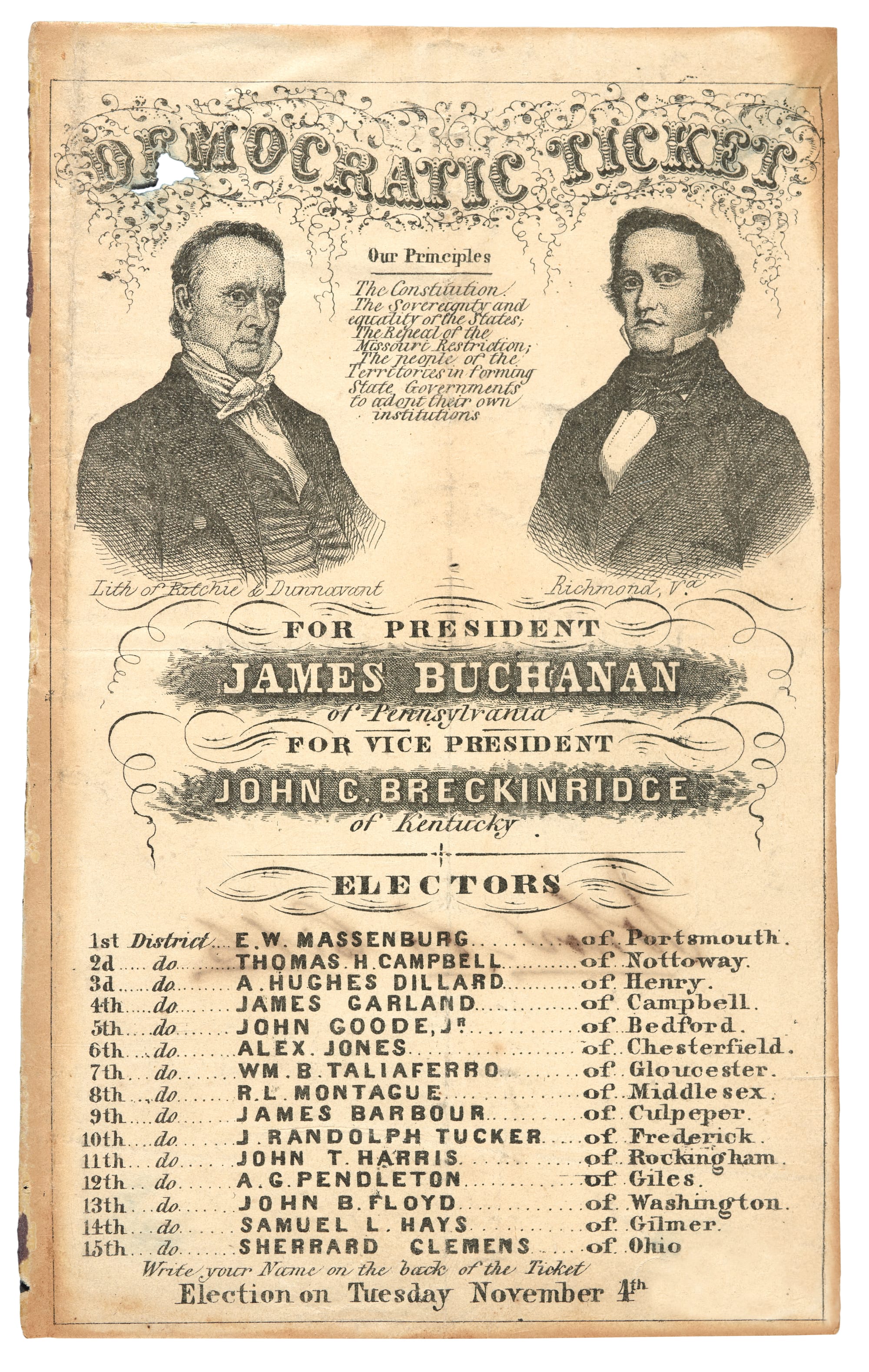

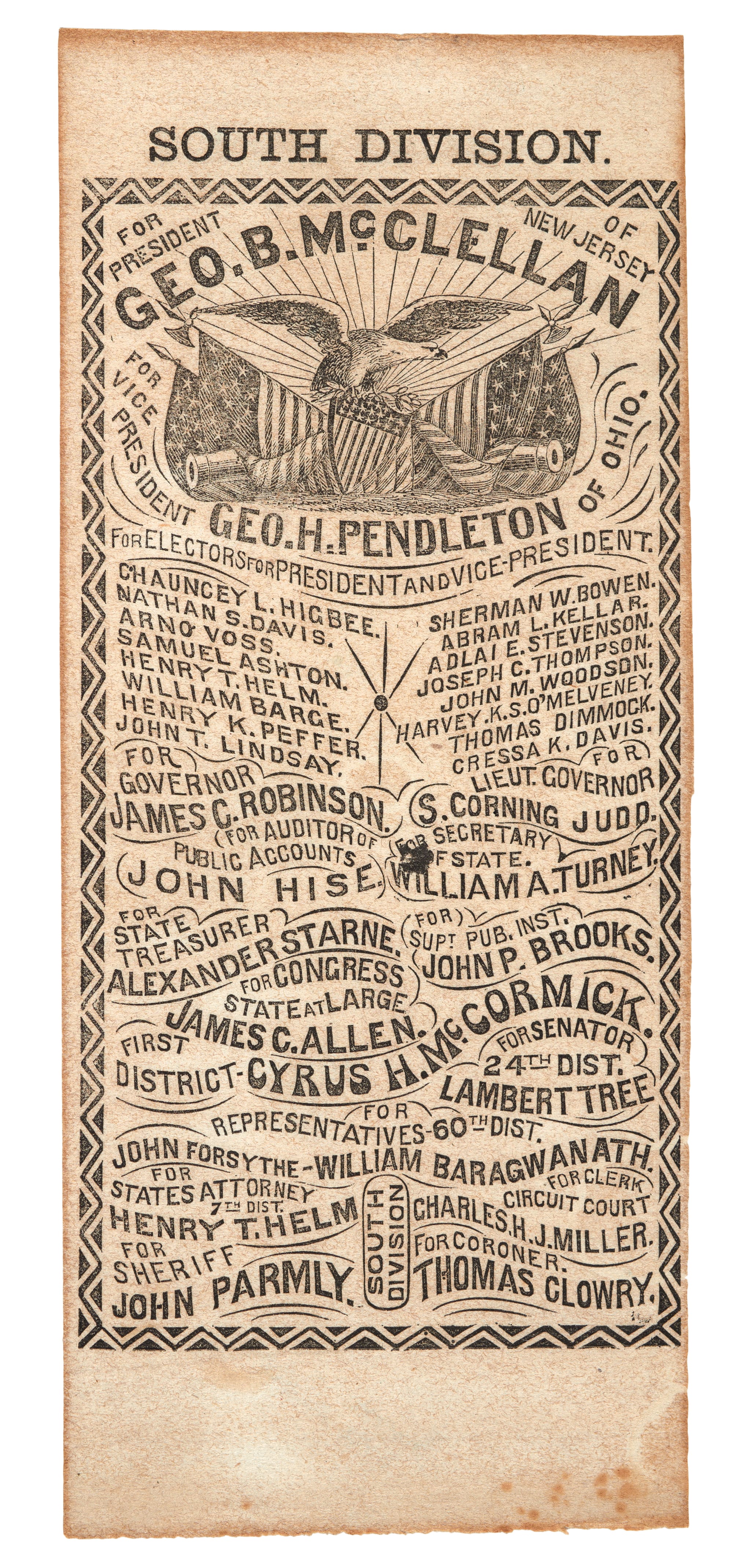

Cheng notes that between 1800 and 1850, the population of the US grew from 5.3 million to 23 million with immigrants arriving from Europe. Voting rights expanded as the requirements to own property were eased. But the design of the ballot reflects how some were included while others were not. For example, in the 1830s, the ornate typography and elaborate styles may have been meant to mislead voters who weren’t paying careful attention. Cheng writes that the volume of campaign material made regulation difficult, effectively leaving the parties in charge, or “the party foxes in charge of the electoral henhouse.”

Doing her research, Cheng realized that she needed to take into account all that was happening in the country. By 1856, she writes, all of the 34 states at the time had adopted universal suffrage for white males. In the decades that followed, the population expanded almost fourfold; the country underwent a civil war, followed by the end of slavery; and millions more of immigrants from China and all over the world continued to arrive.

“There’s this interrelationship and complexity and there’s so much about what’s going on in the world that influences the ballot,” she said. “You can’t just take the ballot in isolation.”

As a graphic designer, not a historian, Cheng says she felt free to look for the ballots that were most interesting to her. She found ones marked with images of roosters, a Dr. Seuss-like tree, and a ship to stand in for political parties — which grew to a large array in the early to mid-19th century, including the Liberal and Regular Democrats and Republicans, the Free Soil Party, the Citizens Party, the Labor Reform Party, and the Greenback Party. Cheng also found “pasters,” or gummed slips, handed out at the polls to write in an alternative candidate, and ballots with elaborate and colorful designs on the back to make them more attractive, as well as making it easier for party bosses to tell from the designs how people were voting.

Cheng loved the process of researching the book.

“I started out at the Huntington Library, which is just heaven. You apply for reading privileges, and I was given 10 boxes and that just blew my mind holding those artifacts — it compacted time in a way,” she said. “It was sort of like a treasure hunt where you don’t know what the treasure is.”

Cheng found all sorts of voter fraud. There was William “Boss” Tweed, head of Tammany Hall in New York, who had a boss serving as a vote gatherer in individual wards in New York. In his 1877 testimony to the New York Board of Aldermen, which Cheng describes as “chilling,” Tweed explained how he corrupted democracy. When asked if the ballots made the results he determined beforehand, Tweed responded, “The ballots made no result; the counters made the result.”

Fraud wasn’t limited to cities. In frontier settlements, people often voted at taverns, where they could exchange their votes for cash or whiskey. Another technique, voting “by whiskers,” meant a man would start the day voting with a full beard, then go back with sideburns and a moustache, then just the moustache, and, if needed, he could vote one more time clean shaven.

In the 1880s, the United States grew interested in the Australian model, which Cheng writes had conditions we take for granted today — it was secret and distributed by the government, rather than by political parties, and it listed candidates by the office they were running for, not their party affiliation. This helped end voting multiple times with different facial hair, but it kept certain voters disenfranchised with requirements that were forms of voter suppression, such as New York City voters needing to register in person on a Jewish holiday.

In the Progressive Era of the late 19th and early 20th century, with inventions like the car, the telephones, and the steam engine, many states grew interested in having voting machines rather than printed ballots. But machines didn’t magically solve all problems with counting votes, as the Florida election of 2000 with its “hanging chads” shows. That led to a Supreme Court case, Bush v. Gore, and George Bush becoming president.

The ballot is an artifact that touches on many broader issues, Cheng says.

“There’s this crazy Venn diagram of voter suppression and systemic racism and the history of suffrage,” she said. “The ballot is at the nexus of that.”

This is What Democracy Looked Like: A Visual History of the Printed Ballot by Alicia Yin Cheng is published by Princeton Architectural Press and is available at your favorite indie bookstore.