Computer-Generated New Yorker Cartoons Are Delightfully Weird

The palimpsestic drawings and irreverent captions dissolve into senselessness, upending the ubiquitous cartoon medium.

New Yorker cartoons are inextricably woven into the fabric of American visual culture. With an instantly recognizable formula — usually, a black-and-white drawing of an imagined scenario followed by a quippy caption in sleek Caslon Pro Italic — the daily gags are delightful satires of our shared human experience, riffing on everything from cats and produce shopping to climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic. The New Yorker's famous Cartoon Caption Contest, which asks readers to submit their wittiest one-liners, gets an average 5,732 entries each week, and the magazine receives thousands of drawings every month from hopeful artists.

What if a computer tried its hand at the iconic comics?

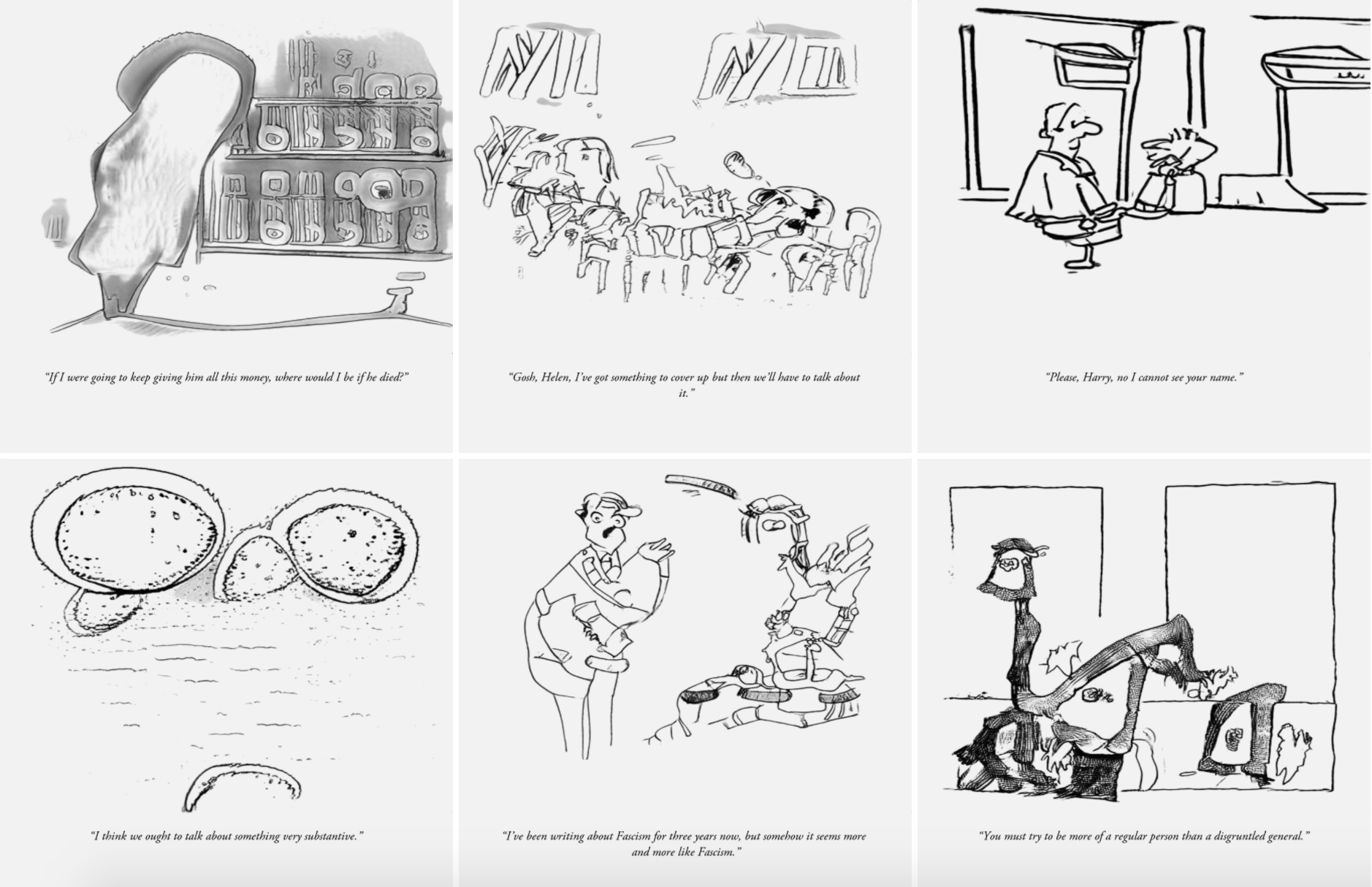

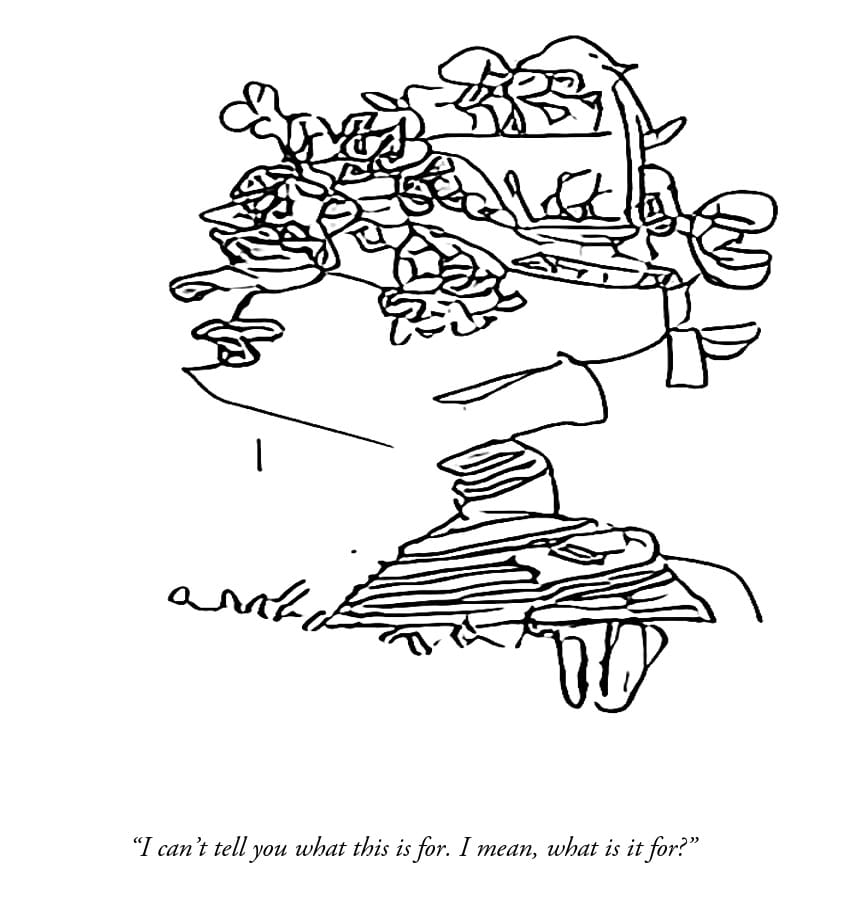

Playing on their ubiquity and familiarity,comics artist Ilan Manouach and AI engineer Ioannis Siglidis developed the Neural Yorker, an artificial intelligence (AI) engine that posts computer-generated cartoons on Twitter.The project consists of image-and-caption combinations produced by a generative adversarial network (GAN), a deep-learning-based model. The network is trained using a database ofpunchlines and images of cartoons found online and then "learns" to create new gags in the New Yorker's iconic style, with hilarious (and sometimes unsettling) results.

Whether it be Gary Larson's famous comic strips or "the cartoons of a small regional press from an unknown artist,"Manouach and Siglidis said, "the cartoon format thrives on quirkiness, absurdity, arbitrariness and cheap artifice in order to get their simple message through."

"Cartooning is paradoxically a 21st-century art form catering to a readership with limited attention for a quick visual gratification fix," Manouach and Siglidis told Hyperallergic. "The Neural Yorker explores the limits of an important feature in the history and the modes of address of cartoon making: the non sequitur."

At a cursory glance, the AI-generated panels evoke your everyday New Yorker joke. But a closer look reveals strange anomalies:two businessmen are seated at a table, but their figures are warped and distorted, and one of them lacks a human face. The contour lines are unfinished and the composition is oddly irrational, like a palimpsest or an Escherian stairwell.Add an inane caption — "Are there any stupid people here that don't need a little paint?" — and the whole thing collapses into senselessness.

The Neural Yorker jokes may not spark vocal laughter or a knowing smile, like real New Yorker gags do, but they have their own comic effect: a feeling of self-aware ridiculousness, like looking at oneself in the mirror wearing a silly hat.Manouach andSiglidis's project plumbs the construct of the cartoon format, forcing the medium to look inward and highlighting the subjectivity of humor. As formerNew Yorker editor Bob Mankoff said in the 2015 documentary Very Semi-Serious: “Cartoons either make the strange familiar or the familiar strange.”

Manouach, who describes himself as a "conceptual comic book artist," has made a career of reimagining the cartoon tradition — in 2016, Hyperallergic covered his tactile graphic novel for visually impaired readers; currently, he is co-editing a glossary on artificial intelligence and working on Fastwalkers, a manga comic book written with emergent AI. Among his first forays into AI with Siglidis, who is starting a PhD on Deep Learning and Computer Vision at the École des Ponts ParisTech, was behind @RadicalDumb, a satirical text generator trained on transcripts from stand-up comedians and Tweets from alt-righters.

"When we started making bots, we were thrilled by their modeling power, by the way they could learn to reproduce concepts or a tone as complicated as humor orirony, produced by a set of independent data-points, and with little prior knowledge about the world," Manouach andSiglidis told Hyperallergic.

"When we can now read something written on Twitter or even in the street that resembles the output of our bots, we experience something close to a serendipity."